The percentage of U.S. adults seeking health information declined from 2007 to 2010, according to the Health Tracking Household Study conducted by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), published in November 2011.

The percentage of U.S. adults seeking health information declined from 2007 to 2010, according to the Health Tracking Household Study conducted by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), published in November 2011.

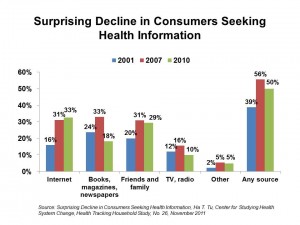

In 2007, 57% of consumers sought health information, falling to 50% in 2010, HSC found. The chart illustrates where the big drop in health information seeking occurred: in print media including books, magazines and newspapers, falling by one-half from 33% of consumers to 18%. The Internet (with 33% of consumers searching health information online) and friends and family (attracting 29% of consumers) remained relatively flat as information sources. TV/radio dropped 5.6 percentage points, down to 10% in 2010.

An important trend is in people seeking health information for others beyond themselves: 2 in 5 health info seekers are searching on behalf of another person. Caregiving thus drives people to health information seeking.

HSC points out that the decline in health information seeking has occurred across all demographic categories of consumers — but was most pronounced among older Americans, people with chronic conditions, and those with less education: “the more vulnerable subgroups who might most benefit from health information,” Ha Tu writes in the report.

Education is a key predictor of health information seeking, rising with higher levels of information. The disparity between information seeking among people with graduate education and those with no high school diploma grew since 2007.

The Tracking Report uses the HSC 2007 and 2010 Health Tracking Household Surveys based on telephone surveys and, in 2010, a cell phone sample of respondents. 18,000 U.S. adults were polled in 2007, and 17,000 in 2010.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I briefly discussed this study with Susannah Fox, author of The Social Life of Health Information and generally recognized expert on consumers’ use of the Internet in health. Her data from the Pew Internet & American Life Project has found relatively flat growth in health information seeking based on a base of people online. Pew’s stats are quite close to HSC’s: 80% of internet users, or 59% of U.S. adults, look online for health information.

The title of HSC’s report reads, “Surprise Decline in Consumers Seeking Health Information.” But what aspects of this story are surprising? Several underlying factors drive the statistical decline, and make sense in having done so:

- The recession hit most U.S. households hard. People are more tightly managing family budgets, and spending on non-necessities has been rationed since the advent of the Great Recession of 2008.

- Print media — hard-hit in the recession based both on their declining demand by people in favor of online channels — coupled with the relatively high-cost of accessing many print publications — has driven demand (that is, peoples’ willingness to pay for these media) down.

- Health education, and education overall, hasn’t improved much between 2007 and 2010. While there has been increased investment in so-called “unbranded” campaigns by pharmaceutical and medical device companies that seek to educate people on health conditions, it appears that in aggregate this spending hasn’t motivate sufficient numbers of additional health consumers to seek out health information.

Those who might need the health information most — older health citizens, and people of lower socio-economic status (esp. vis-a-vis educational attainment) — don’t seem to be driven to health information seeking. Notwithstanding more elderly Americans (over 65) increasing their personal Internet use, this did not translate into growth in health information seeking.

Ha Tu also points to a growing hypothesis about information overload: that there is so much health information available in health that many people get frustrated and anxious teasing out the ‘right’ information that they are looking for. This was addressed by Bawden and Robinson in a landmark article in 2009, The Dark Side of Information.

For people to optimally engage in health information seeking, and to participate in health, providers — the most trusted links in peoples’ health value chains — should engage back with patients to provide useful, accessible and culturally relevant information sources. New payment regimes such as accountable care and patient-centered medical homes should motivate this, and a new-and-improved era of participatory health.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.