Among all the world’s health citizens, there’s one nation over all that’s most likely to postpone health care due to cost: Americans.

Among all the world’s health citizens, there’s one nation over all that’s most likely to postpone health care due to cost: Americans.

The Commonwealth Fund has surveyed the people of 11 nations to ascertain How Health Insurance Design Affects Access To Care And Costs By Income, In Eleven Countries. That’s the title of their analysis in Health Affairs, published online November 18, 2010.

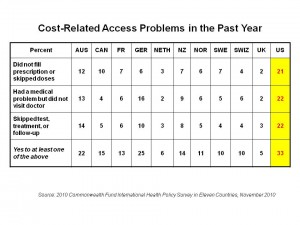

The U.S. spends far more per capita on health care than any of these nations, as well as much more as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) on health. However, as the chart shows, more money/spending doesn’t equate to better access for health citizens. In the U.S., 1 in 5 adults didn’t fill prescriptions or skipped doses, had medical issues but did not see a doctor, or skipped tests/treatments or followed up with a doctor — all related to cost or access challenges. In Norway, France, and Switzerland, the 3 nations spending the next most money on health on a per capita basis, these access issues drop to 1 in 10 adults overall. For New Zealanders and Britons, with the lowest per capita health spending, these three cost/access problems are equally low (for NZ) and virtually nil for the UK.

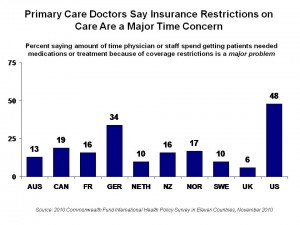

Insurance complexity, health service coordination, and problems with health insurance are also highest in the U.S. Not only are American patients hassled by the system, though; nearly one-half of American physicians say that getting patients needed medications or treatment because of coverage restrictions is a “major problem.”

Insurance complexity, health service coordination, and problems with health insurance are also highest in the U.S. Not only are American patients hassled by the system, though; nearly one-half of American physicians say that getting patients needed medications or treatment because of coverage restrictions is a “major problem.”

One aspect is pretty universal among the 11 health systems: that the lower income you have, the more problems you experience in paying medical bills. While this is most acute in the U.S., in virtually every other country a below-average income negatively impacts peoples’ abilities to pay medical bills in the past year more than for people with above-average incomes — even in countries like Canada, with its single-payer system, and France, where 13% of people with below-average incomes said they had problems paying medical bills compared to 2% with above-average incomes. As the paper bluntly states, “Poorer adults are more likely to need health care and less likely to have the resources to afford it on their own.”

Similarly, people with lower incomes have more trouble getting after-hours care in virtually every nation surveyed; the differentials were greatest in the U.S., between higher and lower incomes (with a spread of 13 percentage points, where 55″% of people with above-average incomes said they had difficulty getting after-hours care vs. 68% of people with lower incomes); Canada (with a spread of 8 percentage points between more vs. less affluent); 13 points in the Netherlands; 12 points in Norway; and, 16 percentage points in the UK (where private sector health care plans are more prevalent among wealthier Brits).

Health confidence, then, is also compromised among health citizens in all countries surveyed for people with below-average incomes. In the U.S., 82% of Americans with above-average incomes are confident they’ll receive the most-effective treatment if they’re sick; only 65% of Americans with below-average incomes are confident they’ll get the most-effective care. This relationship holds across all countries, although the “care-confidence gap” isn’t as dramatic in any other country: the next greatest chasm after the U.S. between richer vs. poorer is in Sweden, with a 12 percent differential (70% of Swedes with above-average income versus 58% of Swedes with below-average income). The most health-confident nation is the UK, with 95% of the wealthier and 92% of those with lower incomes confident — a virtual tie. Similarly, the Swiss have the second-highest proportion of health confident people among 11 nations polled.

The Commonwealth Fund conducted the survey of health citizens via telephone between March and June 2010, among adults 18 and over in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

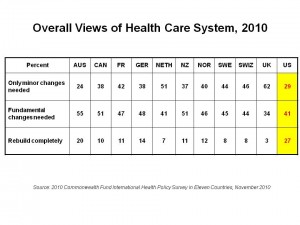

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Among the world’s eleven health citizens polled by The Fund, one tends to seek “complete rebuilding” more than the other ten: Americans, 27% of whom believe in such tabula rasa for the American health system. Another 41% of Americans seek “fundamental changes” to the health system, leaving only 29% who see that only “minor changes” are needed.

Having said that, majorities in most of the remaining ten countries tend to favor fundamental changes or complete rebuilds: only the UK (with 62% wanting only minor changes), and the Netherlands (with 51% seeking only minor changes) have majorities that seem relatively satisfied with their health systems.

The latest Kaiser Health Tracking Poll taken among U.S. health citizens following the mid-term elections in November 2010 indicated inconsistent and relatively unenthusiastic support for health reform as it’s been codified in the Affordable Care Act. Nearly one-half of people who voted in the election would like to repeal the law, Kaiser Family Foundation learned. The American electorate is as split and fragmented about how they’d re-imagine the U.S. health system as the system is split and fragmented itself. In the meantime, as health costs continue to rise for the foreseeable future, the chasm between wealthy and poor Americans, and the related cost-access challenges, will widen.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for