There are thousands of downloadable apps that people can use that touch on health. But among the 40,000+ mobile health apps available in iTunes, which most effectively drive health and efficient care?

There are thousands of downloadable apps that people can use that touch on health. But among the 40,000+ mobile health apps available in iTunes, which most effectively drive health and efficient care?

To answer that question, the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics analyzed 43,689 health, fitness and medical apps in the Apple iTunes store as of June 2013. These split into what IMS categorized as 23,682 “genuine” health care apps, and 20,007 falling into miscellaneous categories such as product-specific apps, fashion and beauty, fertility, veterinary, and apps with “gimmicks” (IMS’s word) with no obvious health benefit.

Among the 23,682 so-called genuine health apps, about 2/3 focus on consumer use and 1/3 on health care providers.

The bottom-line: there’s no base of evidence that mobile health apps deliver clinical value in health outcomes or support and sustain health behavior change.

IMS found that, in health:

- Few apps focus on managing chronic disease for the highest health-spenders, who tend to be older

- 5 apps account for 15% of downloads

- Most apps have been downloaded fewer than 500 times

- There’s currently little guidance from physicians on health apps, largely because

- Evidence is scant supporting which tools yield clinical benefit.

Health apps provide several functions: they inform via text, photo and video; they instruct; they record, capturing user’s data; they display data; they guide or diagnose; they remind and alert the user (say, to take a medication or test blood); and, they communicate to social networks or health providers. Providing information is the most common function across the health apps: while two-thirds can display information, one-half provide instructions, and only one-fifth track or capture user’s data.

App categories include:

- Healthy living, promoting modifiable health risk factors such as healthy weight, smoking cessation, and exercise. The most popular apps in this category are the Calorie Counter and Diet Tracker from MyFitnessPal, the Calorie Counter PRO by MyNetDiary, the Chest Trainer from Fitness Buddy, Cycle Tracker Pro, Quit It 3.0 to stop smoking, and Quit Smoking Now HD hypnotherapy with Max Kirsten.

- Self-diagnosis, which the FDA intends to regulate per its September 25, 2013, guidance. The top apps in this category were HealthTap, iTriage, and WebMD.

- Filling prescriptions, via pharmacy apps. Top apps were GoodRx, MyRefill Rx, and Walgreens.

- Medication compliance, helping patients stick to prescribed dosing regimens. Top apps were Dosecast, Pill Monitor, and RemindMe Prescription.

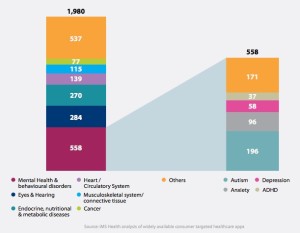

By therapy area, IMS found mental health and behavioral disorders, eyes and hearing, endocrine and nutrition, heart/circulatory, musculoskeletal, and cancer to be the most prevalent areas apps cover. Within mental and behavioral health, autism, anxiety, depression, and ADHD were covered by a total of 558 apps.

Health apps specifically for seniors are addressed by only 27 apps.

IMS identifies four steps for moving forward:

- Recognition by payers and providers of the role that apps can play in health care

- Security and privacy guidance

- “Systematic” curation and evaluation of apps that provide doctors and patients with summaries that aid decision making for use and “prescription”

- Integration of apps with patient care workflows.

There are roughly 100 “advanced” apps, IMS says, that are FDA-approved but not targeted to consumer use (such as the BlueStar app from WellDoc, which requires a prescription from a health provider).

IMS developed a scoring methodology of 100 points maximum, based on 25 criteria such as the type and quantity of information provided by the app, how the app tracks or captures user data, and the quantity of device capabilities in the app. Condition-management apps that provide some continuity of care and support were more heavily valued than simple communications or reference apps. The mode score was between 21-25 points in 100, achieved by over 2,500 apps.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: “There is a big desert that you enter once you leave the hospital or the doctor’s office,” Dr. Jonathan Birnberg of North Shore University Health System told the IMS researchers. “So that is where I really see a lot of opportunity and personal excitement around using an app as a tool to help fill that space.”

eClinicalWorks earlier this year found that nearly 9 in 10 doctors would be keen to prescribe a mobile health app, supporting Dr. Birnberg’s observation. So the demand side of the equation, in terms of doctors’ support, is heating up for mobile health apps.

The end-user demand factor is the patient, person and caregiver, millions of whom do initial downloads of health apps in both “genuine” categories as defined by IMS and the looser apps that do everything from help one imagine themselves in a thinner body to predicting fertility for the best baby-making moments.

In the interstices are regulators and payers, who in concert with the app developers, are only beginning to establish a dance that’s got, for the first time, some context for a score: that is the FDA regulatory guidance issued in September, which focuses on diagnosis as the area on which the regulator will focus.

So with the regulatory regime getting clearer, it’s reimbursement – who pays for the app – which remains a question. Payment, and professional recommendation/prescription get, traction when evidence builds. For the most popular apps, listed above in the four categories, there is a large group of users who can crowdsource results. On the clinical side, researchers can incorporate apps into remote health monitoring and post-hospital discharge studies in patients self-managing at home. Physicians can recommend apps and track, with their patients, progress for people managing diabetes, kids with asthma tracking medication adherence, and success in quitting smoking.

The very nature of the mobile health app requires collaborative research between patients and the health care system, working together. This is an opportunity to build shared decision making, participatory medicine and community-creation of health.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for