The American health infrastructure is not First World or First Rate, based on the outcomes.

The American health infrastructure is not First World or First Rate, based on the outcomes.

This, despite spending more on health care per-person than any country on the planet.

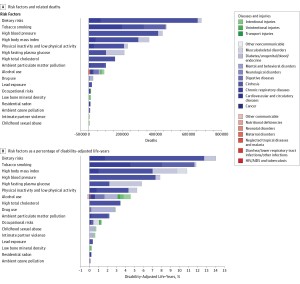

Two seminal reports are out this week reminding Americans that our return-on-investment in health spending is poor. The first research comes from JAMA titled The State of US Health, 1990-2010: Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors. There is some good news in this report at the top line: that life expectancy for Americans increased in the two decades from 75.2 years to 78.2 years. But this positive quantitative outcome comes with some qualitative caveats that sober us from feeling like Pollyanna’s about the U.S. health system:

- Among the 34 developed countries (in the OECD), America’s rank for death rate fell from 18th to 27th.

- Morbidity and chronic disability account for nearly half of the U.S. health burden.

- Improvements in population health in the U.S. “have not kept pace with advances in population health in other wealthy nations,” the report concludes.

The authors of the report – dozens of physicians, doctorates, master’s prepared professionals in public health, affiliated with major medical schools and universities from the U.S. and abroad — recommend that “the best investments for improving population health would likely be public health programs and multisectorial action to address risks such as physical inactivity, diet, ambient particulate pollution, and alcohol and tobacco consumption.”

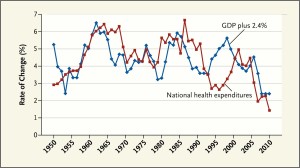

The second paper, written by godfather of health economics Victor Fuchs, is published in the July 11, 2013 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. In The Gross Domestic Product and Health Care Spending Fuchs analyzes U.S. health spending between 1950 and 2010, finding that there is, generally, a direct relationship between the growth of the GDP (national ecoonomy) and health spending.

The second paper, written by godfather of health economics Victor Fuchs, is published in the July 11, 2013 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. In The Gross Domestic Product and Health Care Spending Fuchs analyzes U.S. health spending between 1950 and 2010, finding that there is, generally, a direct relationship between the growth of the GDP (national ecoonomy) and health spending.

The big exception happened in the mid-1990s when growth of national health spending slowed below 3% per year although GDP grew. Fuchs reminds us the health economics history lesson that at this point, managed care was growing and eventually patients and providers lashed back at restrictions of choice.

Fuchs points to the most recent slow-down in the rate of health spending growth, which analysts have largely attributed to the recession. However, Fuchs notes that other factors, such as the large swing toward patented prescription drugs going generic, and the fall in hospital readmissions, are one-time gains that won’t sustain slowing health care costs in the longer run.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Recently, my husband took 3 meetings in one day in Germany: in the morning, he started in the northern sector of the country, then took a train to a city hundreds of miles from there. He had lunch with a client in that town, then hopped onto a second train to get to the southern part of Germany to take a third meeting in a Bavarian town, where he enjoyed dinner with another client. That’s 3 meetings in 3 far–flung towns in one day in one of the (geographically) largest nations in Europe.

What enabled that to happen was a strategic choice that Germany made: to make a major investment in transportation infrastructure that would benefit the nation’s economy and people.

For several decades, Americans and our legislators haven’t had a genuine, collective conversation on how to best invest in America’s public health as an infrastructure investment.

In introducing his paper, Fuchs asks, “How much will the United States s[end on health care during the next decade or two?” He responds that the answer will determine the extent of care physicians can provide to patients and how much the U.S. can spend on other categories — the Guns vs. Butter debate, and under “Butter,” how much can be spent on education, transportation, city planning, food systems, new energy sources, and so on.

Taken together, these papers remind us that spending on “health” spans more than health “care,” that public health writ large has at least as much to do with the social determinants of health as access to health services like hospitals and visits to doctors. This calls for a broadening of U.S. policymakers’ mindsets on how to define “health.” While the Affordable Care Act nods to prevention and primary care, it doesn’t go nearly far enough into the aspects of health reform that can impact, at scale, public health to move Americans above position #27 in the world’s mortality table.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for