“Tech giants are the primary forces driving digital transformation forward,” and this is especially the case for health care systems re-imagining how health care services are delivered and “consumed.”

This observation comes from a new report, Tech Giants in Healthcare, written by four European-based experts in healthcare and bioethics. The 200-page paper details the activities of sixteen global technology companies in the health/care ecosystem, followed by a so-called “ethical analysis” of these companies’ work with health data. The report was published in Germany by Bertelsmann Stiftung, a not-for-profit think tank addressing broad political, social and economic issues.

The report is rich with both data and frameworks that are useful to this week’s Retail Health Battle Royale brainstorm here in Health Populi as well as broader considerations for digital health ethics and health citizenship for U.S. health/care stakeholders.

Let’s start with the definition of “tech giants” here: the authors address technology companies “unique regarding their expertise in digital technologies,” they write, with substantial access to financial, human, and technical resources to leverage.

Entering healthcare, these companies are, in the words of the authors, “”pursuing both their own economic interests and — according to their own statements — the goal of using digital innovations to significantly improve health(-care) behavior and healthcare provision, and thus individual and public health.”

As such, these huge enterprises have “authority” to shape individual and societal expectations and demands, the paper explains, effectively determining the boundaries of what is deemed possible in healthcare.

This is why the second half of the report covers the “Ethical Analysis” — exploring risks for individual health citizens and societies-at-large.

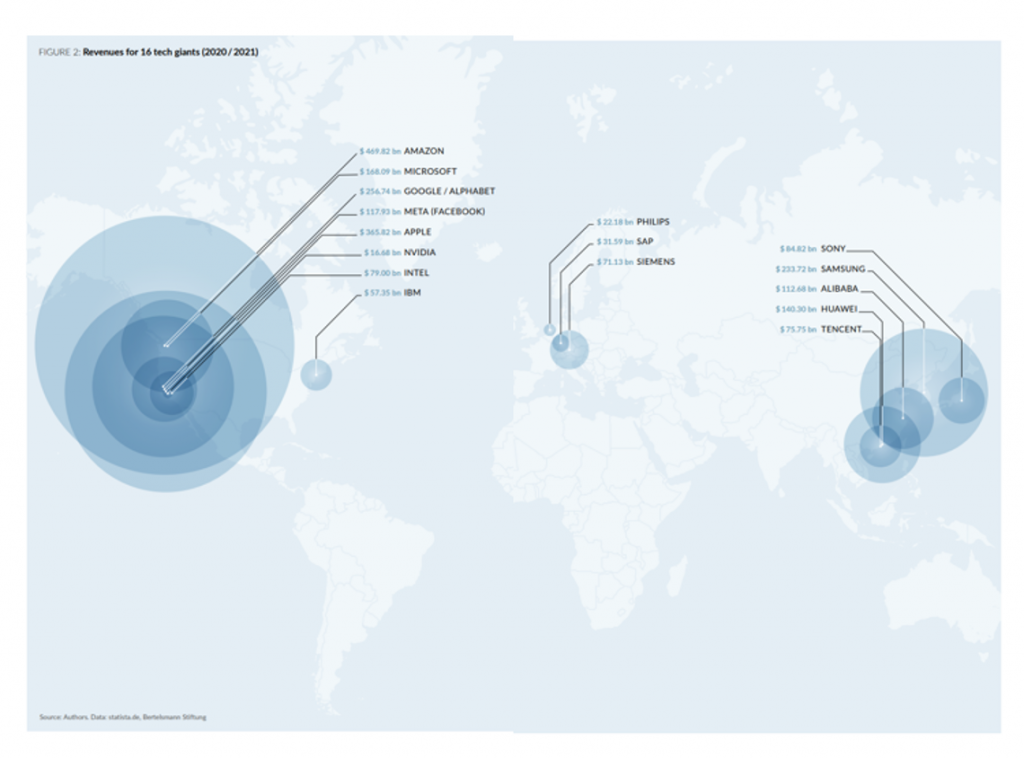

The second diagram shows the mapping (literally) of the sixteen Tech Giants that service the bulk of the world’s collective digital services supply. In North America, these include Amazon, Microsoft, Google/Alphabet, Meta/Facebook, Apple, Nvidia, Intel and IBM. In Europe, we look at Philips, SAP and Siemens. In Asia, the report points to Sony, Samsung, Alibaba, Huawei, and Tencent.

Thus, while some might focus on a “GAFAM”-centric view of Big Tech in health care (that is, Google, Apple, Meta/Facebook, Apple and Microsoft), this report widens our worldview, literally, on the tech giants serving health care globally. These are the enterprises the authors say, “have vast financial means at their disposal,” having achieved economic success and dominant market positions.

In assessing these companies’ health care activities, the report asked six questions including,

- What products and services were the companies using or developing specifically for healthcare?

- Which areas of healthcare were particularly attractive from the tech giants’ perspective?

- What activities are planned for the digital transformation of healthcare?

- What ethically relevant opportunities and challenges were associated with the companies’ activities in German healthcare?

- How much power will the tech giants be able to develop in healthcare, and what form(s) would that take? and,

- What measures and structures can be recommended to deal with the companies’ health care activities, particularly addressing ethical standards?

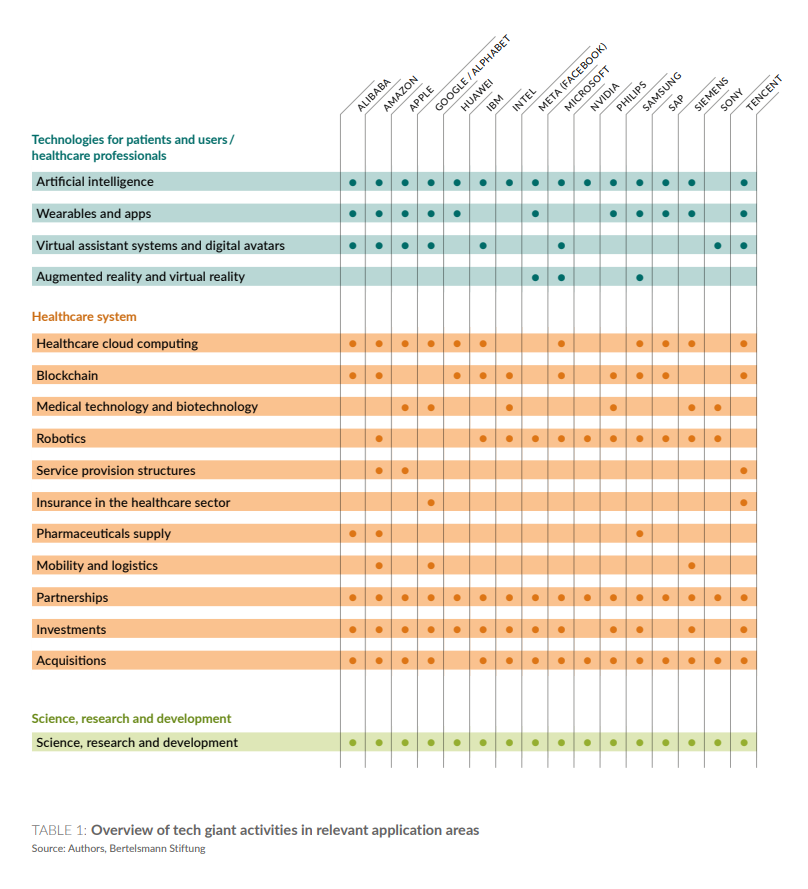

The analysis looked at four application areas: tech’s for patients and users, tech’s for healthcare professionals, Healthcare systems, and Science, research and development

The grid diagram summarizes the findings for each of the sixteen Tech Giants service the technologies and healthcare system market segments. While a snapshot in time, this diagram makes clear that Amazon is active across most of the technologies and health system services. Augmented reality and virtual reality (AR/VR) were bigger focuses for Meta/Facebook, Microsoft, and Samsung. Virtually all of the giants, except for Sony, provided AI analysis for healthcare.

You can review the next 80 pages of the reports for deeper dives into each of these areas for every company.

My own deeper dive was into the Ethical Analysis, which is not commonly done in U.S. business plan reviews, except for assessments of companies’ ESG efforts for environmental, social, and governance which is still fairly nascent in American health care reports.

Why worry about ethical values in digital health technologies?

It’s the data, and its very personal nature.

“Health technologies affect fundamental values such as life, health, liberty and justice,” the Tech Giants report calls out introducing this section of the paper.

That sentence has an echo of the U.S. Declaration of Independence’s “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” doesn’t it?

And so we can look at the eight pillars of ethical principles the authors cite to provide a framework for evaluating digital health fairness and equity, listed in the graphic here. [For more on each of these eight values and how they translate into health care, see my recent essay for Medecision on Equity-By-Design for U.S. healthcare].

I’ll call out two of the eight here in light of the current challenges to health data privacy and access to services in the U.S.: Privacy and Democracy.

“The right to privacy is intended to preserve an individual’s freedom and the integrity of his or her personal identity…includ[ing] the wholesale collection and evaluation of data about even the most intimate of topics,” the report sets forth.

The principle of privacy is intertwined with human dignity and self-determination, the authors assert. “Everyone has the right to protect their own privacy even within the public sphere….and…the right to lead a self-determined life.”

For democracy to flourish, they note that digital technologies are of “systemic relevance,” making it possible to shape new forms of political participation,” but also potentially fostering the emergence of threats such as “manipulation and radicalization.”

The Holy Grail of digital technologies, we can conclude from this discussion, is to enable “the participation of citizens in the shaping of society….(of) fundamental importance for democracy,” the chapter concludes.

Health Populi’s Health Points: The growing retailization of health care also has the promise of democratizing access, convenience, cultural relevance, and community engagement.

Underpinned and informed by health consumers’ personal data, there is also the promise of personalization and care coordination specific to each of our “Ns of 1,” to help us be more proactive, preventive, or if we receive a new diagnosis, to receive therapeutic guidance based on more complete, current actionable information.

However, that promise is compromised by the fact that, “the ability to use interoperable digital technology to improve the effectiveness, efficiency, equity, and continuity of care remains substantially conceptual,” according to The Promise of Digital Health: Then, Now, and the Future. Published in late June 2022 by the National Academy of Medicine, this paper crowdsourced views of over two dozen of America’s smartest voices in health care including Amy Abernethy of Verily, Atul Butte of UCSF, Judith Faulkner of Epic Systems, John Halamka of Mao Clinic, Devon McGraw of Ciitizen Corporation, Peter Lee of Microsoft, Lucia Savage of Omada Health, Paul Tang of Stanford, Eric Topol of Scripps, and Kristin Valdes of b.well Connected Health, among many others.

This paper reviews digital health tools and the many issues to overcome in order to get to that promise of digital health.

The circle diagram comes from the NAM paper, identifying what the authors call the “infrastructure requirements” but also reflecting some of the ethical pillars called out in the Tech Giants paper. In addition to equity and ethics, privacy, and access, this perspective adds in data quality, data stewardship, governance, and other critical factors that can, together, bolster digital health’s relevance and effectiveness for all health citizens, no matter what ZIP code people live in, their race/ethnicity, or their type of health insurance coverage.

Circling back to the Tech Giants and their connection to retail health, we must be mindful when designing digital health tools — embedding equity-by-design principles — recognizing that scale has its benefits for analyzing health data within and across populations. While Europeans are covered by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) for all personal information, in the U.S., HIPAA continues to have holes and data “leakages” that can compromise peoples’ trust and confidence in health data systems, along with their faith in care delivery.

In my conception for U.S. health citizenship, our digital lives are coupled with a comprehensive privacy law that inspires us to trust American health care providers and other stakeholders in our personal health/care ecosystems.

In tomorrow’s Day 5 of the Retail Health Battle Royale series, I’ll conclude our week by connecting the dots across all four of the week’s posts and learnings, and bring some new insights into the update and outlook for health care in America that’s more equitable, accessible, and enchanting.

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast  This conversation with Lynn Hanessian, chief strategist at Edelman, rings truer in today's context than on the day we recorded it. We're

This conversation with Lynn Hanessian, chief strategist at Edelman, rings truer in today's context than on the day we recorded it. We're