Most Americans are healthcare cost-conscious, concerned about various kinds of healthcare expenses, data from McKinsey’s research has found presented in Healthcare consumerism 2018: An update on the journey.

McKinsey’s consumer research identified four themes: affordability as a pressing consumer concern; lack of continuity of care for many consumers; growing demand for digital convenience and access; and, greater willingness to partake in health care programs that lower costs, if made available.

Personal and household concerns about healthcare costs is top-of-mind for U.S. consumers, as I’ve pointed out in previous studies such as Kaiser Family Foundation’s look at top “pocketbook issues,” here on Health Populi. Even for folks earning over $90K a year, KFF found, healthcare costs rank #1 in kitchen table worries ahead of mortgage and rent, or covering utilities, just as they do for people earning much less income each year.

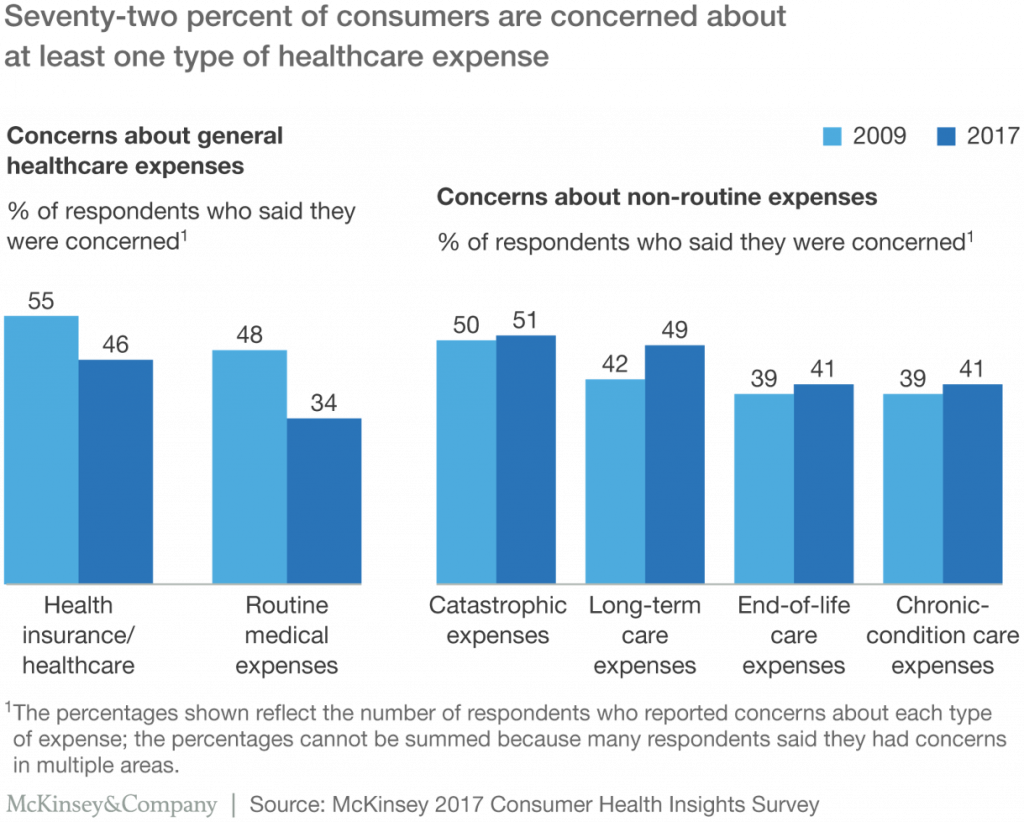

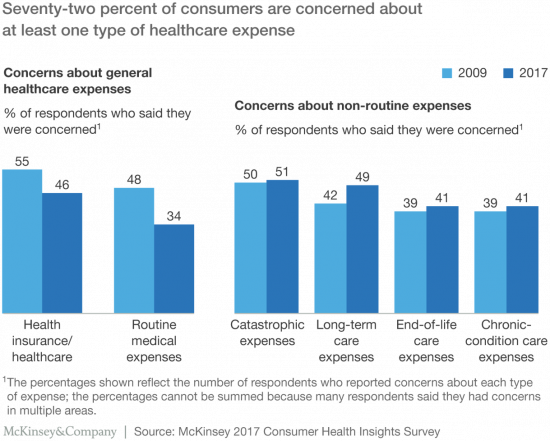

The first chart shows consumers’ concerns about health care expenses over time, comparing perceptions in 2009 and 2017. By 2017, just under one-half of Americans were concerned about healthcare and health insurance costs, and 34% concerned about routing medical expenses. At least 40% of people were concerned about possibly incurring expenses for catastrophic events, long-term care, end-of-life and chronic conditions.

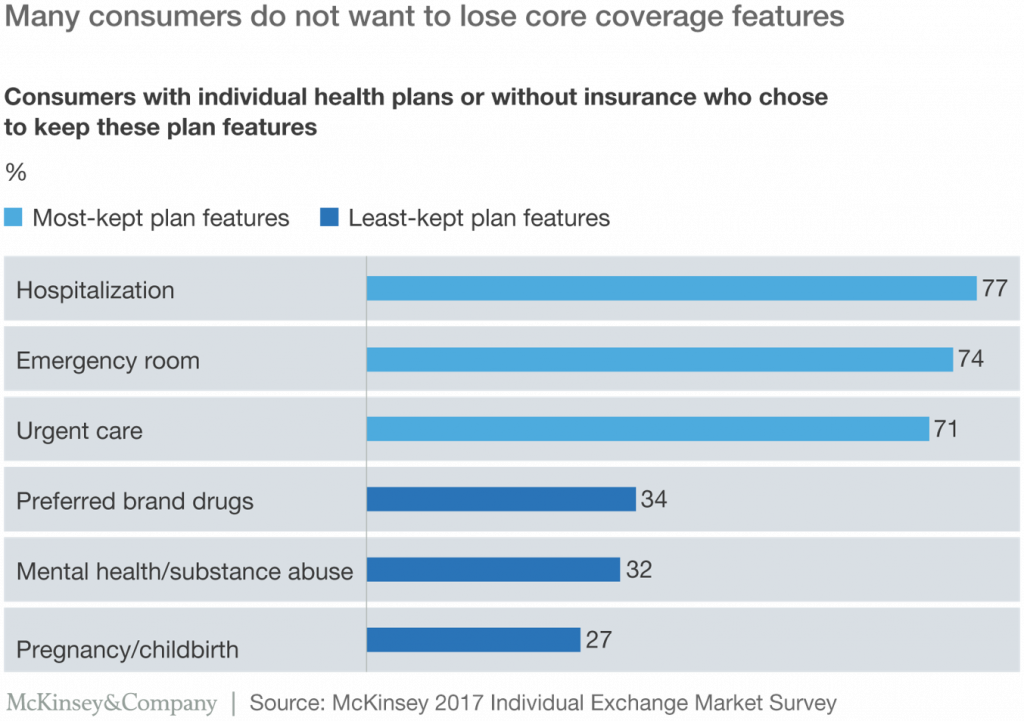

This has resulted in people worrying about losing coverage features like hospitalization (the most expensive cost-component in U.S. healthcare), emergency room, and urgent care. Fully one-third of Americans are also concerned about losing access to preferred brand drugs and mental health services, details shown in the second bar chart.

As patients take on great financial burden for covering health care costs, they seek more accessible and convenient channels for care. So the McKinsey data shows that retail clinic use is steadily growing, especially interests to access immunizations and vaccines, minor illnesses, lab tests, and preventive services.

As part of this growing health-consumer ethos, people are open to digital healthcare solutions. McKinsey found that about 70% of Americans are interested in digital solutions to shop for a health plan, find a doctor, check their health information, monitor health metrics, pay bills, and order prescription drugs.

Based on their growing role as payors, Americans are open to changing health behaviors in exchange for reducing heatlhcare costs. For example, two-thirds of consumers say they’d be interested in achieving 5,000 steps a day per month for a $10/month reduction in a health insurance premium; over one-half of people would go to the gym 2 or 3 times a week for a $15-30/month reduction in a premium; and two-thirds of people would work with a dietitian for weight management.

The bottom line of the report is that, “collaboration with consumer is crucial for controlling healthcare spending.” As a health economist keen on the Triple/Quadruple Aim, I’ve been pointing this out for many years, this from a 2012 Health Populi post — there’s no bending the health care cost curve without the involvement of the central player in healthcare — that is, the patient.

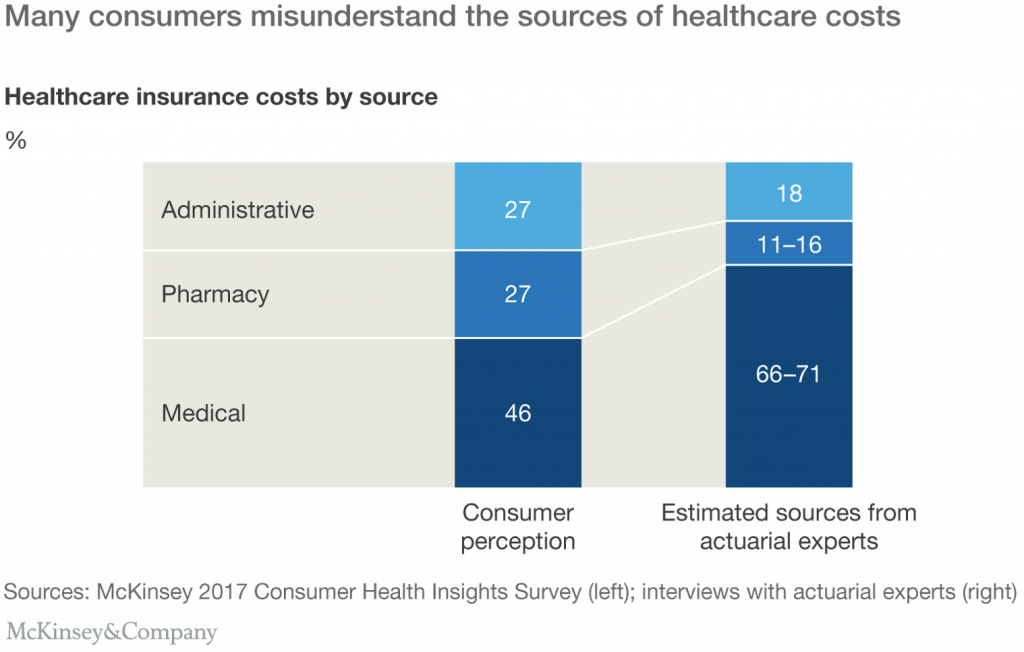

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Returning to the Kaiser Family Foundation poll cited earlier in this post, I point you to the third chart illustrating Americans’ perceptions of health are cost burden assisting prescription drugs/pharmacy, medical care services, and administration. Note that consumers over-index/-estimate the component of prescription drugs versus medical care, the latter of which comprises a much larger proportion of overall health c

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Returning to the Kaiser Family Foundation poll cited earlier in this post, I point you to the third chart illustrating Americans’ perceptions of health are cost burden assisting prescription drugs/pharmacy, medical care services, and administration. Note that consumers over-index/-estimate the component of prescription drugs versus medical care, the latter of which comprises a much larger proportion of overall health c

are spending.

The perception that pharmacy costs comprise a much larger share of spending is due to the fact that consumers feel greater exposure at retail to those costs, and a huge lack of trust with the pharma industry overall that was uncovered in the Edelman Trust Barometer earlier this year (see here in Health Populi for that discussion).

Of course, the bigger health care spend is with medical services — particularly inpatient hospital costs. Americans, who spend more of the national GDP on healthcare than any nation of the world, need a good lesson in health economics to, first, enlight

en people on this data point. At the same time, patients-as-health-consumer need to appreciate the concept of “right-sizing” health care treatment. More behavioral economics baked into health benefit design will nudge patients-as-consumers to see lower-cost care, as appropriate, as some folks have already begun to do by shifting their locus of care for urgent needs from the ER to the urgent care or retail clinic, as McKinsey and others have observed over time.

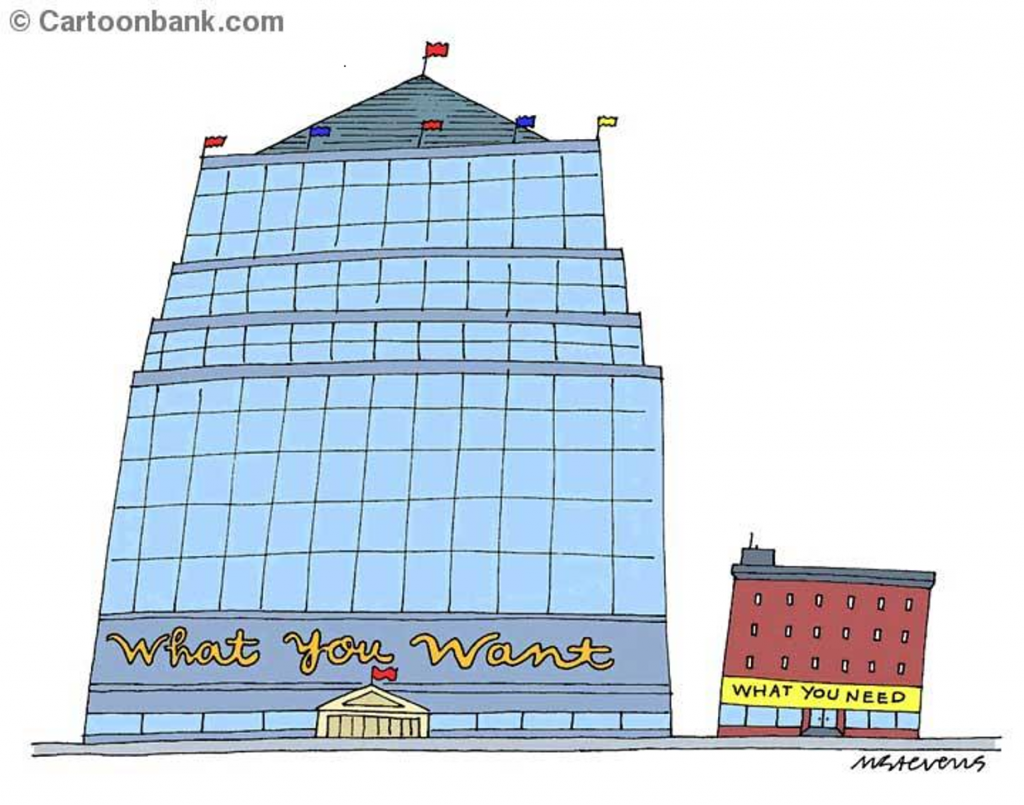

Ultimately, more care is not better care, as this classic New Yorker cartoon teaches us. For more on that, I prescribe reading Shannon Brownlee’s classic analysis, Overtreated.

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming  Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters

Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters  For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,