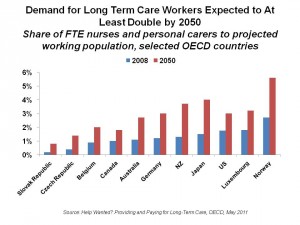

By 2050, the demand for long-term care (LTC) workers will more than double in the developed world, from Norway and New Zealand to Japan and the U.S. Aging populations with growing incidence of disabilities, looser family ties, and more women in the labor force are driving this reality. This is a multi-dimensional problem which requires looking beyond the issue of the simple aging demographic.

By 2050, the demand for long-term care (LTC) workers will more than double in the developed world, from Norway and New Zealand to Japan and the U.S. Aging populations with growing incidence of disabilities, looser family ties, and more women in the labor force are driving this reality. This is a multi-dimensional problem which requires looking beyond the issue of the simple aging demographic.

Help Wanted? is an apt title for the report from The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), subtitled, “providing and paying for long-term care.” The report details the complex forces exacerbating the LTC carer shortage, focusing on the fact that current policies to address this future are fragmented and piecemeal. Instead, OECD argues, policymakers must smartly weave together a comprehensive approach that addresses the many facets of the problem.

Statistically, in today’s world, 1 in 5 LTC users is under 65 years of age; one-half are over 80. Most of the LTC services paid-for are based in institutions: 62% of total LTC expenditures occur in institutional settings, not at home.

That simple aging demographic is the first aspect to consider: in 1950 under 1% of the global population was over 80. By 2050, that share will increase from 4% in 2010 to 10% in the OECD countries.

Today, it is informal, unpaid caregivers — usually family carers — who bear the brunt of long-term care.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The report states, “Family carers are the backbone of any LTC system.” That backbone is breaking in developed countries. More than 10% of adults over 50 living in an OECD country provides help with personal care to people who have limited ability to care for themselves. Without support, OECD says that caregiving is associated with a reduced labor supply for unpaid work, higher risk of poverty, and a 20% greater prevalence of mental health problems.

Supporting family caregivers is key to strengthening the backbone, and financial health, of long-term care infrastructures around the world. OECD’s solution is several-fold:

- First, to design financial support programs for caregivers in the form of allowances and cash benefits that would be paid to care recipients, which would increase the supply of family care.

- Second, to promote better work-life balance through family leave programs. While childcare leave is fairly common in most countries, family care (say, for aging parents) is not. Flexible work arrangements are a core part of this solution for carers working in full-time jobs. Care leave is most prevalent in Denmark, Poland, Finland, the Netherlands, Hungary, Sweden and Belgium.

- Third, support services such as respite care, training and counseling are key to managing eventual carer burnout and loss of personal control.

Still, even with these supports, OECD believes that over-reliance on family carers is not optimal. It’s the formal, labor-intensive LTC sector, that needs addressing. Currently, that sector is marked by high turnover and low retention, largely due to low pay, and lack of professional training and recognition and lack of technology support.

Improving job quality is key for LTC workers. The technology aspect could greatly turbocharge worker productivity and enhance job satisfaction, which better managing costs that are currently eaten up in institutional care. Implementing remote health monitoring, electronic health records, and personal safety response systems would keep older people safer and healthier at home, while enabling care workers to truly care and reduce their paperwork load and administrative hassle. Financing policies that speak to infrastructure-independent health care — not tethered to institutions — would move care back into peoples’ homes, where most would prefer to be to age in place and continue to be part of their local communities. Home care is a lower-cost alternative to institutional care today. As technology evolves to provide more care in home settings, evidence is gathering to prove cost-effectiveness of these approaches for chronic conditions like heart failure, COPD, and cancers. Furthermore, peer-to-peer care via online social networks can help homebound people feel and be connected with both people like them and caregivers.

While home-based LTC may not be clinically appropriate for very sick and/or frail seniors, appropriate utilization of institutional settings could be sorted out using clinical protocols and assessment tools.

Thanks to Feedspot for identifying

Thanks to Feedspot for identifying  Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.