What happens to a health care ecosystem when the volume of patients and revenues they generate decline?

Add to that scenario a growing consensus for a likely recession in 2023. How would that further impact the micro-economy of health care?

A report from Trilliant on the 2022 Trends Shaping the Health Economy helps to inform our response to that question.

Start with Sanjula Jain’s bottom-line: that every health care stakeholder will be impacted by reduced yield. That’s the fewer patients, less revenue prediction, based on Trilliant’s 13 trends re-shaping the U.S. health economy. These are shown in the first diagram from the report, breaking out factors that have exacerbated challenges on both the demand and supply side of the American health economy. Many of these were already in motion before the COVID-19 pandemic emerged; the public health crisis exacerbated several of them.

On the demand side — focusing on patients — several forces are quite sobering to confront. In the U.S., life expectancy has fallen for the second year in a row, the largest increase in mortality across all developed nations. That was 2.7 years: blame it on the pandemic, heart disease, and the continued challenge of the Deaths of Despair.

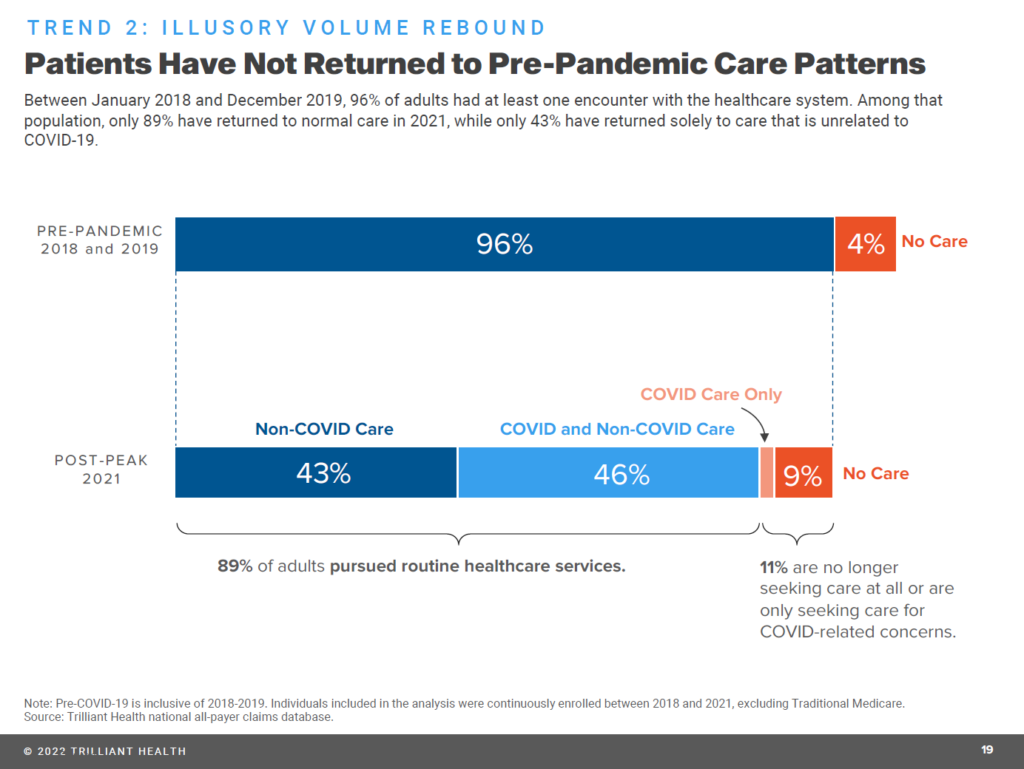

The second drawing illustrates the fact that health care service patterns have not returned to their pre-pandemic levels.

Health care utilization declined due to patients foregoing, rather than delaying, care. Aside from care for COVID-19, volumes are down except for services related to mental and behavioral health (with rates of mental health prescribing increasing for antidepressant and anti-anxiety drugs).

Some of the decline in service volumes has been for screenings and preventive care, which will result in underdiagnosis of, for example, cancer conditions further downstream — with more acutely, advanced cases requiring more aggressive (and potentially expensive) treatments.

That’s a summary of the demand side of the trends on the health economy which serve up huge challenges for legacy health care stakeholders: hospitals and health systems, health plans, pharmaceutical and medical tech companies, and clinicians.

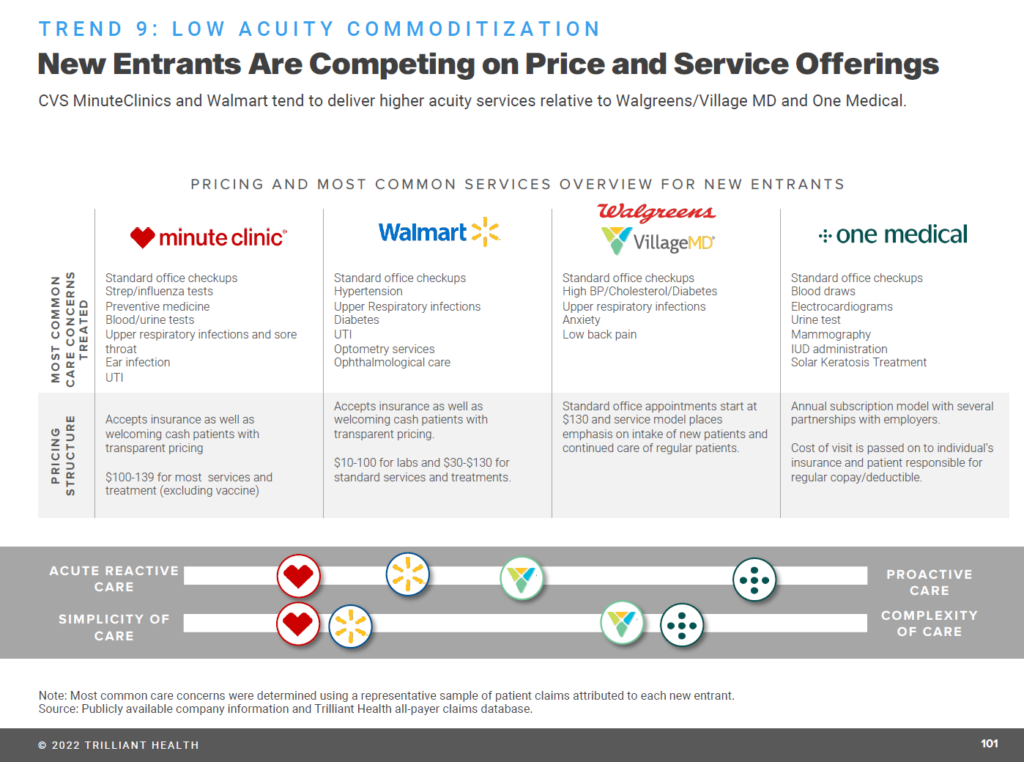

On the supply side, these health care incumbents are also faced with growing competition for some aspects of their services from new entrants, competing on the basis of price and programs. The Trilliant report provides the snapshot shown here for four competitors based on the most common “low acuity services:” for CVS Health’s Minute Clinic, Walmart, Walgreens/VillageMD, and Amazon’s One Medical.

These providers generally offer health consumers greater price transparency and lower prices for commodity-type services, along with more retail-friendly service experiences long eluding brick-and-mortar hospitals, outpatient clinics, ambulatory care centers, and physician offices.

That level of service and price satisfaction builds health consumers’ loyalty and trust. Trilliant points out that “existing consumer loyalty increases competitive pressures on traditional providers,” noting that 62% of U.S> adults have an active Amazon Prime membership (adjacent to One Medical’s primary care services), and that 42% of Americans shop at a Walmart location every week.

Contrast those statistics with the fact that fewer than 2% of Americans are treated at any given health system.

Scale matters in building services, competitive pricing, and digital health-tech infrastructures.

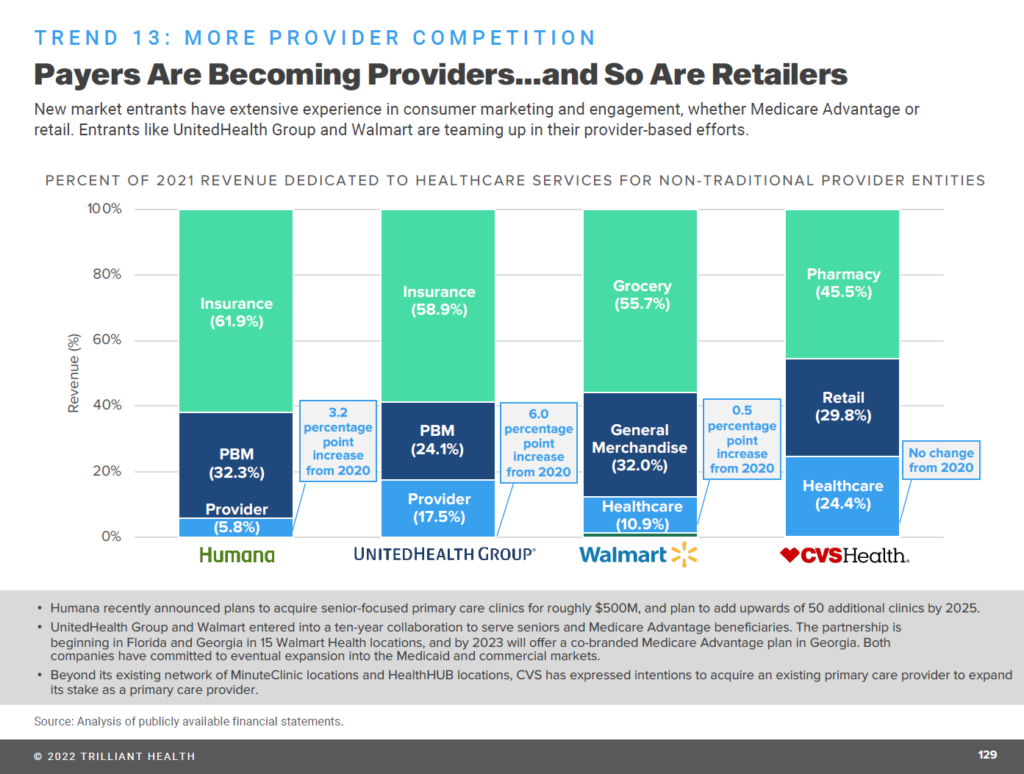

Digital transformation is taking hold in provider organizations — enabling payers to morph into providers, and also non-traditional organizations like retail pharmacies and Big Box stores (e.g., Walmart) to do so, as well.

Add into this picture a CCS Insight analyst’s forecast last week that Apple could enter the health insurance market in 2024.

I had asked some years ago, “what is a pharmacy” anymore, when CVS Pharmacy dropped tobacco from its SKUs and aisles in February 2014, rebranding as CVS Health; and, when Amazon purchased PillPack in June 2018.

In the meantime, the number and types of health care services competitors is proliferating across many flavors, Trilliant points out, for women’s health care providers, tech-enabled providers, retail-based channels, and home-based care.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: With these factors in mind, how would an economic downturn impact the demand/supply dynamics for U.S. health care? And what should incumbents — hospitals, plans, providers, and med-tech firms — embed into strategies?

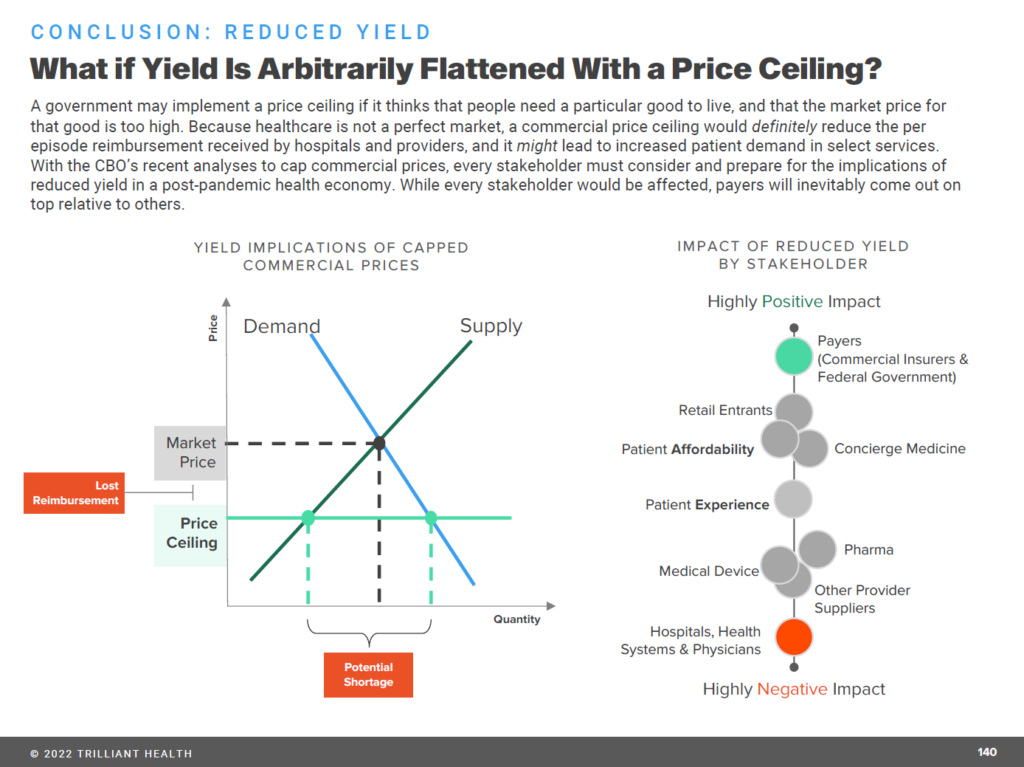

Trilliant asks the bottom-line question with this last chart: “What if yield is arbitrarily flattened with a price ceiling.”

Over 11 years ago, I listened to Dr. Toby Cosgrove, then CEO of The Cleveland Clinic, warn in his 2011 State of the Clinic annual address that, “we have to do better with less.” Dr. Cosgrove based that sobering forecast due to changes in the U.S. health care system not seen since the 1968 creation of Medicare, coupled with decreased reimbursement due to health care reform.

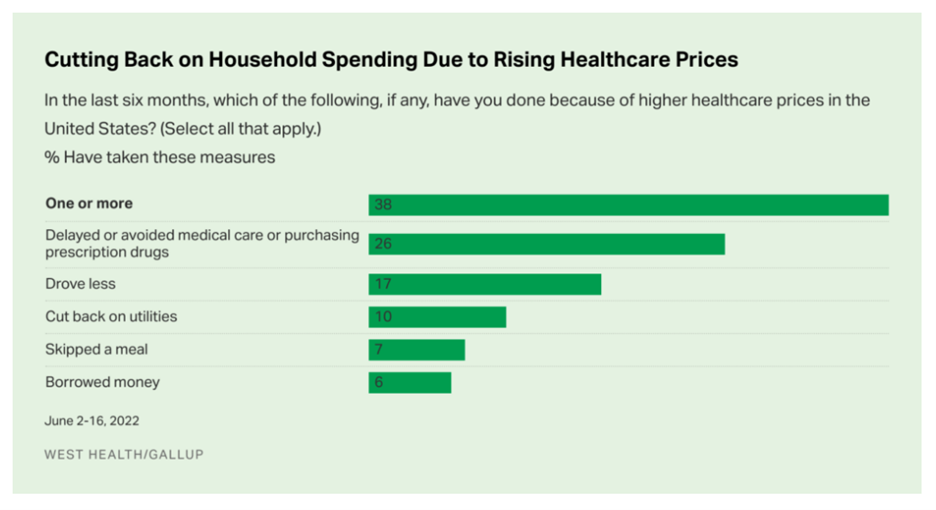

From the patient-as-health-consumer’s standpoint, doing-more-with-less means self-rationing care away from hospitals and providers to doing more DIY and self-care at home and in lower-cost settings. We have seen evidence of this in a Gallup-West Health poll in August 2022, finding consumers avoiding care due to general household inflation (gas, food, energy).

For patients, consumers, caregivers — health citizens, all — health care spending is bound up in the entire household wallet, competing with basic needs especially tight in inflationary 2022.

For health care incumbents, it’s a walking-and-chewing-gum challenge to deal with both the growing supply side of competitors as well as the consumer/patient demand side.

On the supply side, providers and plans will be faced with organizations positioning with technology infrastructure investments, retail service design chops, and price competition, along with brand equity and loyalty that have eluded traditional health care players.

Consumers will be facing greater medical price inflation in 2023 for health insurance plans, based on the latest forecast from WTW.

The XY supply demand curve shown above from Trilliant’s analysis illustrates a government price ceiling shock to health care pricing.

In addition to that possibility (which we may see on certain prescription drug prices, for example), there will also be market-based price competition that will further reduce revenues to providers. Those that cannot scale, coupled with delivering consumer-facing benefits that patients-as-payors appreciate (such as high service levels, empathy, privacy-by-design), could see their current difficult prospects further erode.

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming  Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters

Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters  For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,