On this day celebrating Martin Luther King, Jr., I post a photo of him in Detroit in 1963, giving a preliminary version of his “I Have a Dream” speech he would give two months later in Washington, DC.

As I meditate on MLK, I think about health equity. By now, most rational Americans know the score on the nation’s collective health status compared to other developed countries: suffice it to say, We’re Not #1.

But underneath that statistic is a further sad state of health affairs: that people of color in the U.S. have lower quality of health than white people do:

- Black women have higher breast cancer death rates than White women

- Asian women are less likely than White women to receive a pap smear

- Hispanic women are more likely than non-Hispanic White women to be diagnosed with cervical cancer at an advanced stage

- Rates of hospital admissions for uncontrolled diabetes are higher for Black women than for women in other racial/ethnic groups

- The rate of hospital admissions for lower extremity amputations due to uncontrolled diabetes is higher for Black women than White women

- The rate of new AIDS cases is higher for Black and Hispanic women than for non-Hispanic White women. Black and Hispanic men had even higher rates than women, as well as higher rates than non-Hispanic White men

- Black women receive treatment for depression less frequently than White women and Hispanic women received treatment less frequently than non-Hispanic White women

- Hispanic women received treatment for substance abuse less frequently than non-Hispanic White women.

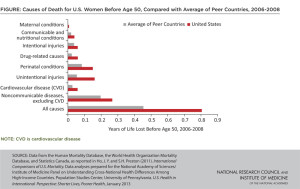

If these statistics don’t move you, then here’s a new-new finding from the National Academy of Science’s latest research, Shorter Lives, Poorer Health, that might surprise you: today, people in the U.S. under 50 have poorer health outcomes than our cohorts in other developed countries. The bar chart illustrates that for women under 50, we’d rather live in other industrialized countries where fewer women under 50 die from noncommunicable diseases, heart disease, injuries, perinatal conditions, drug-related causes, and communicable and nutritional conditions.

Yes, more younger women in the U.S. — the wealthiest nation in the world — lose more life-years due to malnutrition, infectious disease, injury, and lifestyle-borne diseases like diabetes and heart disease than in our fellow rich countries.

Read what U.S. doctors have to say about this challenge in JAMA (free access for this article). Top line for doctors lies in the concluding sentence: “Apart from the human and economic consequences affecting today’s adults and workforce, the health disadvantages faced by today’s children carry profound implications for tomorrow’s adults, the nation’s economy, and national security. Now the question is what US society is prepared to do about it.”

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I am a child of metro Detroit, growing up in the 1960s and 1970s. As a very little girl, I lived through the Detroit Riots of 1967, the day after which my father drove us through the fire-devastated neighborhoods of his friends and clients who lived and worked around 12th Street and Grand River. It was a visceral moment for me in my life, one of my earliest memories, seeing burned-out shops on pedestrian main streets. I remember still the smoky smell which imbued my young lungs. I wondered why something like this happens.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I am a child of metro Detroit, growing up in the 1960s and 1970s. As a very little girl, I lived through the Detroit Riots of 1967, the day after which my father drove us through the fire-devastated neighborhoods of his friends and clients who lived and worked around 12th Street and Grand River. It was a visceral moment for me in my life, one of my earliest memories, seeing burned-out shops on pedestrian main streets. I remember still the smoky smell which imbued my young lungs. I wondered why something like this happens.

In a few years’ time, I was reading Martin Luther King’s book, Why We Can’t Wait; The Autobiography of Malcolm X, and Native Son by Richard Wright — still, one of my favorite books. In college, I delved deeply into urban economics and urban planning, soaking in Jane Jacobs book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, among other influential books on the syllabus.

At the University of Michigan School of Public Health, I then learned to connect the dots between our environment, our socioeconomic status — especially the role of education — and health.

Addressing health disparities is as much about access to health insurance as it is to access to good and well-priced food, safe schools, education, good jobs, and sound social policies about gun ownership and use.

These interrelationships are fundamental to public health thinking. Those of us whose work touches any aspect of health and health care must attend to public health and commit to reducing health disparities in America. A healthy populace is a more productive populace across so many dimensions. As we continue the hard work to re-build the national economy, public health should and must be seen and used as a pillar for economic growth.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for