The convergence of technology developments – such as the internet, mobile phone adoption, cloud computing, sensors, electronic health records – with societal evolution including consumerism, demand for transparency, and “flatter” organizations – enable the phenomenon of Connected Health. Connected Health by definition includes mobile health (mHealth), telehealth and telemedicine, as presented in the February 2014 issue of Health Affairs which is dedicated to this theme.

The convergence of technology developments – such as the internet, mobile phone adoption, cloud computing, sensors, electronic health records – with societal evolution including consumerism, demand for transparency, and “flatter” organizations – enable the phenomenon of Connected Health. Connected Health by definition includes mobile health (mHealth), telehealth and telemedicine, as presented in the February 2014 issue of Health Affairs which is dedicated to this theme.

Why Connected Health’s time is Now relates to those factors cited above, and the underlying challenge of managing health care costs. While all nations in the developed world are facing difficult health economies, the U.S. spends so much more and gets so much less from national health spending, which now approaches nearly $1 in every $5 of American GDP.

Several of the papers in this issue demonstrate that connected health can bolster peoples’ health engagement. Health engagement can in turn inspire patient activation, which can then lead to cost-savings in a health plan and community, Dr. Judith Hibbard found and published in Health Affairs exactly one year ago in that issue’s theme of patient engagement.

Among the dozen+ must-read articles is one by three people from whom I’ve personally learned a lot: Wendy Everett, who leads NEHI; Molly Coye, Chief Innovation Office of UCLA Health; and, Dr. Joseph Kvedar, Founder and Director of the Center for Connected Health. Together, they’ve written a primer on the connected health opportunity that succinctly surveys. in 5 pages, the definition of, rationale for, and technologies comprising connected health. The bottom line: “Physician and nurse champions will need to take the lead in ensuring that providers embrace emerging models of care management.” The opportunities of doing so will help to extend provider capacity, expand access to specialty physicians in short-supply, help patients stick to therapies, and reduce waiting times.

A key piece of implementing connected health programs, and one that often derails them before they get going, is building in privacy and security technology, policies and procedures. Joseph Hall and Deven McGraw, both of the Center for Democracy and Technology, explain the risks of the growing use of health sensors, remote health monitoring, and cloud-based health systems when it comes to managing privacy and security to comprehensively cover the telehealth ecosystem. In fact today, No federal agency actually has authority to enact privacy and security requirements in this area, Hall and McGraw warn, which could, at a minimum, undermine peoples’ trust in this innovative way to delivery health care. They argue for the Federal Trade Commission to be “the” single agency to oversee this challenge.

There’s no patient engagement without the consumer’s involvement, so William Frist, former U.S. Senator who co-chairs the Health Project at the Bipartisan Policy Center with Sen. Tom Daschle. (Sen. Frist is also a licensed surgeon whose father founded the Hospital Corporation of America). Frist’s piece in Health Affairs talks about connected health and “the rise of the patient-consumer,” asserting that the biggest driver of health status is a person’s individual behavior. What informs consumerism in health care, Frist writes, is ensuring consumers access to information. He concludes by talking about the hope for health consumer-led transformation, enabled through government incentives like the HITECH Act which is promoting physician adoption of electronic health records and sees health IT as “transformative” in improving health delivery and economics in the U.S.

Other articles in this journal cover deployments and connected health case studies, along with regulatory issues that constrain the growth of telehealth such as patchwork state-by-state regulations, like the licensure of professionals and malpractice liability variations.

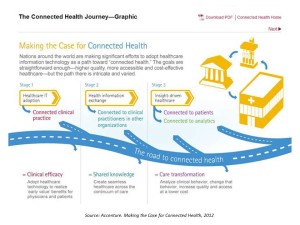

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The graphic is borrowed from Accenture’s report published in January 2012 called Making the Case for Connected Health. That study analyzed research the firm conducted in eight countries (Australia, Canada, England, France, Germany, Singapore, Spain and the U.S.), looking at infrastructural and clinical developments that support the delivery of health via information and communications technologies. These six dynamics included vision and leadership, strategic change management, robust technology infrastructure, co-evolution, clinical change management, and integration driving integration. A key finding was that the U.S. isn’t nearly ahead of the pack when it comes to connected health. A raft of reasons obstruct the innovation of American in connecting health for people and providers, such as fragmented financing; lack of aligned incentives between patients, providers and payors (where clinicians might be responsible for implementing health IT and remote monitoring tech’s, but payors reap the financial benefits); and, clinical workflow challenges that prevent doctors and nurses from adopting and deeply implementing innovations due to (1) organizational inertia and (2) very real day-to-day work patterns that get ingrained in daily processes.

When we talk about Connecting Health, be mindful that the technologies are plentiful, exciting and promising. But it’s not as easy as plugging a blood pressure USB device into a consumer’s at-home computer, or downloading a mobile health app on a smartphone. The heavy lifting happens in changing peoples’ behaviors – and those people include most especially health providers, patients and caregivers. And today, consumers appear more ready to adapt than health providers.

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider

I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider  Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for