Two weeks in a row, The Economist, the news magazine headquartered in London, included two special reports stapled into the middle of the magazines. Universal health care was covered in a section on 28 April 2018, and coverage on financial inclusion was bundled into the 5th May edition.

While The Economist’s editors may not have intended for these two reports to reinforce each other, my lens on health and healthcare immediately, and appreciatively, connected the dots between healthcare coverage and financial wellness.

The Economist, not known for left-leaning political tendencies whatsoever, lays its bias down on the cover of the section here: universal healthcare is “an affordable necessity.” In making its case for universal healthcare (UHC), the writers acknowledge that the argument for UHC is clear, but difficult to reach.

The U.S. is a special case, an outlier, the report calls out. In the “Land of the free-for-all” discussion, the section notes that, “American made a good start” toward the end of the Civil War, noting that Abraham Lincoln announced there would be services, “to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphan.” At the time, this was one of the world’s biggest public-sector financed health plan. Over time, America’s approach to health care provision fragmented by plan sponsor, whether U.S. government (which offers several flavors of plans through the VA, Tricare for active military, Medicare for aging people and Medicaid for people with low-incomes) or private sector employers, unions, and other insurance-conveners.

Millions of Americans who are “insured” are now considered “under-insured,” defined by the Commonwealth Fund as people who pay an insurance premium who also spend over 10% of household income on covering health care co-payments and coinsurance percentages, and meeting deductible limits. For poorer citizens, that under-insured definition falls to spending 5% of household income on healthcare payments.

“America has a version of a problem seen the world over: voluntary insurance cannot ensure that everybody gets coverage,” the editors observe.

Affordability remains elusive in U.S. healthcare.

Keep that in mind as we turn to the second special report on financial inclusion, which the World Bank defines as peoples’ access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs, including transactions, payments, savings, credit and insurance, all delivered in a responsible and sustainable way. Financial inclusion is recognized as an engine for economic development that helps grow the GDP, improve individual and social well-being, and build small business.

Keep that in mind as we turn to the second special report on financial inclusion, which the World Bank defines as peoples’ access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs, including transactions, payments, savings, credit and insurance, all delivered in a responsible and sustainable way. Financial inclusion is recognized as an engine for economic development that helps grow the GDP, improve individual and social well-being, and build small business.

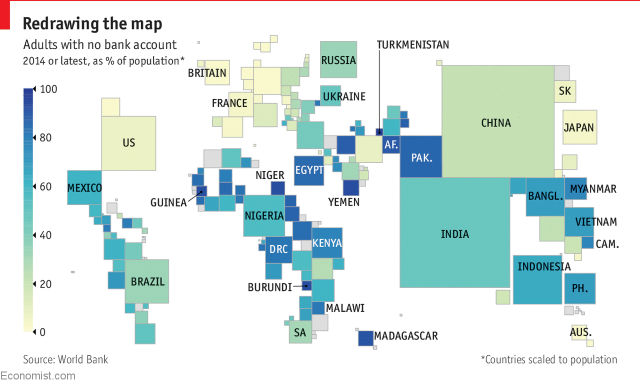

When it comes to financial inclusion, don’t let the map here fool you: while the US looks to be well-banked compared with financial citizens in other parts of the world, 109 million Americans fall below U.S. banks’ definition of “prime” customers, and 53 mm people are “credit invisibles” without sufficient financial history to build a FICO score. The Economist explains:

When it comes to financial inclusion, don’t let the map here fool you: while the US looks to be well-banked compared with financial citizens in other parts of the world, 109 million Americans fall below U.S. banks’ definition of “prime” customers, and 53 mm people are “credit invisibles” without sufficient financial history to build a FICO score. The Economist explains:

“In America the Centre for the New Middle Class, the think-tank arm of Elevate, a Texas-based onlin7e lender specialising in the “nonprime” market (not immediately creditworthy), estimates that 109m Americans are nonprime and a further 53m are “credit invisibles”, without enough of a financial history to be assigned a credit score. A survey by the Federal Reserve last year found that 44% of Americans would struggle to meet an unexpected expense of $400 without selling something or borrowing.”

Digital technology is not only useful for scaling healthcare service and health literacy/education access — the mobile phone is also a platform for medical banking and personal health financial management. Back to The Economist‘s financial inclusion report:

“Digital technology provides data through the apps that users download on their phones. Lenders say they can learn a lot from how, and how often, their customers use their app. Oakam, for example, offers an in-app game in which customers climb a “ladder” of client categories to earn a higher status and discounts. For people at the bottom of the credit pile, it is an apt metaphor.”

Now, connect the dots, at just the top-line: The Federal Reserve survey cited by The Economist found that 44% of Americans would “struggle” to meet an unexpected expense of $400 without selling something or taking out a loan.

Note the average costs for various health care services in the U.S.:

An emergency room visit = $580 to $700, according to Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Massachusetts

A root canal at the dentist = $762 to $1,111, according to FAIR Health

A prescription for EpiPen at retail = $630 for the branded version and $320 for generic, according to GoodRx.

I’ve been a regular reader of The Economist since leaving college, and it’s been essential content for me. These special sections make the case for The Economist being must-reading for lifelong learners who care about the world and its peoples.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The titles of the two special reports could be reversed: “An affordable necessity” could correspond to financial inclusion, and “exclusive access” to the reality of healthcare in America.

A common demographic underlies the covers of these sections: that the have-not’s living in developing nations — health citizens and financial citizens, both, at once — lack access to healthcare and banks.

As I pointed out with the “unbanked” map, which indicates that U.S. has a lower proportion of unbanked individuals than the developing world — what lies underneath is a much less sanguine story, which relates to both personal financial and individuals’ access to affordable healthcare.

These realities are intimately inter-related in the U.S.: addressing one without the other misses the point that the social determinants of health underlie Americans’ health and financial wellness.

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming  Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters

Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters  For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,