9 in 10 U.S. adults would be willing to share their personal health information to help researchers better understand a disease or improve care and treatment options — with varying desires to control the anonymity of their data, according to the fourth Makovsky Health/Kelton Survey published April 24, 2014.

This study gauged peoples’ perspectives on personal data privacy based on 1,001 responses from Americans ages 18 and older and was fielded in March 2014.

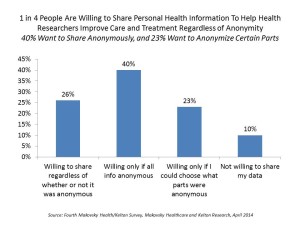

The chart shows four variations on the theme of consumers’ interest in sharing their personal health data with researchers, finding that:

– 40% of people will share only if all of their information is anonymous

– 26% of people will share regardless of anonymity

– 23% will share if they can control some elements of their data

– 10% won’t share regardless of anonymity.

Thus, only 1 in 10 people wouldn’t share their personal health information with researchers under any condition, leaving 90% who would — given certain circumstances.

Under the demographic hood, it’s interesting to note that older people aren’t that much more keen to anonymize their data than younger people (who typically are more open on online social networks). 38% of people 18-34 said they would be willing to share personal health info only if it was all anonymous; 42% of people 60 and over said they’d share only if data were anonymous. Given the study’s 3.1% margin of error, these proportions are very close indeed. People who are parents don’t different that much in their wish for anonymity and sharing versus non-parents.

The study also learned that most consumers (81%) would be interested in adopting a wearable device to track their health. Today, however, only 1 in 10 people use a connected health device based on the Consumer Electronics Association’s information. The most demand for wearables was found for tracking fitness (48%), helping with a personal health issue or disease (41%), tracking diet and nutrition (33%), tracking sleep (29%), and managing stress (27%). More women desired wearable devices for health than men, and many more younger people are keen on wearables for diet and nutrition than people 60 and older.

Makovsky/Kelton looked into how consumers perceive health websites for seeking information. Those people willing to share personal health information are more likely to visit and trust a pharma-sponsored website than other consumers.

Finally, the survey asked people if they have any health apps on their smartphone or tablet. 8% of people have 1 app, 5% have 2 apps, 1% have 3, 1% have 4, and 4% have 5 or more mobile health apps. Thus, taken together, 19% of people say they have at least one mobile app for health. Here, more parents tend to have more health apps than non-parents.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Trust is the precursor for health engagement. This study finds that the majority of people trust researchers working to solve health care challenges – to improve care and innovate new treatment options. The dot-connecting here is that consumers will trade off sharing their personal health information — with provisos on ensuring anonymity for all or some of this information — in exchange for value. In this case, the value proposition is the improvement of health care processes and therapies.

Trust is bolstered when a health professional — a doctor, a nurse, a pharmacist — recommends a website, and most particularly a website sponsored by a drug company. The tiers of source-trust among consumers for visiting a pharma website are a health provider recommendation (55%), a peer recommendation (35%), and a news article (27%).

We’ve entered the data-sharing era of health care, where more consumers are looking to co-create health with the health system, and with their peers. Ensuring trust and privacy at this early stage of this era, when patients and consumers have a large glass of goodwill for sharing-for-good in health care, will be crucial to inform research that improves health care for all.

Thank you, Jared Johnson, for including me on the list of the

Thank you, Jared Johnson, for including me on the list of the  I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a