A consumer who is faced with greater financial skin-in-the-healthcare game, cost-sharing, is expected to become a smart shopper for lower-priced health products and services.

When it comes to patients given prescriptions for medicines, the theory is that patients will choose less expensive generic drugs over brand names it people think the cheaper meds are good substitutes. This is referred to as the generic-drug dispensing rate (GDR).

But the theory doesn’t consistently hold true in real life, a study from the Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI), Brand-Name and Generic Prescription Drug Use After Adoption of a Full-Replacement, Consumer-Directed Health Plan With a Health Savings Account, finds.

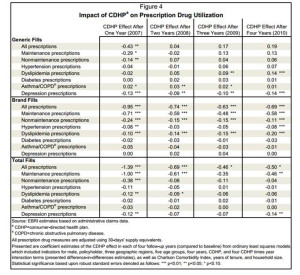

The study analyzed consumers’ use of prescription drugs to treat asthma/COPD, depression, diabetes, dyslipidemia (abnormal amounts of lipids in the blood), and hypertension over a five year period (2006-2010). When consumers moved into a consumer-directed health plan with an HSA, peoples’ “fill rates” for generics were overall lower as a result of the HSA plan. In EBRI’s words, “higher GDRs were largely reached through reductions in utilization” — that is, fewer prescription fills. There were two exceptions: more generic scripts written for cholesterol reducing meds in years 3 and 4, and more generic fills for asthma/COPD in years 2 and 3).

Consumer-directed health plans (CDHPs) are the growing flavor in health insurance in America. These are plans that shift more “skin on the game” — financial burden and responsibility for choice — to consumers enrolled in these plans, through high-deductible health plans coupled with health savings accounts (HSAs).

Health Populi’s Hot Points: EBRI has found that consumers who use HSAs in their health plans often opt-out of spending for prescription drugs – notwithstanding the fact that generics are priced much lower than brand-names on the PBM formulary. That short-term “fiscal” rationale — saving dollars in the short-run — can lead to longer-term, higher medical costs that occur because a patient with diabetes didn’t manager her A1C level, or that chap with COPD didn’t spring for his inhaler and ended up in the emergency room with breathing challenges.

But creating health insurance with some artfulness in the form of value-based insurance design (VBID) can nudge people to fill the prescription for a maintenance medication by dropping or dramatically lowering a copayment amount, or taking maintenance medications entirely out of the deductible by defining them as “preventive,” EBRI notes.

Behavioral economics are useful in inspiring and sustaining behavior change in health care. Here’s an opportunity where that makes so much sense for people managing health conditions amenable to behavior change: depression, diabetes, hypertension and the others included in this study.

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming  Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters

Thank you Team Roche for inviting me to brainstorm patients as health citizens, consumers, payers, and voters  For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,