“It depends” is the hedge-phrase that characterizes how Americans see disclosing personal information versus keeping private information private, according to the consumer survey report, Privacy and Information Sharing, published by the Pew Research Center (PRC) in January 2016.

“It depends” is the hedge-phrase that characterizes how Americans see disclosing personal information versus keeping private information private, according to the consumer survey report, Privacy and Information Sharing, published by the Pew Research Center (PRC) in January 2016.

U.S. adults see a privacy trade-off, living in the convenience-context of 21st century digital economy in exchange for some form of value. The “it depends” is a factor of what kind of data is geing collected, especially by third parties, how long that data area retained, for what use — vis-à-vis what a person is trading in return which could be a hard dollar value, convenience, knowledge, or support of some kind.

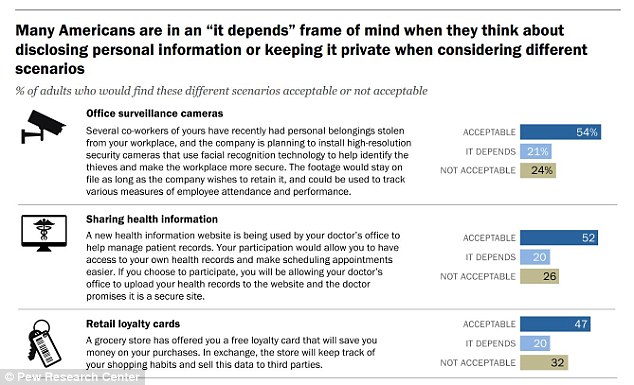

PRC developed six scenarios describing consumers and the “it depends” frame of mind, shown in the first chart. The six scenarios are:

PRC developed six scenarios describing consumers and the “it depends” frame of mind, shown in the first chart. The six scenarios are:

- Office surveillance cameras

- Sharing health information

- Retail loyalty cards

- Auto insurance

- Free social media, and

- Smart thermostat.

We’ll focus here in Health Populi on the scenario of sharing health information, although all have some adjacency to health, broadly defined.

“Sharing health information” was seen as acceptable by 52% of U.S. adults, with 20% saying, “it depends.” Fully one-fourth of Americans, 26%, said sharing health information is “unacceptable” under any conditions.

The scenario is defined as “a new health information website [is] being used by your doctor’s office to help manage patient records. Your participation would allow you to have access to your own health records and make scheduling appointments easier. If you choose to participate, you will be allowing your doctor’s office to upload your health records to the website and the doctor promises it is a secure site.”

This scenario is akin to an online patient portal, which most physicians and hospitals have been implementing as part of achieving their HITECH incentive for adopting electronic health records and “meaningfully using” them. Thus, from the health industry’s viewpoint, this scenario is fairly normal and mainstream.

However, from the consumer’s view, only one-half buy into the patient portal concept. For 1 in 5, “it depends.” And for 1 in 4 people, “no way” would I participate in a patient portal, even with easy scheduling online — a convenience that a majority of consumers are keen on in several previous surveys.

PRC points out that their previous surveys have found Americans sensitive about personal health information, concerned about how PHI could be re-used in ways that could jeopardize access to insurance, credit (say, for a mortgage), or a job application.

Older people are more open to sharing health data than younger people, Pew found, and people with higher education are, as well.

Overall, the “it depends” and privacy-absolutists are concerned about the following issues, which Pew gleaned through the survey:

- The initial bargain might be fine but the follow-up by companies that collect the data can be annoying and unwanted

- Scammers and hackers are a constant threat

- Location data seems especially precious in the age of the smartphone

- Profiling sometimes seems creepy (substitute “Big Brother” or “stalking” for “creepy”)

- People are not happy when data are collected for one purpose but are used for other, often more invasive purposes

The flip-side of these concerns are the potential benefits of personal data sharing, which include:

- Free, a good price for, say, social media, email addresses, online storage, and other digital goodies

- Sharing can help “lubricate” commercial and social interactions

- Certain realms are not inherently private and different rules about surveillance and sharing might apply.

The Pew Research Center surveyed 461 U.S. adults ages 18 or older in January and February 2015, which was a sub-sample of a 607 person panel culled by GfK in 2014. In addition, Pew conducted nine focus groups in January 2015 for additional qualitative insights.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The February edition of Scientific American includes an article in the Health section titled, “How Data Brokers Make Money Off Your Medical Records.” This essay echoes what I wrote in my paper, Here’s Looking At You: How Personal Health Information is Being Tracked and Used, published by the California HealthCare Foundation in February 2015.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The February edition of Scientific American includes an article in the Health section titled, “How Data Brokers Make Money Off Your Medical Records.” This essay echoes what I wrote in my paper, Here’s Looking At You: How Personal Health Information is Being Tracked and Used, published by the California HealthCare Foundation in February 2015.

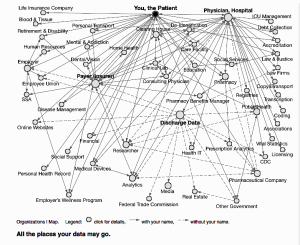

See the third graphic which comes from the Harvard Privacy Project: the spiderweb-type lines show data flows of personal health information in the U.S. that is not covered by HIPAA. Most consumers are unaware what HIPAA covers, and knowing about these data flows would no doubt surprise many people.

There are many levels of health literacy required to become a fully-functioning, effective health care consumer in America in 2016. One of these onion-layers-of-literacy is becoming health data literate in terms of how to both ask for one’s personal health information (from physicians, hospital administrators, pharmacies, mental health professionals, and other providers), and how to be a good data steward and protector for one’s own PHI.

Share the diagram with your friends and family, as well as a link to the Scientific American column. While the Pew survey demonstrates that people are willing to make a deal for sharing their health data, just how and with whom to cut those deals continues to lack transparency and platforms for doing so. People must advocate for themselves, and for each other, in this Brave New World of Big Health Data.

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a