Patient engagement is the new imperative in health care, writes Editor-in-chief Alan Weil in his introduction to the April 2016 issue of Health Affairs.

Patient engagement is the new imperative in health care, writes Editor-in-chief Alan Weil in his introduction to the April 2016 issue of Health Affairs.

It is appropriate and right that Judith Hibbard of the University of Oregon served as the theme adviser for the issue: she’s the innovator of the Patient Activation Measure and has frequently published her research in Health Affairs. Her own bottom-line: that the higher the patient activation, the less health care costs the health plan. (See a recent post on her research here on Health Populi).

This issue of Health Affairs is a comprehensive primer on the many aspects of evolving consumerism in health care.

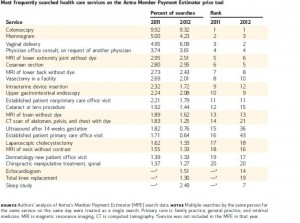

One sign of growing healthcare consumerism is health care “shopping,” with more patients-cum-consumers seeking transparency for price, quality, and availability of healthcare goods and services. Anna Sinaiko and Meredith Rosenthal, both of Harvard’s Chan School of Public Health, examine whose health-price shopping and how they’re doing it. Using data from Aetna’s Member Payment Estimator, the researchers found that, in 2012, the most commonly searched services were colonoscopy, vaginal delivery, mammogram, physician office consult, and C-section; together, these five services comprised 26% of all searches consumers conducted. Note that two of these services are preventive, and two deal with pregnancy. Among patients receiving services, searchers were more likely to be younger and healthier and to have higher annual deductible spending; the researcher regression analysis bore out the hypothesis that patients who incur higher annual deductibles were more likely to use the Member Payment Estimator. More were women, as well (note the influence of childbirth as two of the top-five most-searched services).

A second aspect of consumerism is understanding out-of-pocket costs. The theory of consumers’ “skin in the game” is to nudge people toward higher-value and -quality services. Peter Ubel and colleagues studied the role of physician-patient communication and the opportunity to help reduce patients’ out-of-pocket (OOP) spending. Ideally, the authors assert, “When patients are burdened by the expense of interventions, physicians should consider whether there are less expensive alternatives.” However, Ubel et. al. identified several missed opportunity scenarios in this relationship, including:

- Physicians’ failure to recognize potential financial concerns

- Distractions from patients’ financial concerns via frustration with the system

- Dismissal of patients’ financial concerns

- Hasty acceptance of patients’ dismissal of their own financial concerns

- Assuming “coverage” means full coverage

- Assuming generic medications are affordable

- Assuming co-payment assistance programs and coupons would resolve financial concerns

- Making short-term fixes without dealing with the patients’ longer-term financial challenges

- Failure to consider less-expensive alternatives.

Patient-Clinician conversations are discussed in a Viewpoint piece from Ian Hargraves and colleagues from the Mayo Clinic. The researchers distinguish between a health provider pushing “information” to a patient versus having a conversation with that patient. Conversations would be a basis for effective shared decision-making between doctors and patients, the authors explain, based on ten years’ worth of experience at Mayo Clinic. “We’ve learned that providing patients with information or evidence alone isn’t sufficient to support patients who are making a decision,” the Viewpoint states. The traditional assumption is that serving up technical medical information in “patient-friendly formats” would give said patients sufficient resources for their personal clinical decision-making. Not so: the real challenge is using evidence to discover what’s best for a particular patient in the context of their own values and preferences. “The medium in which this happens is patient-clinician conversation,” Hargraves and team have learned. While it’s necessary for clinicians to assess and communicate benefits and risks to patients, it is not sufficient. What matters is what matters to each individual patient.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Ubel and colleagues wrote about the lack of out-of-pocket expense conversations between doctors and patients as part of a larger “general failure of the U.S. health care system. Physicians in the U.S. have difficulty factoring financial concerns into health care decisions in part because out-of-pocket spending is often difficult to determine and health care prices are often opaque.” That gets to the importance of price transparency, which Sinaiko and Rosenthal discussed in their contribution discussing health plan members’ searching the Aetna Estimator tool. But healthcare is a team sport, and shared decision-making, informed by the Mayo Clinic experience, is a healthcare Holy Grail.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Ubel and colleagues wrote about the lack of out-of-pocket expense conversations between doctors and patients as part of a larger “general failure of the U.S. health care system. Physicians in the U.S. have difficulty factoring financial concerns into health care decisions in part because out-of-pocket spending is often difficult to determine and health care prices are often opaque.” That gets to the importance of price transparency, which Sinaiko and Rosenthal discussed in their contribution discussing health plan members’ searching the Aetna Estimator tool. But healthcare is a team sport, and shared decision-making, informed by the Mayo Clinic experience, is a healthcare Holy Grail.

As the shopping ladies in the cartoon admit, “most of my consumerism is self-taught.” It is indeed early days for patients to embrace full-on consumerism in health care, notwithstanding many years of health plans and employers risk-shifting growing financial burdens to employees and plan members. Their learning curve will be much smoother if the on-ramp supports shared decision-making and health literacy in its many forms: health financial literacy, health plan literacy, and digital literacy. Clinicians will learn as much from patients as patients will from their trusted providers.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for