As physicians deal on the frontlines in Year 3 of the COVID-19 pandemic, they’re stressed, anxious, and angry concludes the Medscape 2022 Physician Burnout & Depression Report. This year, the tagline focuses on stress, anxiety and anger. [Over the past couple of years, the study has used the word “suicide” in the title of the report, FYI].

As physicians deal on the frontlines in Year 3 of the COVID-19 pandemic, they’re stressed, anxious, and angry concludes the Medscape 2022 Physician Burnout & Depression Report. This year, the tagline focuses on stress, anxiety and anger. [Over the past couple of years, the study has used the word “suicide” in the title of the report, FYI].

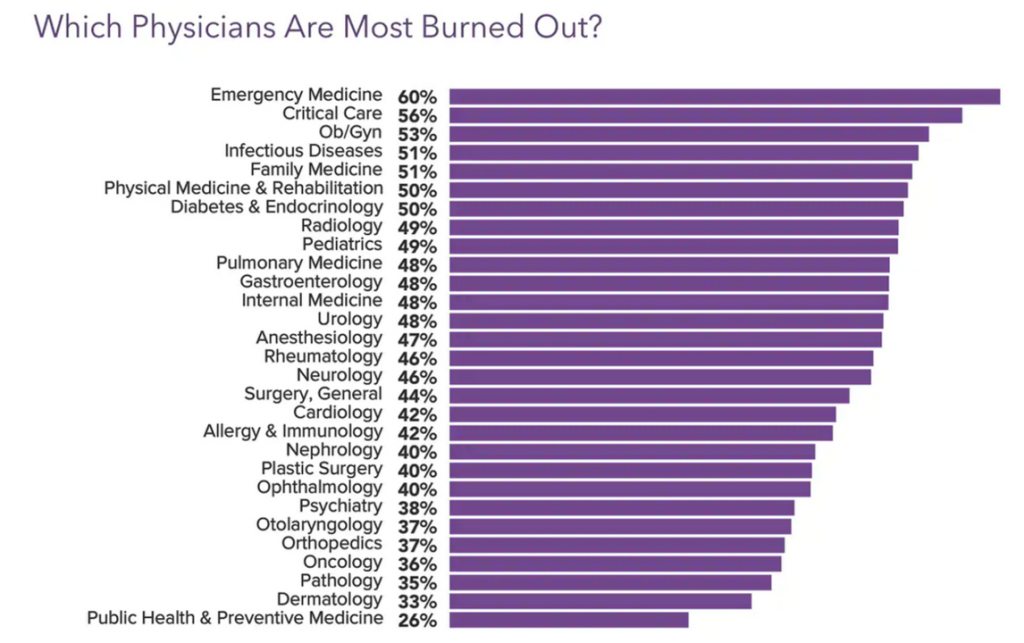

Those reporting burnout are more likely women physicians than males (56% vs. 41%), work in the ER or critical care departments, and deal with too many bureaucratic tasks like charting and paperwork.

For this annual look into the state of U.S. physicians mindsets and mental health, Medscape polled 13,069 physicians across 29 specialties between late June and September 2021 via a 10-minute online survey.

During the quarantine months of COVID-19, one-half of male doctors felt more burned out compared with 60% of women who reported burnout.

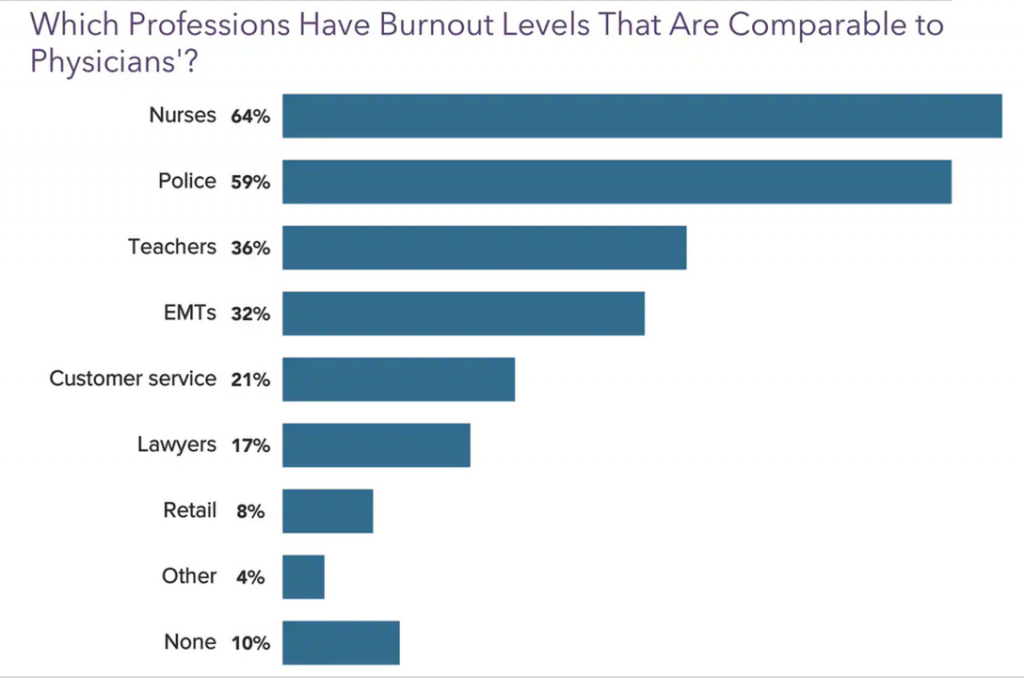

When asked which professions have burnout levels comparable to physicians, doctors pointed first to nurses (64%), followed by police (59%) and then teachers and EMTs (36% and 32%, respectively).

When asked which professions have burnout levels comparable to physicians, doctors pointed first to nurses (64%), followed by police (59%) and then teachers and EMTs (36% and 32%, respectively).

While 53% of doctors said their depression did not affect their interaction with patients,

- 34% of doctors said they were “easily exasperated” with patients

- 23% were less motivated to be careful with taking patient notes

- 14% expressed frustration in front of patients, and

- 11% confessed to making errors that they might not ordinarily make.

It would be no surprise to note, then, that COVID-19 has affected physicians’ work-life happiness. Prior to COVID-19, 68% of physicians said they were happy with work and life; currently (2021), only 47% of doctors said they were happy.

At the workplace, 41% of doctors said they were not offered a program to reduce stress and/or burnout (42% were offered such a program)

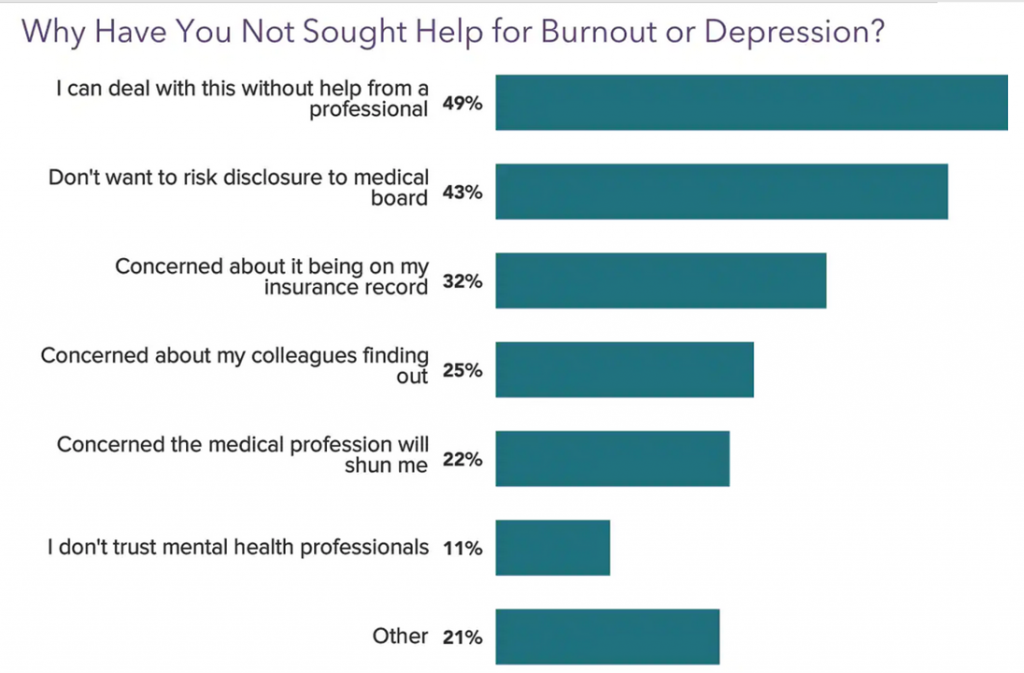

As in other years’ Medscape studies, a plurality of physicians did not seek help for burnout or depression: this year, one-half of doctors said they could deal with the mental health challenges without help from a professional, and 43% said they didn’t want to risk disclosure to a medical board.

As in other years’ Medscape studies, a plurality of physicians did not seek help for burnout or depression: this year, one-half of doctors said they could deal with the mental health challenges without help from a professional, and 43% said they didn’t want to risk disclosure to a medical board.

Another one-third were concerned about this clinical claim being on their insurance record, one-fourth worried about colleagues finding out about their burnout or depression, and 22% concerned the medical profession would “shun me.”

Bolstering this point of so many physicians avoiding mental health support, 43% had not used the services of a company or individual who offered programs to reduce burnout and would not consider using such a program.

How do physicians cope with burnout? Most likely, doctors deal with burnout through exercise (48%), isolating themselves from others (45%), talking with family and friends and getting sleep (41%), playing or listening to music (35%), or eating junk food (35%).

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I have a love/hate relationship with this study: I embrace the data and value it, but my empathy for clinicians dealing with burnout, depression, anxiety, and indeed suicide, compels me to share these findings year after year to help address the taboo that, clearly, many physicians feel confronts them in dealing with mental health challenges.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I have a love/hate relationship with this study: I embrace the data and value it, but my empathy for clinicians dealing with burnout, depression, anxiety, and indeed suicide, compels me to share these findings year after year to help address the taboo that, clearly, many physicians feel confronts them in dealing with mental health challenges.

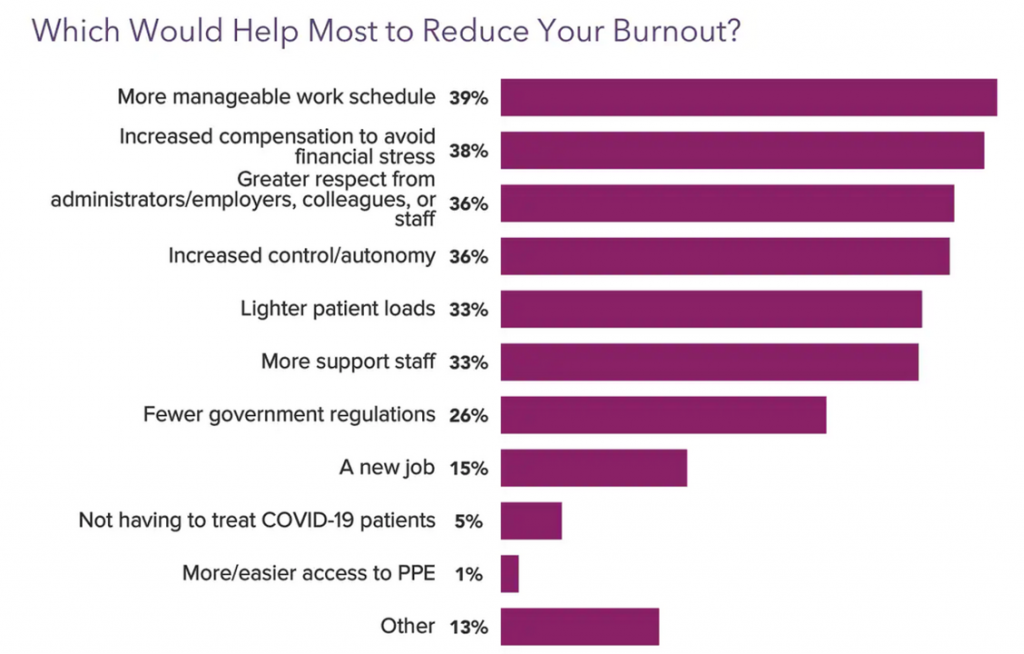

How can we better support physicians? When asked what would help most to reduce burnout, Medscape learned that at least one in three physicians noted,

- A more manageable work schedule

- Increased compensation,

- Greater respect from colleagues (from administration to colleagues and staff)

- Increased control and professional autonomy, and

- More support staff

would each bolster doctors’ mental health at the workplace.

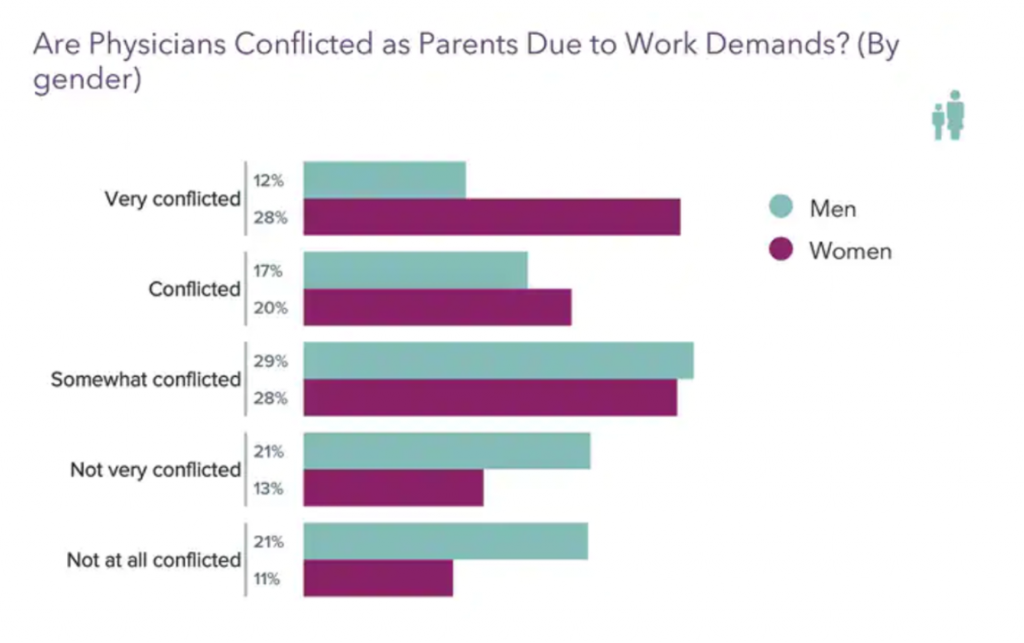

We should also speak to the burnout/depression difference between female and male physicians noted at the start of the post: that is, that 56% of women doctors felt burned out in 2021 versus 41% of male doctors.

We should also speak to the burnout/depression difference between female and male physicians noted at the start of the post: that is, that 56% of women doctors felt burned out in 2021 versus 41% of male doctors.

This last bar chart digs deeper into the Mars vs. Venus delta in physician burnout. Note that more women physicians felt conflicted as parents due to work demands than doctor-Dads. In terms of “net conflicted” (very conflicted + conflicted), 48% of women doctors felt conflicted as parents compared to 29% of male doctors.

Interestingly, 55% of physicians overall told Medscape they would take a salary reduction to have better work-life balance. We don’t know the male/female split on this data point based on the study report. We know that 1 in 3 doctors said increased compensation to avoid financial stress would help address burnout and depression, noted in the previous chart.

There’s a Great Resignation already happening in the health care workforce, noted by the Mayo Clinic Proceedings in this study. One in 5 U.S. physicians was intending to leave the profession within 2 years.

“Feeling valued by one’s organization: this was associated with less intent to reduce hours or leave one’s job,” the research concluded. “Mechanisms to enhance health care workers’ sense of value are needed. Transparent communication, support for child care, and rapid training to support deployment to unfamiliar units may demonstrate organizational appreciation to workers,” they recommended.

For looks into previous Medscape physician burnout reports, you can see my take on these links by year…

2021, Dr, Burnout – the 2021 Physician Burnout & Suicide Report

2020, Physicians in America – Too Many Burned Out, Depressed, and Not Getting Support

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming  Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters

Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters  For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,