In the U.S., we’ll be the #1 oil producer by 2020. We’re the largest national economy in the world (to be surpassed by China before 2030). And, we’re #1 in terms of the lowest taxes paid as a percentage of national GDP. That’s all heartening news for the time being.

In the U.S., we’ll be the #1 oil producer by 2020. We’re the largest national economy in the world (to be surpassed by China before 2030). And, we’re #1 in terms of the lowest taxes paid as a percentage of national GDP. That’s all heartening news for the time being.

But we’re also #1 in what I’ll call “un-health:” in auto accident mortality for adolescents, obesity rates, infant mortality, prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases, and among other public health metrics.

A report from the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (NRC/IOM) calls out what JAMA terms The US Health Disadvantage: that America is the most affluent nation on earth, with a citizenry whose health profile ranks at the bottom for most health indicators compared with peer developed nations.

Why is this the case? Woolf and Aron argue in JAMA that the following factors contribute to poor health outcomes in America versus peer countries:

- Lack of universal health insurance coverage

- A weaker primary care infrastructure

- Greater barriers to people accessing health care

- Fragmented care delivery with poor care coordination

- More visits to the ER per capita

- Mis-communication between doctors and patients.

Those fall into the institutional/provider and policy side of the equation. On the consumer-health citizen-patient side, there are contributing factors, as well:

- More calories consumed per capita

- Greater likelihood to abuse illicit drugs

- Less likelihood to fasten seat belts in cars

- Greater ownership of firearms

- Less propensity for young people to practice safe sex

- Larger socioeconomic disparity between wealthy and poor Americans.

On this last point, it’s important to note that a large portion of affluent Americans have less than optimal health outcomes based on lifestyle factors and social values.

The authors assert that “public support is necessary to propel” efforts for bolstering public health, but recognize that there is scant public awareness of these low American health rankings. “Fewer understand that Americans are sicker and die younger than people in other wealthy nations,” they note.

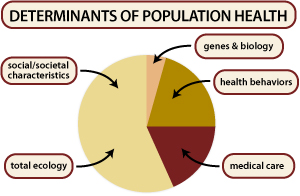

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The JAMA piece is wise to delineate the two sides of the public health equation: the institutional/public policy inputs, along with the public’s contribution to the poor health outcomes crisis in America. Personal health behaviors have a substantial impact on public health: see the chart for relative values for social/societal traits (e.g., socioeconomic status, education) versus biology and genes (relatively small) versus the health system (medical care). Personal health behaviors have a greater impact than genes or medical care.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The JAMA piece is wise to delineate the two sides of the public health equation: the institutional/public policy inputs, along with the public’s contribution to the poor health outcomes crisis in America. Personal health behaviors have a substantial impact on public health: see the chart for relative values for social/societal traits (e.g., socioeconomic status, education) versus biology and genes (relatively small) versus the health system (medical care). Personal health behaviors have a greater impact than genes or medical care.

This is why health engagement is so central to the larger discussion of the health economy. Regardless of the form health reform takes in the U.S. – that other side of the equation – personal responsibility for one’s health, and the health of our loved ones, impacts our kitchen table and household budgets. But we, individually and connected-ly, also have the power to shape public health and the national economy.

For more on the Shorter Lives, Poorer Health report, read my take in Health Populi on Martin Luther King Day, 2013.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for