“It’s the prices, stupid,” wrote Uwe Reinhardt, Gerald F. Anderson and colleagues in the May 2003 issue of Health Affairs. Exactly twelve years later, three reports out in the first week of June 2015 illustrate that salient observation that is central to the U.S. healthcare macroeconomy.

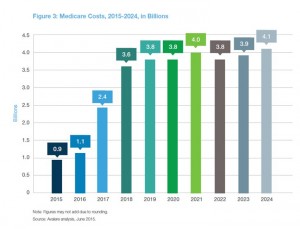

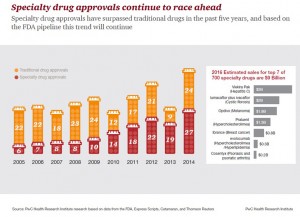

Avalere reports that spending on prescription drugs increased over 13% in 2014, with half of the growth attributable to new product launches over the past two years. Spending on pharmaceuticals has grown to 13% of overall health spending, and the growth of that spending between 2013-14 was the fastest since 2001. In light of this trend, Avalere quantified the impact of specialty drug costs on government programs Medicare, Medicaid, and the health insurance exchanges. Ten pipeline drugs designated as “breakthroughs” by the FDA were considered (note that these are 10 of about 5,400 meds in the total pipeline).

Avalere reports that spending on prescription drugs increased over 13% in 2014, with half of the growth attributable to new product launches over the past two years. Spending on pharmaceuticals has grown to 13% of overall health spending, and the growth of that spending between 2013-14 was the fastest since 2001. In light of this trend, Avalere quantified the impact of specialty drug costs on government programs Medicare, Medicaid, and the health insurance exchanges. Ten pipeline drugs designated as “breakthroughs” by the FDA were considered (note that these are 10 of about 5,400 meds in the total pipeline).

The 10 medications were estimated to cost government health plans nearly $50 billion over 10 years: $31 bn for Medicare, $16 bn for Medicaid, and $2 billion for insurance exchange plan subsidies. Clearly, it’s Medicare which has the greatest exposure to specialty drug cost sticker-shock. And this analysis is only for 10 new pipeline drugs. What the analysis does not take into account are costs averted by keeping patients out of hospital and other potential cost-savings averted due to using these novel products.

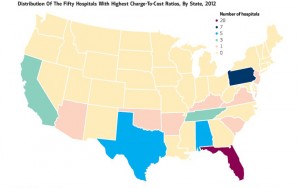

Gerald Anderson, co-author of the “Prices, Stupid” paper, returns this week in Health Affairs with colleague Go Bai authoring another seminal research piece called Extreme Markup: The Fifty US Hospitals With The Highest Charge-To-Cost Ratios. These hospitals’ price mark-ups are about ten times their Medicare-allowable costs versus national averages. The majority of these high mark-up institutions are for-profit, and 40% of them are located in Florida (THINK: Medicare and aging populations). One system, Hospital Corporation of America, owns one-half of the for-profit hospitals with greatest mark-ups. “Because it is difficult for patients to compare prices, market forces fail to constrain hospital charges,” Anderson and Bai conclude.

Gerald Anderson, co-author of the “Prices, Stupid” paper, returns this week in Health Affairs with colleague Go Bai authoring another seminal research piece called Extreme Markup: The Fifty US Hospitals With The Highest Charge-To-Cost Ratios. These hospitals’ price mark-ups are about ten times their Medicare-allowable costs versus national averages. The majority of these high mark-up institutions are for-profit, and 40% of them are located in Florida (THINK: Medicare and aging populations). One system, Hospital Corporation of America, owns one-half of the for-profit hospitals with greatest mark-ups. “Because it is difficult for patients to compare prices, market forces fail to constrain hospital charges,” Anderson and Bai conclude.

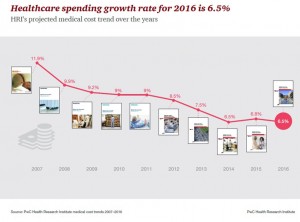

The third key health economic data point for the week comes from PwC’s Health Research Institute, whose annual medical cost trend report is out. Health care costs in the U.S. will growth 6.5% in 2015, as the chart shows, illustrated a flattening of health cost growth over the past 3 years. Compared with the high of nearly 12% in 2007, the year before the Great Recession hit the nation, 6.5% feels quite healthy. Compared with national consumer price inflation of a 0.2% decline in the 12 months to April 2015 and flat wage growth for Americans, 6.5% is a sticker-shock growth rate for the consumer’s household budget.

The third key health economic data point for the week comes from PwC’s Health Research Institute, whose annual medical cost trend report is out. Health care costs in the U.S. will growth 6.5% in 2015, as the chart shows, illustrated a flattening of health cost growth over the past 3 years. Compared with the high of nearly 12% in 2007, the year before the Great Recession hit the nation, 6.5% feels quite healthy. Compared with national consumer price inflation of a 0.2% decline in the 12 months to April 2015 and flat wage growth for Americans, 6.5% is a sticker-shock growth rate for the consumer’s household budget.

So PwC finds that cost-shifting is pushing consumers to become more mindful about healthcare choices: among people covered by employer-sponsored health plans:

- 28% skipped seeing a doctor

- 28% asked for a generic drug instead of a branded Rx

- 24% skipped taking the Rx or took less than prescribed

- 20% skipped seeing a specialist

- 18% skipped follow-up care, like physical therapy recommended by their physician

- 16% skipped or delayed a procedure or treatment….

…due to the cost of care. Remember: these self-rationing actions were taken by people insured through employer-sponsored plans — not uninsured people.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: U.S. health consumers are paying a growing proportion of health care costs, driving more consumer behavior in many ways. For consumer goods, moving from high-priced aged sirloin steak to ground beef could be fiscally rational; buying generic store brands that are private labelled in the frozen food aisle can make a lot of sense. Self-rationing care, as found by PwC among insured people? Not so rational in the long-run, overall. There may be instances of overtreatment that are averted, certainly; but delaying necessary procedures, avoiding specialists for a potentially serious diagnosis, and skipping or slowing medications against prescribed recommendations? These short-term fiscal health decisions can result in longer-term physical health exacerbations.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: U.S. health consumers are paying a growing proportion of health care costs, driving more consumer behavior in many ways. For consumer goods, moving from high-priced aged sirloin steak to ground beef could be fiscally rational; buying generic store brands that are private labelled in the frozen food aisle can make a lot of sense. Self-rationing care, as found by PwC among insured people? Not so rational in the long-run, overall. There may be instances of overtreatment that are averted, certainly; but delaying necessary procedures, avoiding specialists for a potentially serious diagnosis, and skipping or slowing medications against prescribed recommendations? These short-term fiscal health decisions can result in longer-term physical health exacerbations.

One area to watch is specialty drugs, which are increasingly in the radar of health care payors — both institutional payors like employers and plan sponsors (Medicare, unions) and, increasingly, consumers themselves. My colleague Brian Klepper asked in Employee Benefit News on May 27, 2015, “Will specialty drug pricing be the straw?” That would be the “straw” that breaks the immovable camel’s back of payors not lashing back at health care prices. Now that payors include consumers, who cover 43% of prescription drug costs according to Kalorama Information’s latest look into out-of-pocket costs, Brian — whose has been working closely with employers around the U.S. over the past decade — has the forecast just right.

Avalere’s analysis did not account for the full value and patient outcomes of using the ten specialty drugs in its study. Value in the new value-based payment era in health/care is the opportunity for health industry stakeholders to stake a claim in overall health, and not just speak in terms of health costs. As Dr. Mark Fendrick who directs the University of Michigan Center for Value-Based Insurance Design has recommended, “We need to change the conversation from how much things cost to how much health they produce.”

That, and arming health consumer-payers with tools and information that they can use to make rational judgments about where and when to seek care in the high-deductible health plan world.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for