In healthcare, we use the word “toxicity” when it comes to taking a new medicine, especially a strong therapy to cure cancer. That prescription may be toxic as a harmful side effect on our journey to getting well. The concept of “financial toxicity” for cancer patients was raised by concerned clinicians at Sloane-Kettering Medical Center, who discussed the topic on 60 Minutes in 2014 and have published papers on the issue.

In healthcare, we use the word “toxicity” when it comes to taking a new medicine, especially a strong therapy to cure cancer. That prescription may be toxic as a harmful side effect on our journey to getting well. The concept of “financial toxicity” for cancer patients was raised by concerned clinicians at Sloane-Kettering Medical Center, who discussed the topic on 60 Minutes in 2014 and have published papers on the issue.

Beyond strong medicines, a new financial toxicity has emerged for patients due to hospital inpatient admissions. A new article in the New England Journal of Medicine studies Myth and Measurement – The Case of Medical Bankruptcies written by four economists from UC Santa Cruz, MIT, and Northwestern University.

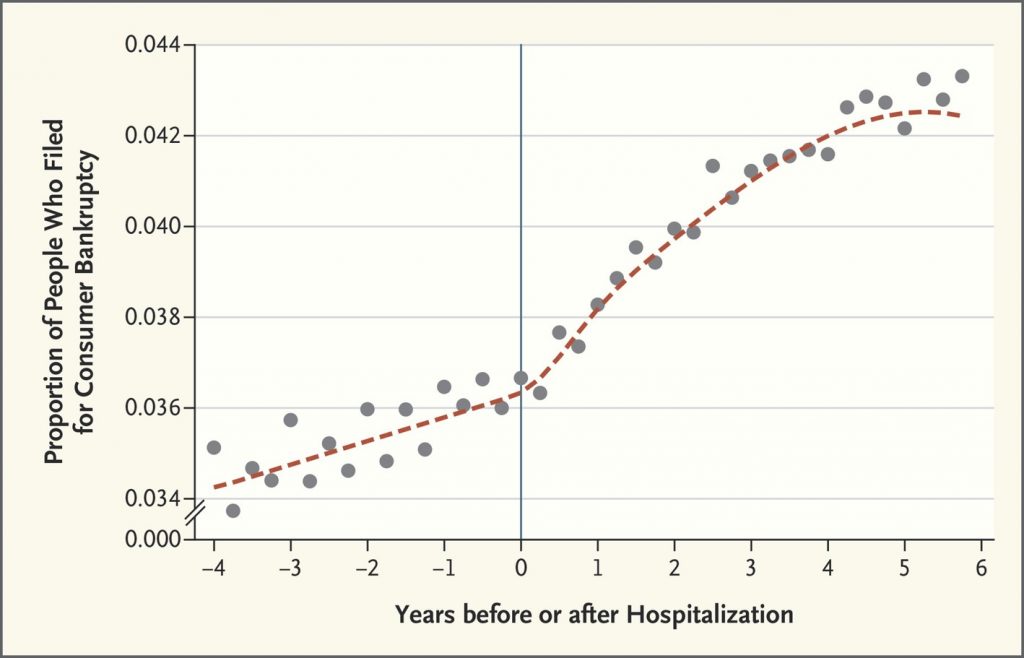

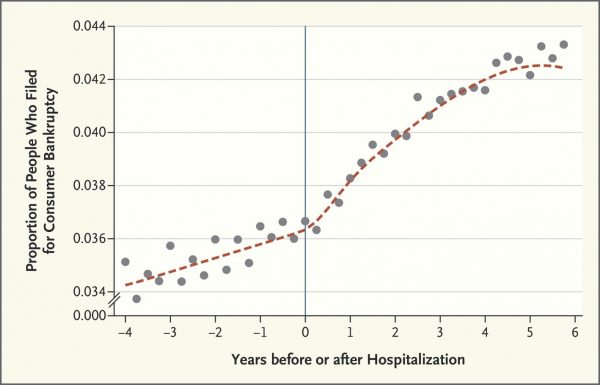

The “measurement” named in the title is graphed here as the proportion of people who filed for bankruptcy relative to years before or after hospitalization. The data points come from one-half million people who were hospitalized in California between 2002 and 2011 and tracked in credit reports which included information on whether and when the patients filed for bankruptcy.

The graph illustrates the effect of hospital admission on bankruptcy, with the rate of bankruptcies increase in the years after hospital admission, both one and four years after the admission.

The authors recognize that this study doesn’t cover all potential medical bankruptcies, like hospitalizations for children or elderly, and cover just patients in California. The data also don’t include people who are ill and injured but not admitted to hospital who may have high medical expenses. This is probably a smaller group of patients filing for bankruptcy, the authors believe based on other research they and others have conducted.

The study also leaves out data on the financial costs of hospital admissions among patients who did not file for bankruptcy. “We have found that hospitalizations cause increased out-of-pocket spending on medical care, increased medical debt, and decreased employment and income,” they write. “These costs may have considerable adverse consequences,” calling out the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment which saw that these adverse impacts can be helped by health insurance coverage.

The “myth” part of this study, the authors conclude, is that focusing on “medical bankruptcies” per se may obscure the larger issue impacting more U.S. health citizens of the economic hardship of high-cost health problems.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment found that having health insurance

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment found that having health insurance

Sommers, Gawande and Baicker write in the NEJM article on the Oregon experiment linked above, “Are the benefits of publicly subsidized coverage worth the cost?…expanding health insurance is a more cost-effective investment than many others we currently make in areas such as workplace safety and environmental protections. Factoring in enhanced well-being, mental health, and other outcomes would only further improve the cost–benefit ratio. But ultimately, policymakers and other stakeholders must decide how much they value these improvements in health, relative to other uses of public resources — from spending them on education and other social services to reducing taxes.”

Arguing that health insurance coverage doesn’t improve health is simply inconsistent with the evidence, the three researchers conclude.

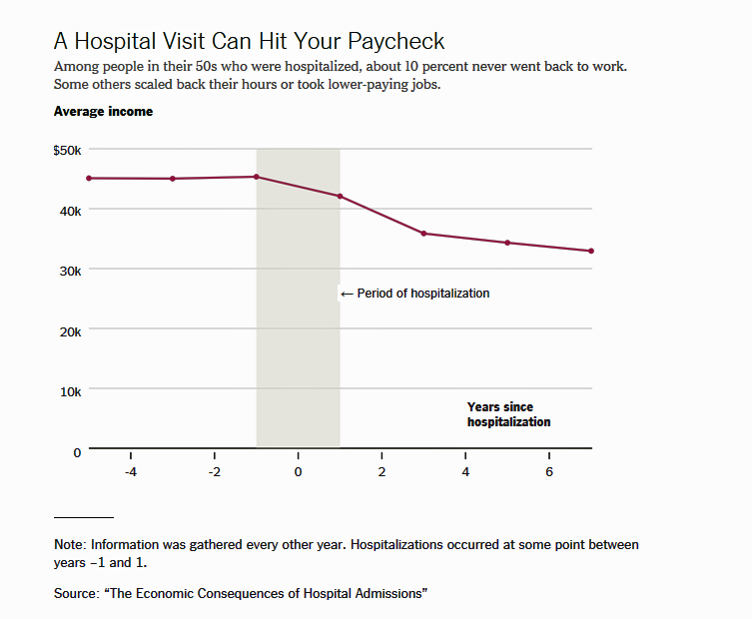

The Myth and Measurement essay is published this week at the same time as an important piece by Margot Sanger-Katz was published yesterday in the New York Times called Getting Sick Can Be Really Expensive, Even for the Insured.

The line chart illustrates data from an NBER study published in 2017 in the American Economic Journal, The Economic Consequences of Hospital Admissions, which shows that for working age adults with health insurance, hospital admission increase out-of-pocket medical spending unpaid medical bills and bankruptcy, and reduce income. Uninsured working age people bear an even bigger burden of unpaid medical bills and bankruptcy risk.

So health insurance, while imperfect, continues to be an important financial risk management tool for Americans. We can expect that the erosion of the Affordable Care Act and peoples’ access to insurance, in the short-to medium-term, will adversely impact some American families in light of the research discussed here.

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming  Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters

Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters  For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,