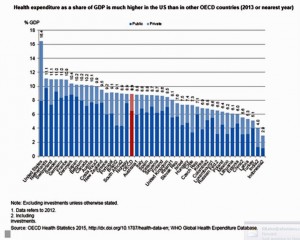

People in the U.S. have lower life expectancy, a growing alcohol drinking problem, and relatively high hospital inpatient rates for chronic conditions compared with other OECD countries. And, the U.S. spends more on health care as a percent of GDP than any other country in the world. This isn’t new-news, but it confirms that U.S. health citizens aren’t getting a decent ROI on health spending compared with health citizens around the developed world.

People in the U.S. have lower life expectancy, a growing alcohol drinking problem, and relatively high hospital inpatient rates for chronic conditions compared with other OECD countries. And, the U.S. spends more on health care as a percent of GDP than any other country in the world. This isn’t new-news, but it confirms that U.S. health citizens aren’t getting a decent ROI on health spending compared with health citizens around the developed world.

In the OECD’s latest global look at member countries’ health care performance, Health at a Glance 2015, released today, the U.S. comes out not-so-healthy in the context of other wealthy countries. The OECD suggests Americans’ health behaviors and the nation’s fragmented health system contribute to diminished life expectancy. The U.S. has the highest obesity rate among OECD peers. And alcohol consumption is up, which we noted in yesterday’s Health Populi as a contributor to middle-age mens’ growing challenge with cirrhosis and liver disease.

The U.S. scores highly on saving lives: once a patient is ill and admitted to hospital, American acute healthcare is top-notch on a global basis.

Overall, chronic disease is growing around the world, and no nation has universally cracked prevention and health behavior change.

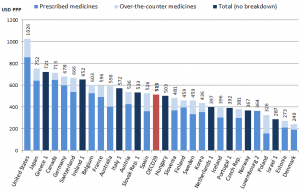

The fastest-growing component of health care spending in the U.S. is specialty drugs, discussed here in Health Populi.

The fastest-growing component of health care spending in the U.S. is specialty drugs, discussed here in Health Populi.

The OECD report goes into detail on pharmaceutical spending across the member nations, citing that the U.S. spends more on prescription drugs than any other nation (see the second chart). Pharma spending has slowed in most of the OECD; in the U.S., the percent of drug spend in the total health care bill is reaching 20%, OECD calculates. The emergence of specialty drugs in health spending will comprise at least one-half of pharma spending within five years, OECD forecasts.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: There is a growing gap between health status of Americans and the health of peer health citizens in other wealthy countries. U.S. men live 4.3 years less than those in Switzerland (a 1.3 day loss since 1970); and U.S. women live 5.4 years less than our peer females in Japan.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: There is a growing gap between health status of Americans and the health of peer health citizens in other wealthy countries. U.S. men live 4.3 years less than those in Switzerland (a 1.3 day loss since 1970); and U.S. women live 5.4 years less than our peer females in Japan.

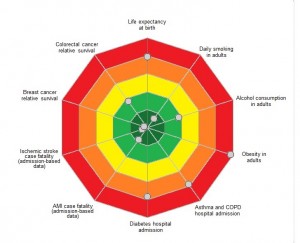

The target chart illustrates selected U.S. health metrics compared with OECD peer nations. The closer the dots to the center of the bullseye, the better the country is doing relative to others. The outermost dots — which are the areas of poor healthcare performance — including (starting at “midnight” and moving clockwise) life expectancy at birth, obesity in adults, asthma and COPD hospital admissions, and diabetes hospital admissions.

Where the U.S. does well is smoking reduction, AMI case fatality (heart attacks admitted to hospital), ischemic stroke case fatality (admitted to hospital), and breast cancer survival.

This means that the U.S. does very well with people who are sick — the expensive components of health spending such as inpatient care and high-tech procedures — versus prevention downstream, and a well-funded primary care infrastructure that extends to all health citizens — enjoyed by those who live in other OECD countries. I’ve covered this issue of the primacy of primary care extensively here on Health Populi.

OECD points to the fragmented health care delivery structures in the U.S. contributing to poor overall mortality, and higher health care costs. The sooner the nation moves toward value-based health care and an emphasis on primary care and self-health care, the sooner that upwardly bending cost curve can be moderated. But keep an eye on specialty drug costs in that value-based world: proven end-points and health outcomes studies, and patient inputs into quality of life and side effects, will be important inputs into which specialty drugs get paid-for, and which don’t in that value-based world. Remember: Medicare plans to migrate 50% of payments into that new reimbursement regime in 2018.

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a