“The Internet will have a profound effect on the practice and business of medicine. Physicians, eager to provide high-quality care and forced by competition to offer online services, will introduce e-mail and patient-friendly Web sites to improve administrative services and manage common medical conditions. Patients will identify more helath information online and will take more responsibility for their care. The doctor/patient relationship will be altered. Some aspects of electronic communication will enhance the bond, and others will threaten it. Patients will have access to vast information sources of variable validity. Many physician organizations are preparing for the electronic transformation, but most physicians are unprepared, and many are resistant.”

So begins a 2000 article in Health Affairs by Dr. Jerome Kassirer titled Patients, Physicians and the Internet, expecting doctors to be emailing patients, and preparing for “electronic transformation.” As with all forecasts with twelve years of hindsight, some of the author’s expectations have come to pass, and others still challenge.

The sure bets in this forecast were that patients would regularly access health information online and that, “many physicians [have] predict[ed] that their time will be under even greater demand by a new barrage of Web-based material.”

The sure bets in this forecast were that patients would regularly access health information online and that, “many physicians [have] predict[ed] that their time will be under even greater demand by a new barrage of Web-based material.”

In 2012, physicians are seeking health information online via a variety of portals and platforms. But the information tsunami of which physicians were concerned still challenges doctors to keep up.

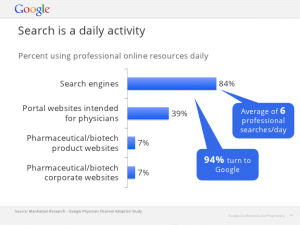

Nonetheless, by 2009, 9 in 10 U.S. physicians said using the Internet was “essential” to the clinical practice of medicine, according to Manhattan Research’s Taking the Pulse survey that year.

In February and March 2012, Manhattan Research worked with Google on a survey of online physicians and found that, in addition to the essential value of the Internet in health care, most doctors also believed that,

- “Search is the doctor’s digital stethoscope”

- Medicine is mobile

- Online video is an important educational platform.

However, while using the Internet in clinical practice is near-universal among physicians, their motives for going online vary. Researchers in Germany recently segmented physicians into four types of Internet users based on these motivations: they are,

However, while using the Internet in clinical practice is near-universal among physicians, their motives for going online vary. Researchers in Germany recently segmented physicians into four types of Internet users based on these motivations: they are,

– The Internet Advocates, who want to be on the cutting-edge and appreciate user-generated media

– Efficiency-Oriented physicians, who appreciate the Internet for speed, convenience and ease of finding information

– Driven Self-Expressionists, who see the importance of physicians being on the web. They appreciate the Internet and its convenience aspects and use online media for self-expression

– Internet Critics, the smallest physician segment, who are less motivated to use the Internet in clinical practice but among the highest use for their personal lives. These doctors may have poorer Internet literacy, the researchers hypothesized. They comprised only 10% of the total sample.

The first three segments of physicians have relatively positive attitudes about the Internet’s role in improving physician-patient relationships.

One of the key trends in physicians’ use of the Internet is going mobile, as the Manhattan Research/Google study indicated. Tablets (usually iPads which are beloved amongst physicians) have been fast-adopted: tablet use for professional purposes by doctors nearly doubled since 2011, reaching 62% in 2012. One-half of tablet-owning physicians use them at the point-of care. Furthermore, physicians with 3 screens (that is, tablets, smartphones and desktop or laptop computers) spend more time online on each device, and also go online more frequently during the workday compared with physicians using only one or two screens.

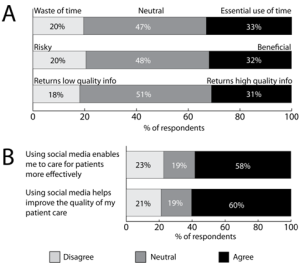

While Internet Critics are highly suspect of social media in health care, one in four U.S. physicians now use social media at least daily in clinical practice, according to a study in the Journal of Medical Internet Research. The graph illustrates that 33% of physicians found devoting time to social media was an essential use of time, more beneficial than risky, and with high quality information returns.

While Internet Critics are highly suspect of social media in health care, one in four U.S. physicians now use social media at least daily in clinical practice, according to a study in the Journal of Medical Internet Research. The graph illustrates that 33% of physicians found devoting time to social media was an essential use of time, more beneficial than risky, and with high quality information returns.

Most notably, over one-half of physicians said that using social media enabled better patient care in terms of effectiveness and quality. The key factors influencing a physician’s use of social media to share medical knowledge with other doctors were perceived ease of use and usefulness.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: This is the fifth and final post of my thinking about physicians seeking health information in the context of current health care dynamics and prospects for health reform on behalf of Elsevier and their launch of the ClinicalKey Experience tour. Elsevier took the proverbial show on the road to over 40 medical schools and teaching hospitals around the U.S. On the journey, C-suite hospital executives, medical librarians, physicians, nurses and residents got to experience ClinicalKey first-hand and search on topics they’re looked for via Google and other proprietary search portals.

I asked Mike LaMartina, ClinicalKey brand ambassador, who went on the road with the ClinicalKey mobile tour about his takeaways from the experience. “It didn’t matter which city we visited: while all hospitals are unique and different, there is one constant: everyone was happy to have us there, whether medical librarian, med student or physician. Everyone grabbed hold of the ClinicalKey concept. We didn’t travel cross-country to sell a product, but to demonstrate the benefits of it,” Mike said.

By going directly to the medical campuses, Elsevier was able to develop a trust between the staff and ClinicalKey. This was much more effective than a quick sales pitch at a large conference when users might take a minute or two to glance a brochure, or get a sales pitch. On average, hospital staff, whether physician or medical librarian, spent 7 to 10 minutes with hands-on the ClinicalKey software, conducting the types of searches they do in their daily work lives. What these users and prospects found was a quick on-ramp to finding high quality, current clinical information.

Mike talked about two residents who, once seeing they could export PowerPoint slides into their presentations, looked at each other with bewilderment and positively exclaimed, “No way!” followed by, “And we have this here at the hospital?!”

In another instance, a director of education learned that there was video content on ClinicalKey, so he sought a video on a specific procedure, found it, and was impressed with the quality of video. A similar scenario happened at a conference with an anaesthesiologist who saw a video on ClinicalKey and said, “I can use this in a guest lecture next week where I was looking for multimedia to include.”

Physicians particularly appreciated ClinicalKey coming to their campuses. This was unexpected and appreciated by busy physicians who don’t have time to attend conferences and take much time out of patient care, teaching and research responsibilities.

In previous posts, I’ve talked about the importance of time and efficiency, and managing information search into daily workflow. A third factor that emerged from the ClinicalKey tour was trust. ClinicalKey includes peer-reviewed patient guidelines and evidence-based information that are critical for physicians accessing clinical information portals. Their knowing that this content is available on ClinicalKey builds trust, which then encourages use of the system that can translate into high quality patient care.

Deborah Taylor, Assistant Professor and Acquisitions Librarian at the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center who hosted a ClinicalKey tour event, told me that she was, “impressed with one clinician whose opinions I respect who works closely with residents and medical students. After trying out ClinicalKey, she said, ‘I really trust these results.’”

Trust is further built through ongoing support and programs offered by ClinicalKey. “This is a partnership, not just a product,” Mike told me. ClinicalKey brings with it an ongoing process of bringing in leading resources backed by Elsevier’s brand as a leading medical publisher.

“We have to make it easy for users to access content; you don’t want them reading a narrative review and making decisions that way. We want them to continue to balance the art and science of medicine practicing with trusted information,” Cara Jesperson of Elsevier, said.

Thanks for reading my posts on ClinicalKey, which you can access in the Health Populi archive by searching on “ClinicalKey” here on the blog. This five-blog series was sponsored by Elsevier. All opinions included are mine, based solely on my own knowledge and experience.

Thank you Feedspot for

Thank you Feedspot for  Jane was named as a member of

Jane was named as a member of  I'm gobsmackingly happy to see my research cited in a new, landmark book from the National Academy of Medicine on

I'm gobsmackingly happy to see my research cited in a new, landmark book from the National Academy of Medicine on