One in three working age people in the U.S. lost their job as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, some of whom lost health insurance and others anxious their health coverage will be threatened, revealed in a survey from The Commonwealth Fund published on April 21, 2020.

One in three working age people in the U.S. lost their job as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, some of whom lost health insurance and others anxious their health coverage will be threatened, revealed in a survey from The Commonwealth Fund published on April 21, 2020.

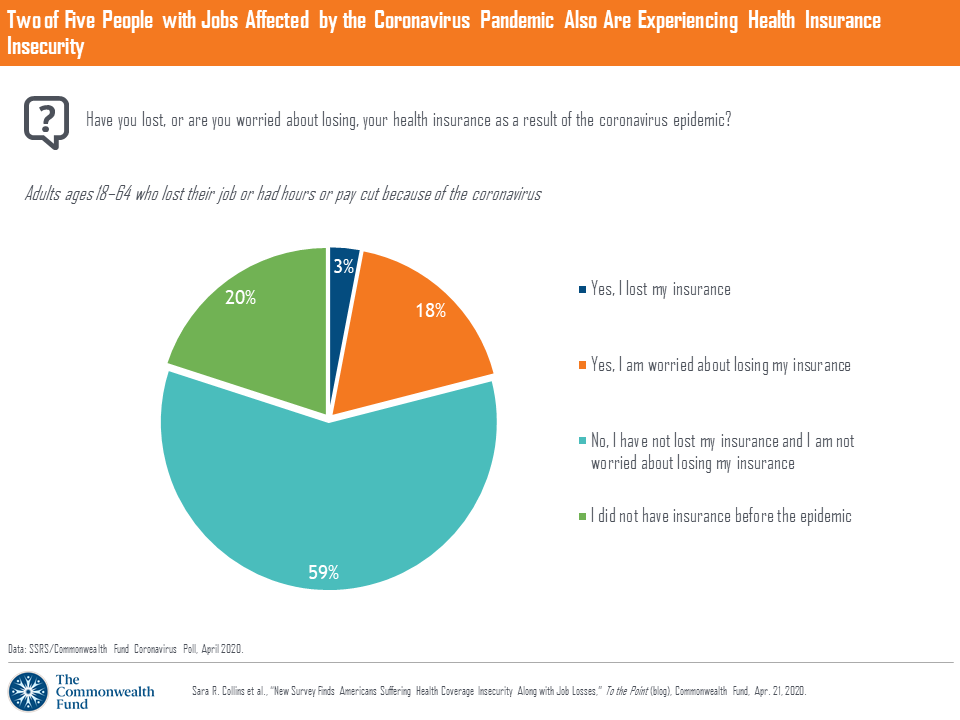

2 in 5 people in America who are dealing with job insecurity are also health insurance insecure, the study found, as shown in the pie chart.

The Commonwealth Fund commissioned the poll among 1,001 U.S. adults 18 to 64 years of age between 8-13 April 2020.

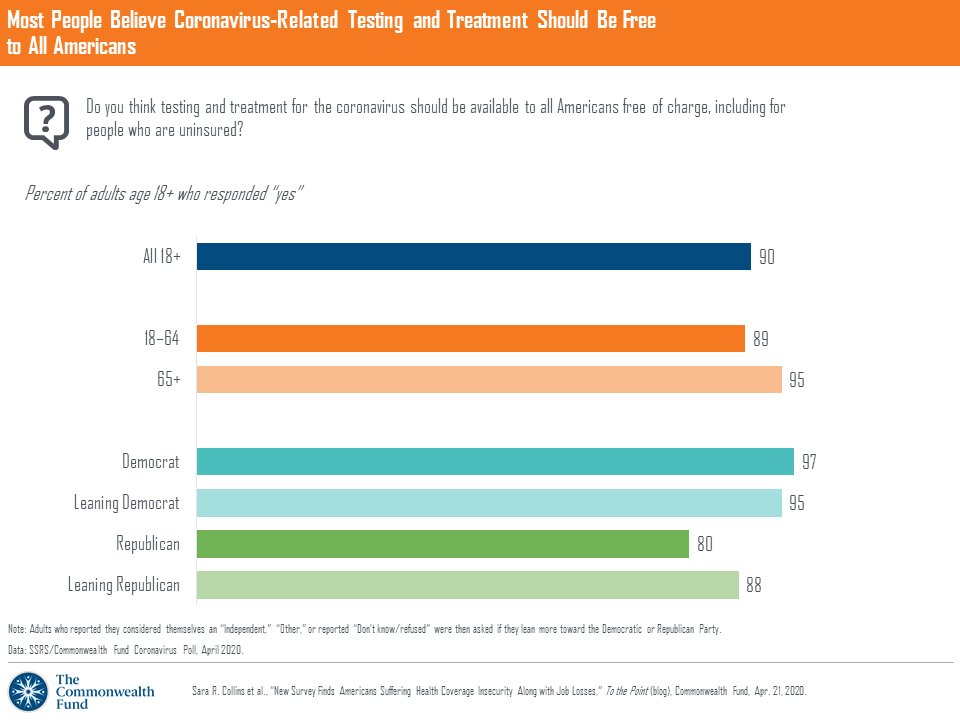

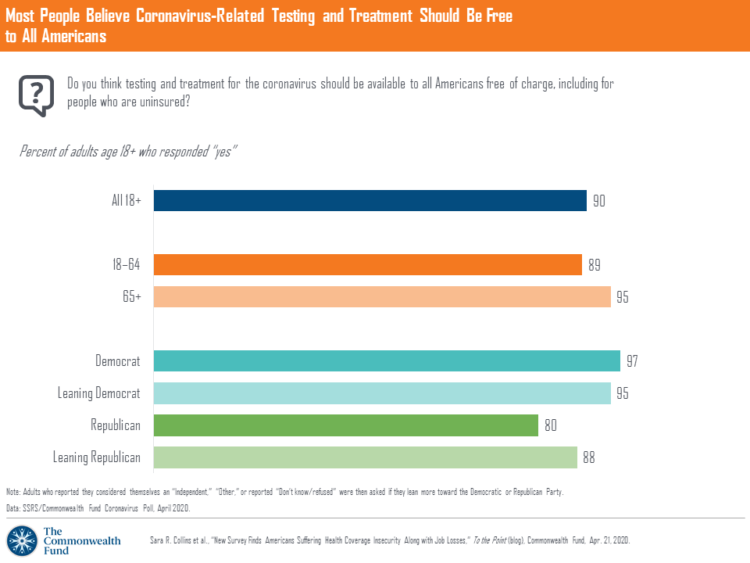

Nearly all Americans believe the dots of COVID-19 testing and treatment should be free to all. This majority opinion is shared across political party ID, Democrat (97%) and Republican (80%) alike.

Cost is a driver in most Americans’ decision of whether to seek care if they develop COVID-19 symptoms. Two in 3 U.S. adults told the Fund that the potential out-of-pocket costs would be important in deciding whether to seek treatment. This is more pronounced among people earning under $50,000 a year compared with those earning over $50K, but still 60% of the upper income health consumers said cost would play a role in deciding whether to seek COVID care.

Cost is a driver in most Americans’ decision of whether to seek care if they develop COVID-19 symptoms. Two in 3 U.S. adults told the Fund that the potential out-of-pocket costs would be important in deciding whether to seek treatment. This is more pronounced among people earning under $50,000 a year compared with those earning over $50K, but still 60% of the upper income health consumers said cost would play a role in deciding whether to seek COVID care.

Note that 77% of people who had lost their job or had hours or pay cut would figure cost into their decision whether to seek care for COVID symptoms.

The Fund points out in “Looking Forward” that 30 million people were already uninsured in 2018, with 44 million people underinsured due to high deductibles that were beyond the insured’s ability to afford based on their income.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The era of the coronavirus has revealed many deficiencies of the U.S. health care system: among these faults, health disparities, supply chain weaknesses and dependencies, the lack of public health planning and resourcing and, in the case of this Commonwealth Fund research, health financial insecurity for a plethora of patients.

The Fund’s analysis reveals the weakness of an employer-based health care design for covering a nation’s population with health insurance. In fact, just about one-half of Americans receive health insurance from the workplace, and in the lightning-fast downturn of employment, coverage can be quickly cut out from a worker’s life — and her family’s. If COBRA extension for insurance is available to the worker, in the case of job loss, the unemployed person may not be able to cover the cost of continuing an insurance plan given competing priorities for paying for housing, food, and other basic needs.

There is evidence that with the CoV pandemic, sick patients are forgoing care. Self-rationing due to cost is not a new-new thing, as I’ve covered this uniquely U.S. health consumer challenge for many years here in Health Populi. But in the COVID-era, some people who are quite sick are forgoing care due to concerns about their immunity or frailty, beyond their medical costs which can also be top-of-mind. The New York Times published an article today titled, “The Pandemic’s Hidden Victims: Sick or Dying, But Not From the Virus,” highlighting the “gray zone of medical risk:” when patients aren’t acutely ill but concerned about the risks of entering the medical system in the COVID pandemic. For example, in L.A. County, public hospitals are concerned that patients are waiting too long to seek care.

There is evidence that with the CoV pandemic, sick patients are forgoing care. Self-rationing due to cost is not a new-new thing, as I’ve covered this uniquely U.S. health consumer challenge for many years here in Health Populi. But in the COVID-era, some people who are quite sick are forgoing care due to concerns about their immunity or frailty, beyond their medical costs which can also be top-of-mind. The New York Times published an article today titled, “The Pandemic’s Hidden Victims: Sick or Dying, But Not From the Virus,” highlighting the “gray zone of medical risk:” when patients aren’t acutely ill but concerned about the risks of entering the medical system in the COVID pandemic. For example, in L.A. County, public hospitals are concerned that patients are waiting too long to seek care.

For breast cancer patients, there’s been an initial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic documented by the National Breast Cancer Coalition in a survey conducted among 564 patients in late March 2020. 1 in 5 patients had a challenge accessing breast cancer care related to the virus, most likely seeing their appointment postponed. Another 17% were concerned about payment and out-of-pocket expenses for treatment.

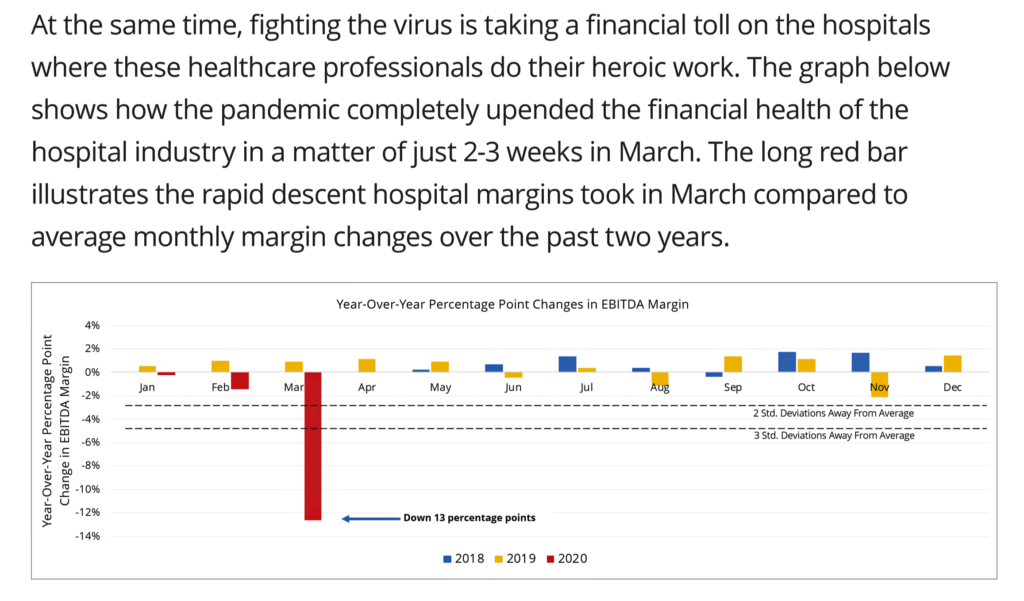

That’s the patient-consumer demand side of the COVID-19 payment equation. Consider the hospital’s lens on this: Kaufman Hall published their April 2020 hospital flash report this week, with this chart on the negative EBITDA margin that hit U.S. hospitals hard in March 2020. That is the acronym for “earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization.” As Kaufman Hall put it in the accompanying paragraph, this illustrates, “how the pandemic completely upended the financial health of the hospital industry in a matter of just 2-3 weeks in March.”

That’s the patient-consumer demand side of the COVID-19 payment equation. Consider the hospital’s lens on this: Kaufman Hall published their April 2020 hospital flash report this week, with this chart on the negative EBITDA margin that hit U.S. hospitals hard in March 2020. That is the acronym for “earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization.” As Kaufman Hall put it in the accompanying paragraph, this illustrates, “how the pandemic completely upended the financial health of the hospital industry in a matter of just 2-3 weeks in March.”

The coronavirus pandemic illustrates the inextricable linkage between the physical and the fiscal for the American patient — and hospitals. That is, the all-American relationship between health, health care and money.

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming  Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters

Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters  For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,