A time-and-technology challenged FDA, proliferation of software-controlled medical devices in and outside of hospitals, and growth of hackers have resulted in medical technology that’s riddled with malware. Furthermore, lack of security built into the devices makes them ripe for hacking and malfeasance.

A time-and-technology challenged FDA, proliferation of software-controlled medical devices in and outside of hospitals, and growth of hackers have resulted in medical technology that’s riddled with malware. Furthermore, lack of security built into the devices makes them ripe for hacking and malfeasance.

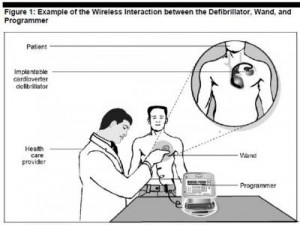

Scenario: a famous figure (say, a politician with an implantable defibrillator or young rock star with an insulin pump) becomes targeted by a hacker, who industriously virtually works his way into the ICD’s software and delivers the man a shock so strong it’s akin to electrocution.

Got the picture?

Welcome to the dark side of health IT and connected health. Without strong and consistently adopted security technology and policies, this scenario isn’t a wild card: it’s in the realm of possibility. This is not new-news: back in 2008, a research team figured out how to program a common pacemaker-defibrillator to transmit a “deadly 830-volt jolt,” according to Barnaby Jack, a security expert.

I had a sobering chat today with Christine Sublett, a privacy and security consultant who works with health industry stakeholders on these issues. She pointed me to the recent report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) called FDA Should Expand Its Consideration of Information Security for Certain Types of Devices. She told me about several cases where some of the most prestigious hospitals in the U.S. have medical equipment that are infected with innumerable computer viruses because, due to FDA regulation of the devices as installed, are unable to update computer security programs per the manufacturers’ directives. According to Pierluigi Paganini, cyber-security expert, other vulnerabilities include:

- Limited battery capacity

- Remote access

- Continuous use of wireless communication

- Susceptibility to electromagnetic (e.g., cellular) or other types of unintentional interference.

- Limited or nonexistent authentication process (such as requiring a password) and authorization procedures

- Disabling of warning mechanisms

- Design based on older technologies

- Inability to update or install security patches.

The GAO found that the FDA’s focus has been on the safety of medical devices — not the security of them. Barnaby Jack believes the FDA doesn’t have the expertise to conduct security audits for every single medical device.

The GAO has analyzed risks from “unintentional threats” (e.g., airport security systems). However, the FDA hasn’t assessed “intentional threats” from adventurous hackers. The FDA categories unintentional threats in three types: via,

- Unauthorized access, when someone directly hacks into a device to alter a signal (as envisioned above in that ICD-implanted politician)

- Malware, when a malicious software program is embedded into a device

- Denial-of-service attack, when, say, worms or a virus overwhelm the device making it unusable.

On industry’s side of this ledger, it can cost lots of money and years of time to incorporate security into a device that’s been FDA-approved, plus additional time-to-market.

More coverage on this issue can be found in the following media outlets:

Wireless Medical Devices Vulnerable to Hacking, TIME

Computer Viruses Are Rampant on Medical Devices in Hospitals, Technology Review

Health Populi’s Hot Points: With the proliferation of medical devices, and the emergence of mobile platforms and sensors in health, this issue will only grow exponentially as a risk to be managed in health care. With the advent of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), institutions thought security could be a challenge. The issue of security for software-enabled medical devices, with technology going mobile both in provider settings and to patients’ homes, makes HIPAA security seem like a proverbial walk in the park.

Here’s an example where the FDA must find a way to deal with this challenge immediately: to give industry and providers crystal-clear guidance on this issue that’s absolutely an accident waiting to happen.

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming  Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters

Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters  For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,