![]()

![]()

![]()

Concerns about Death Panels and government restricting health services for people that have been key arguments used against the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) detractors and, even before the advent of the ACA, proposed health reforms under President Clinton.

Concerns about Death Panels and government restricting health services for people that have been key arguments used against the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) detractors and, even before the advent of the ACA, proposed health reforms under President Clinton.

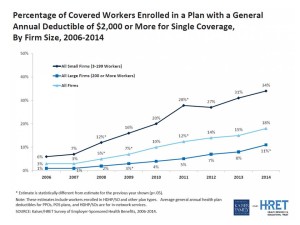

But it’s peoples’ self-rationing in the U.S. health system that’s causing true rationing — driven by high deductible health plans (HDHPs) that are fast-growing in the health insurance market, and by the high cost of specialty drugs and prescriptions.

There are plenty of data demonstrating the consumer health rationing trend being collected and reviewed by think tanks like RAND here, and by The Employee Benefits Research Institute (EBRI) here. A study published in 2013 found that when men’s deductibles rose, they sought health care less frequently in ERs and hospitals, but increased hospitalizations followed – implying that men may have avoided necessary health care after enrolling in a high-deductible health plan.

While the research into HDHPs is informative, it’s the patient stories covered in national media that bring full color to the issue of self-rationing due to growing first-dollar coverage among health consumers.

Unable to Meet the Deductible or the Doctor, published in the New York Times on October 17, 2014, talks about individuals with deductibles as high as $6,000 and families with deductibles up to $10,000, quote, “often hesitate to use their new insurance because of the high out-of-pocket costs.” That postponement of health services due to cost is a form of self-rationing, especially when an individual feels they need to seek treatment – whether for a sore throat (that might lead to bronchitis or pneumonia, unchecked) or a small lump detected in the shower during a breast self-exam.

Folks attracted to health insurance plans with lower monthly premiums, which have higher deductibles, may be least able to afford the treatment in real-time when they need it. Katherine Hempstead of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, who studies health insurance markets, is quoted in the New York Times article: “Unfortunately, the people who are attracted to the lower premiums tend to be the ones who are going to have the most trouble coming up with all the cost-sharing if in fact they want to use their health insurance.”

Health Populi’s’ Hot Points: Two factors enable people to become more empowered, informed health consumers: transparency of prices/costs and quality in advance of consuming a medical service or product, and the person’s willingness and activation to actually engage as a health care consumer.

To the first point on consumers’ ability to choose providers based on quality, note that HealthGrades, one of the most mature health care “report card” businesses, relaunches this week with a new-and-improved portal. USA Today covered this story on October 20 in New Doctors Site Rates for Experience, Quality. “The new version of the website Healthgrades.com uses about 500 million claims from federal and private sources and patient reviews to rate and rank doctors based on their experience, complication rates at the hospitals where they practice and patient satisfaction.”

To the second point on willingness and patient activation, health plan literacy today combines two aspects of life that the average human being doesn’t like to spend time thinking about often until it’s too late — money and health/care. Today’s emerging “consumer-directed” plan landscape, featuring high deductibles often coupled with health savings accounts, is a new-new thing for many people to deal with, while juggling home life, work life, care-giving, binge-watching of streaming media shows, and other must-do or want-to-do things that consume daily living in real-time, real-life.

Employing the art of value-based insurance design can help to nudge people to seek care when they need it – crucial for avoiding the unintended consequences, or negative financial side-effect, of an HDHP.

While the ACA has certainly expanded access for uninsured people to get covered, their understanding of the inverse relationship between a higher deductible vis-a-vis a lower premium, and one’s financial contractual obligation to cover first dollar payment for health services up to that deductible, isn’t translating at the point-of-purchase in the health insurance exchange marketplace. From the health consumer’s standpoint, especially for newbies with high deductible plans, it currently feels like health care in America is a pay-now-or-pay-later scenario where sticker shock is the new normal.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for