If your wallets are lighter at the end of the month, you’re likely to have less access to quality food, and more likely to be admitted to the hospital if you have diabetes. The hypothesis that people with low incomes whose household budgets are spent before the end of the month have greater health inequities was tested in the article, Exhaustion of Food Budgets At Month’s End And Hospital Admissions For Hypoglycemia, published in the January 2014 issue of Health Affairs.

Researchers from the University of California – San Francisco found that, indeed, the health in households with low-income suffer from a “pay cycle” where incomes are depleted by the end of the month, leading to food risks that can result in hospital admissions for people managing diabetes. This raises policy implications for food subsidies like food stamps and other programs that provide nutritional safety nets beyond the “first day of the month.”

There is evidence that people who are on fixed incomes, like Social Security and assistance for needy families, spend this income earlier in the month: rent and utility bills are paid=for early in the month when they’re due, leaving little disposable money for food by month-end. As a result, this is usually when soup kitchens and food pantries also see increased demand.

Managing hypoglycemia is key for managing the chronic condition of diabetes. In the short term, the researchers explain, hypoglycemia can result in acute symptoms and trauma, and in the longer term, reduced quality of life and increased risk of dementia.

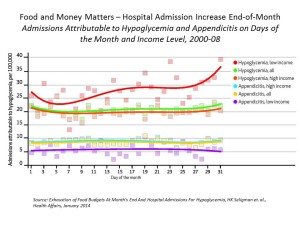

There’s a 27% increase in the rate of admission for hypoglycemia in low-income households in the last week of the month, versus 10% in the second week of the month, this study found. This was statistically significantly greater than for people with higher incomes.

The researchers discuss the role of food budgets in the increase of admissions for hypoglycemia. Going hungry or being at-risk of going hungry has been associated with a two- to three-fold increase in the risk of self-reported severe hypoglycemia, they assert. One solution offered by the researchers is to re-distribute food assistance benefits to people over the course of the month, which has drawbacks in terms of time and expense of transportation back and forth to a food store. Another solution, the authors say, would be to increase the overall payment for food at the start of the month.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: This study connects the dots between food, money, health outcomes, and health disparities for people with very low incomes. This relationship is cyclical and ongoing if it’s not disrupted at the food/money nexus.

In addition to re-thinking how food security gets distributed to people who really need it, health services can also be delivered in more convenient, accessible, and ultimately less expensive modes. For example, the role of the pharmacy on Main Street could be extended to provide primary care and access to a market basket of health foodstuffs. Consider the initiatives of Walgreens to add fresh food to the front of the store. Couple this with medication adherence bolstered by the back-of-the-store in the pharmacy, and you’ve got a model for primary care, everywhere, where people live.

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a