The U.S. has few bright spots when accounting for global trade: we import much more than we export. Entertainment is America’s #1 export. After that, medical innovation shines.

The U.S. has few bright spots when accounting for global trade: we import much more than we export. Entertainment is America’s #1 export. After that, medical innovation shines.

But the window on that lead is closing. 92% of Americans believe it’s important for the U.S. to be the global leader in medical innovation and research. And, most Americans believe the U.S. has been in a strong position in medical innovation, research and development, and technical innovation, especially for new cures and treatments for patients, and medical innovations that create jobs and drive economic growth; but a weakening position in science, technology, engineering and math education threatens U.S. dominance in medical innovation.

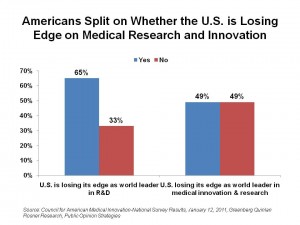

Two-thirds of Americans see the U.S. losing its edge as the world leader in medical R&D, as shown in the chart based on data from a survey sponsored by the Council for American Medical Innovation (CAMI). This edge is “Ours To Lose,” which is the title of CAMI’s survey report.

72% of Americans see significant long-term negative impact on Americans’ quality of life, employment and economic growth if the U.S. fails to spend more on medical innovation and research. Furthermore, most Americans polled believe that medical innovation lowers health care costs.

The survey was conducted by Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research with Public Opinion Strategies on behalf of CAMI in January 2011 among 1,009 adults age 18 and over.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: “When you think about it, medical innovation can best be characterized as a human and economic value proposition that our nation simply cannot turn down,” said Mike Leavitt, former Utah Governor, former U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services and current Co-Chair of CAMI. “In short, value for our economy, for our competitiveness, for our ability to create jobs, and above all, for our long-term health and wellness. The more we work together to make this issue a national priority today, the stronger our nation will be 5, 10 and 15 years from now. If we rise to the occasion now, the dividends, both economic and human, will be paid in multiples for years to come.”

Health Populi’s Hot Points: “When you think about it, medical innovation can best be characterized as a human and economic value proposition that our nation simply cannot turn down,” said Mike Leavitt, former Utah Governor, former U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services and current Co-Chair of CAMI. “In short, value for our economy, for our competitiveness, for our ability to create jobs, and above all, for our long-term health and wellness. The more we work together to make this issue a national priority today, the stronger our nation will be 5, 10 and 15 years from now. If we rise to the occasion now, the dividends, both economic and human, will be paid in multiples for years to come.”

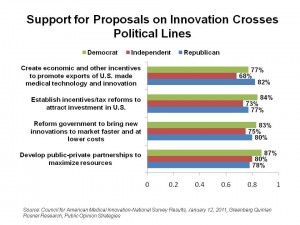

As Mike Leavitt points out, “working together” will be key to re-invigorate medical innovation in the U.S. So it’s encouraging to see that health citizens across political parties support various strategies for supporting medical innovation in America. The chart illustrates broad support for public-private partnerships, government reforms to drive market innovations and adoption, tax incentives to promote investment, and support for medical exports — again, a sector that has been strongly held in the U.S. but is slipping given investments in education in China and India as well as targeted strategic support for the medical industry in those nations.

Six years ago when I stood in front of a board of a top 5 pharmaceutical company, I presented the outcome of a scenario planning project, detailing one of the four scenarios about novel pharmaceutical products being innovated and developed in China and India. The group pooh-poohed me, insisting that only generics could emerge from these emerging economies. Today, this scenario is very real. The U.S. medical innovation lead is indeed “ours to lose” without a concerted effort to not merely hold onto it, but re-energize the industry. It’s in the United States’ best interests for the nation’s long-term economic health.

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming  Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters

Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters  For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,