People in the U.S. are growing their health IT muscles and literacy, accelerated in the coronavirus pandemic. In particular, health consumers in America want more access to their personal health data, a study from the Pew Research Center has found in Americans Want Federal Government to Make Sharing Electronic Health Data Easier.

People in the U.S. are growing their health IT muscles and literacy, accelerated in the coronavirus pandemic. In particular, health consumers in America want more access to their personal health data, a study from the Pew Research Center has found in Americans Want Federal Government to Make Sharing Electronic Health Data Easier.

Pew collaborated with Public Opinion Strategies and Hart Research to conduct a survey in June and July 2020 among 1,213 U.S. adults 18 and over to determine peoples’ perspectives on personal health information in light of their pandemic era experiences.

This study re-confirms the current state of the health consumer who has a “concerned embrace” of technology. I called this out in my 2019 book, HealthConsuming: from health consumer to health citizen.

The COVID-19 crisis has bolstered peoples’ concerned embrace of tech: in the pandemic, more consumers have lost confidence in sharing data with both government and Big Tech.

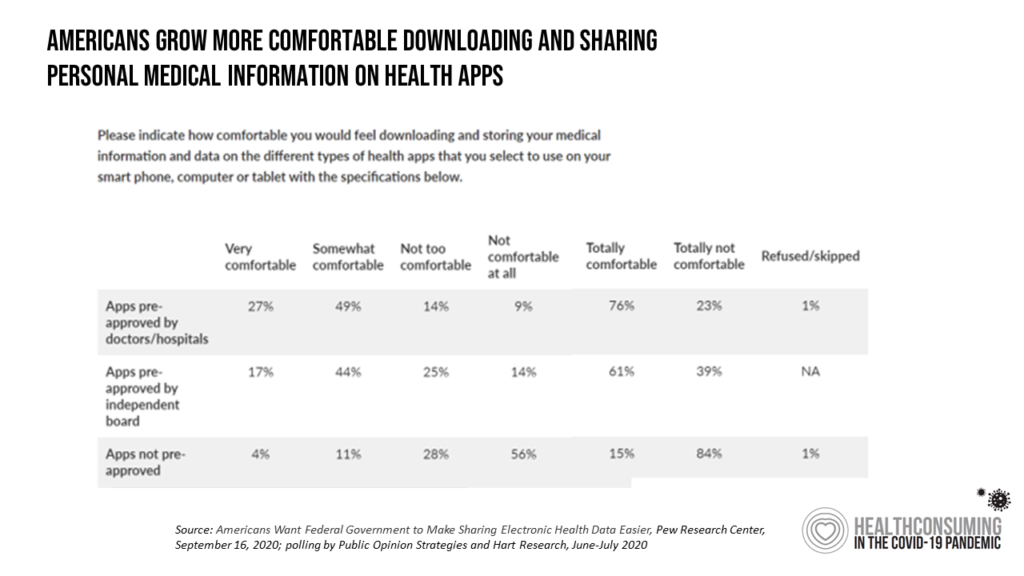

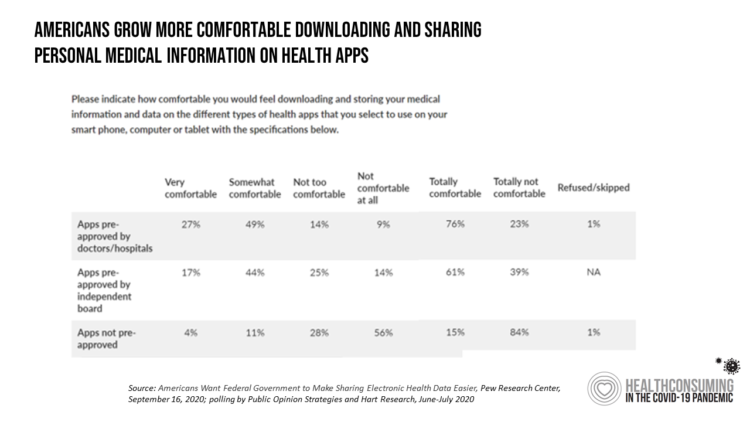

In the Pew survey, 3 in 4 consumers re comfortable sharing their personal health information with apps pre-approved by doctors and hospitals, consistent with the general trust of health care providers as trusted data stewards.

More younger people would be interested in downloading personal health records compared with older people. Still, over 50% of consumers ages 56 to 74 would like to download their EHR data.

The “concerned” aspect of the tech-embrace in health care means consumers are also keen to have privacy data protections and procedures in place to prevent their PHI from traveling outside of trusted health care circles. This is particularly concerning when personal health data is downloaded to an app that may fall out of the protection of HIPAA. Without confidence in the privacy of security of the download site and party, consumers would more likely hesitate in sharing data.

And in the coronavirus pandemic, consumers’ withholding data compromises a community’s ability to manage the spread of infection and “crush” the virus.

The need to inspire trust in sharing personal data in and beyond medical information is becoming increasingly critical in the growing internet-of-things era for health care, from Alexa-skills in voice technology to wearable tech and remote health monitoring shifting care to our homes (see here for more on the home as health hub).

Most consumers understand that data-sharing between health care providers yields value, and support enabling different providers to share personal health information between EHR systems. Over two-thirds of consumers in the Pew study said they would want their different providers (doctors, hospitals, and other clinicians) to share all kinds of information about them including advanced care plans and end-of-life wishes, family medical histories, and other very personal data.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Earlier this year, Accenture found that U.S. consumers’ adoption of digital health technology stalled. One of the driving forces was found to be privacy concerns about health data protections.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Earlier this year, Accenture found that U.S. consumers’ adoption of digital health technology stalled. One of the driving forces was found to be privacy concerns about health data protections.

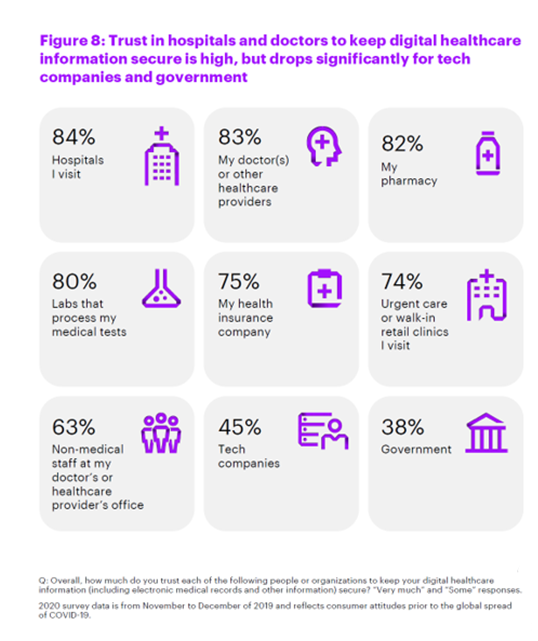

This chart comes from Accenture’s study, illustrating high trust in health care stakeholders — hospitals, doctors, pharmacies, and labs — compared with lower percentages of people trusting tech companies and government agencies to keep personal digital health information secure.

I identified four pillars of health citizenship in my latest book, Health Citizenship: How a virus opened hearts and minds, one of which is “digital citizenship.”

The coronavirus pandemic has shown U.S. health consumers the importance of personal health data as an asset — that is both a personal one and, in aggregate mashed up with fellow health citizens’ data — a public health asset.

That speaks to the accelerated need for a contemporary privacy law that covers a broader group of stakeholders beyond the legacy health care system, in this post-HIPAA era where our digital dust gets generated through our smartphones, apps, retail receipts and credit cards, and social network check-ins. Something akin to an American-style GDPR or national version of the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) would address this need for American digital health citizens.

But the eroding trust people feel compromises health consumers’ buy-in to sharing personal health information. That brings us to another of the four health citizenship pillars: trust.

Trust is in short supply in the U.S. in the current climate: trust in science, trust in government, and trust in each other is in short supply.

Part of re-building U.S. health care better will require recognizing the trust component that was lost even before the pandemic and exacerbated during the public health crisis. In adopting consumer-centered design for health care technology, digging into consumers’ trust barriers and addressing them through privacy-by-design principles will help foster digital health adoption among health citizens. That won’t solve all of the huge trust chasm in America but will help out to nudge the digital health adoption challenge.

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming  Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters

Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters  For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,