The godfather of evidence-based medicine, Dr. David Sackett, said that the practice of evidence-based medicine integrates:

The godfather of evidence-based medicine, Dr. David Sackett, said that the practice of evidence-based medicine integrates:

- Individual clinical expertise

- A patient’s values and expectations

- The best available external clinical evidence.

If a physician’s got the first issue covered, and a patient is very engaged in their health in full collaboration with their physician, there’s still the third issue to deal with: the proliferation of medical information and keeping up with the literature.

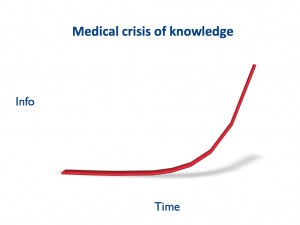

It’s impossible to be an expert, claimed two Welsh med school professors in the British Medical Journal in an honest appraisal of the “avalanche of information.” Today, med students training in cardiac imaging who read 40 papers a day for five days a week would need 11 years to get current with the specialty. Once completing that task, though, the students would be behind an additional 82,000 papers that would have been published in the interim, requiring 8 more years of reading….and so the need to play catch-up continues.

“We’re in a period where the cutting edge of change has moved from the technologies to the literacies made possible by the technologies,” wrote Howard Rheingold, Big Thinker on all things related to communication and the Internet. The theme of ever-growing medical knowledge and physician bandwidth for digital literacy set the stage for a recent blog post by one of the most digitally literate doctors in America, Bryan Vartabedian, MD.

Dr. Vartabedian writes the 33 Charts blog. Recently, he observed, “Something happened on the way to the clinic. The Internet democratized information and eliminated the traditional filters that contained medical knowledge. We suddenly were no longer limited by the space available on library shelves or the memory of a doctor.” Dr. Vartabedian, a pediatrician at Texas Children’s Hospital, is one of the leading physicians leveraging the power of the Internet in medical practice.

Dr. Vartabedian writes the 33 Charts blog. Recently, he observed, “Something happened on the way to the clinic. The Internet democratized information and eliminated the traditional filters that contained medical knowledge. We suddenly were no longer limited by the space available on library shelves or the memory of a doctor.” Dr. Vartabedian, a pediatrician at Texas Children’s Hospital, is one of the leading physicians leveraging the power of the Internet in medical practice.

In his blog post, The Case for New Physician Literacies in the Digital Age, Dr. Vartabedian makes 3 important observations:

- Physicians no longer control information

- There’s too much for physicians to “know” (note the drawing, illustrating the hockey-stick nature of information proliferation over time).

- Information will find us.

This last point is the opportunity, Dr. Vartabedian says, for information to “find us” based on our context. But how can the information find us when there’s so much to review? “You need a machine to help you,” judged a recent editorial in the British Medical Journal.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: That machine-based solution is what Elsevier’s ClinicalKey is working toward.

Dr. Vartabedian’s concept of information context isn’t lost on me, someone who covers the entire ecosystem of health and health care for every kind of stakeholder organization in the field. When I seek health information, I’m always asking questions in the context of a particular client’s point of view, filtering through my health economics lens.

The challenge for the physician of whom Dr. Vartabedian speaks is: what’s the context for that clinical question? Per Dr. Sackett’s paradigm introduced at the start of this post, who’s the patient? What are her particular preferences for a treatment site or therapeutic regimen? Where is the physician’s clinical expertise and knowledge base?

I had the pleasure of talking with Ellen Brassil, Director of the Health Sciences Library at Baystate Medical Center following the ClinicalKey mobile tour’s visit to her facility in Springfield, MA. Ellen told me that, “Title for title, ClinicalKey is one of the most valuable resources. What impresses me is that there is the quality to match the quantity” of searchable content, she said. “It has different dimensions, any one of which might fit the bill at any given moment, whether someone needs images for presentations, or is seeking an eBook or a specific journal title,” Ellen described.

Context also depends on physician workflow. “With greater integration of information in the electronic medical record at Baystate, that’s something more and more clinicians will be expecting where they can reach for relevant information that’s aligned with a clinical scenario or patient situation,” Ellen further explained.

I also spoke with Deborah Taylor, Assistant Professor & Acquisitions Librarian the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, after her visit with the ClinicalKey tour visiting Memphis. Deborah observed that, “Doctors need the journal articles with the most current information. As researchers, they also need information on grants, images for PowerPoint slides, and resources to build syllabi for students such as eBooks. ClinicalKey is good for research, classes, and medical practice,” she concluded after observing the ClinicalKey demo held at the University.

We are all working toward expertise in health care. Clinicians and medical information specialists are finding ClinicalKey to be a useful tool for building expertise, in context. And, ClinicalKey is helping highly relevant information to find its way to clinicians.

Stay tuned to future Health Populi posts on ClinicalKey in December, when I’ll address the issue of the physician time-squeeze. Elsevier is a paid sponsor of this blog post.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.