“For Big Data, Big Questions Remain,” an article by Dawn Falk in the July 2014 issue of Health Affairs, captures the theme of the entire journal this month. That’s because, for every opportunity described in each expert’s view, there are also obstacles, challenges, and wild cards that impede the universal scaling of Big Data in the current U.S. healthcare and policy landscape.

“For Big Data, Big Questions Remain,” an article by Dawn Falk in the July 2014 issue of Health Affairs, captures the theme of the entire journal this month. That’s because, for every opportunity described in each expert’s view, there are also obstacles, challenges, and wild cards that impede the universal scaling of Big Data in the current U.S. healthcare and policy landscape.

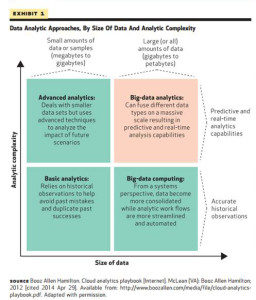

What is Big Data, anyway? It’s a moving target, Falk says: computing power is getting increasingly powerful (a la Moore’s Law), simpler and cheaper. At the same time, the amount of information applicable to health and health care is exploding. As a definition, the “3 V’s” offered in “Creating Value in Health Care Through Big Data: Opportunities and Policy Implications” by Joachim Roski and colleagues (from Booz and Alvarez & Marsal) are useful: Volume, Velocity, and Variety. Big Data means there’s a lot of it (Volume), a lot of different kinds of it (Variety), and the ability to process data in real time to extract the most value out of it (Velocity).

The variety of data is growing especially in terms of information coming from outside of the traditional health system: from people, patients, themselves. And these bits and bytes can be very personal, such as the person’s location, their retail spending (think visits to the Bunny Ranch, fast food lunches, and fast cars bought on credit cards), Google searches, and responses to medication.

The opportunity for using big data to lower the costs of health care in the U.S. is explored in “Big Data in Health Care: Using Analytics to ID and Manage High-Risk and High-Cost Patients” by David Bates et al. This piece analyzes six use cases for lowering costs: high cost patients, readmissions, triage, de-compensation (which is patients’ worsening health), adverse events, and optimizing treatment for people with multiple organ system diseases. Although they analyze data from inpatient settings, Bates and team believe that “Analytics will almost certainly be useful across the health care continuum.” Still, they cite many policy implications: regulatory (such as FDA oversight on health IT and analytics, clinical decision support, and embedded algorithms in medical technology); payment (say, how quickly value-based payment might be adopted, which would encourage broader use of analytics); and, privacy (where there are many thorny issues, from whether HIPAA is broad enough to cover Big Data analytics issues to consumers’ willingness to share data).

Other obstacles to adoption of data analytics are discussed in “The Legal and Ethical Concerns That Arise From Using Complex Predictive Analytics in Health Care” by Glenn Cohen et. al. “The use of predictive analytics, defined as the use of electronic algorithms to forecast future events in real time, make it possible to harness the power of big data to improve the health of patients and lower the cost of health care,” the authors optimistically note. But predictive analytics in health care raises policy, ethical and legal challenges across the continuum of analytics, from initially acquiring the data through to the implementation stage. For example, when acquiring data, patient consent, privacy and fairness and equity issues arise. HIPAA allows for the use of de-identified patient-level data without consent, but re-identification is possible (see the important work of Latanya Sweeney’s Data Privacy Lab at Harvard) and data breaches are, too. Equitable representation in the data population is important, where certain groups of people – say vulnerable high-risk/high-cost patients – could be excluded from care. The authors rightly raise the spectre of Tuskegee in this section of their essay. To deal with equity and fairness, the authors recommend governance structures that include community engagement boards. Other phases of analytics after the initial data collection phase include building and validating the data model and keeping patients at the center; testing the model in real world; and, broader dissemination and adoption of the model. For each of these analytics phases, there are legal and ethical concerns, along with regulatory issues and broad social and consumer conundrums.

Patients’ growing role in generating data outside of the hospital, doctor’s office and lab are explored in several essays. In “Patient-Powered Research Networks (PPRNs) Aim to Improve Patient Care and Health Research” by Rachael L. Fleurence et. al., the authors talk about new technologies that support patient generated data that can populate so-called “patient-powered” research: these include online communities, wearable health devices, smartphone apps, and personal health records. PPRNs can help speed the rate of clinical trial recruitment, and get more relevant and more kinds of data into research that can ultimately improve patient outcomes. However, in this research paradigm, there must be greater transparency of benefits and risks, and permission processes that protect human rights and support truly informed consent.

Similarly, in “Assessing the Value of Patient-Generated Data to Comparative Effectiveness Research,” Lynn Howie and a research team from Duke cover how consumers’ data can better inform evidence-based clinical decisions. The authors discuss the growing role of sensors in health care, which generate data that can be married to traditional health claims to make research more patient-centered. National efforts have begun to use this approach such as the NIH Collaboratory, PCORnet, and CancerLinQ. Howie and the team say that aligning these national programs with patient communities like PatientsLikeMe, coupled with passively captured sensor data and genomic data, would create “streams of patient-centered data in a big data infrastructure.” The influx of quantitative data from patients that cover physical activity, nutritional intake, weight, and mood, turbocharge CER. The authors call for information to “traverse the boundaries of EHRs and health care systems.”

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Talking about using a “green button” for clinicians to use to aggregate data in EHRs at the point of care, Christopher A. Longhurst and colleagues from Stanford believe patient care could improve in real-time especially in the absence of published clinical evidence. The authors also argue for adding in data from pharmacy benefits, social media, and patients’ shopping habits which, mashed up with the patient’s EHR data and other sources, could support better patient care. Longhurst, and many of the experts published in this health care Big Data primer, ask whether HIPAA needs more than a tweak to cover a new era of privacy. Who knew in 1996, when HIPAA was codified, that cloud computing, smartphones, sensors, and online patient communities would become ubiquitous in the American health care landscape?

In the past month, FICO, the credit rating folks, published consumer survey results finding that most people in the U.S. would like to receive health care through their mobile phones. I wasn’t surprised by the finding – I’ve closely tracked the growing role of the internet and mobile platforms in health care for my living. What I’ve come to realize in just the last few years is the growing role of scoring moving from financial services into health care, and consumer life in general. Here is a field where FICO, pardon me, knows the score.

Add into this discussion a seminal essay by Ruth Faden and colleagues, “An ethics framework for a learning health care system: a departure from traditional research ethics and clinical ethics,” published in The Hastings Center Report in 2013, which sets forth the idea that patients are obliged to contribute to, participate in, and facilitate learning in health care. But do people, patients, consumers, and caregivers want to share their data for the benefit of both themselves and for others? There is (some) evidence that (some) people are indeed willing to share data “for good:” call it data altruism, a topic I’ve covered here in Health Populi.

There is indeed huge potential for good (to reduce costs based on sound clinical evidence and reducing waste, and drive the Triple Aim) in using Big Data in health care. Is there political and socio-cultural will to make this happen? Longhurst and his team ask at the conclusion of their essay. The technical issues of data analytics – the 3 V’s – are largely addressable in the current market environment. However, two other “Vs” — Value and Values — bubble up to the top of my reading this rich issue of Health Affairs. Specifically, (1) What Value is accrued to whom in the process of Big Data analytics in health care? and, (2) Whose Values will be taken into account in the data collection, algorithm-building, and interpretation of what comes out of the proliferating black boxes?

Here’s Looking at You: How Personal Health Information Is Being Tracked and Used, my next paper for the California HealthCare Foundation, will be published in mid-July 2014. The paper discusses the growth of consumer-generated data in health, and the opportunities and challenges that we should consider and discuss in this fast-changing field.

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast  This conversation with Lynn Hanessian, chief strategist at Edelman, rings truer in today's context than on the day we recorded it. We're

This conversation with Lynn Hanessian, chief strategist at Edelman, rings truer in today's context than on the day we recorded it. We're