The nation’s largest retail pharmacy chain signed a deal to combine with one of the top three health insurance companies. The deal is valued at $69 billion.

I wrote about this inflection point for U.S. healthcare four weeks ago here in Health Populi.

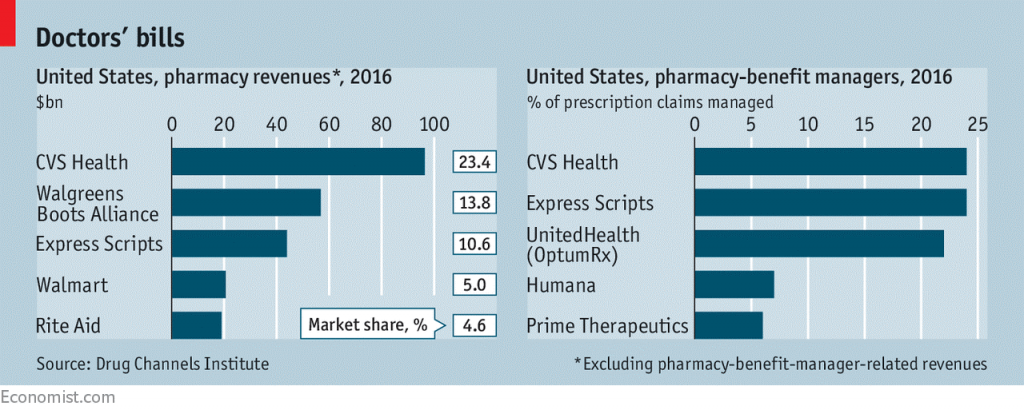

CVS is both the biggest pharmacy and pharmacy benefit manager in the U.S., as the first chart shows. In my previous post, I talked about the value of vertical integration bringing together the building blocks of retail pharmacy and pharmacist care, retail clinics, the PBM (Caremark), along with Aetna’s health plan member base and business.

As Amazon and other entrants bring their innovative approaches and technologies into American healthcare, consumers are expecting more streamlining, convenience, and lower prices. The legacy healthcare system — hospitals, insurance companies, and pharma — haven’t delivered on that expectation.

Vertical integration can help because patient hand-offs between different sites of care can be more continuous, information can be interoperable (that is, flow more effectively through and between health data systems — note that CVS uses Epic electronic medical records systems), and bolster better quality at a lower cost. The Economist noted that integrated care has been a secret in the sauce of the healthcare-integrated systems Intermountain, Kaiser Permanente, and the Mayo Clinic.

There will be regulatory scrutiny at the Federal Trade Commission to undergo. But this deal is vertical in nature, that is complementary health care business. This is not the kind of horizontal merger that would have consolidated Aetna and Humana — in a deal that got rejected by the FTC due to antitrust monopoly concerns.

Anticipating this deal would come to fruition, Reuters reported that CVS would look to expand brick-and-mortar healthcare services in the form of more ambulatory clinics. Underlying this strategy would be to leverage the company’s 9,700 storefronts and promote prevention, medication therapy management, and appropriately triaged clinic care to prevent unnecessary use of expensive emergency rooms.

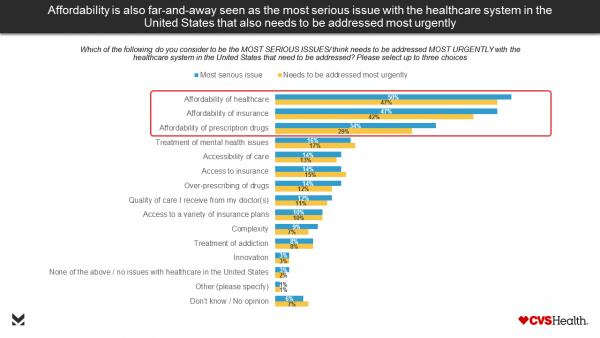

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Last week, CVS published the results of a consumer survey, conducted in October 2017, about the state of U.S. healthcare. Most Americans say thinking about the nation’s healthcare system makes sad, pessimistic, and angry — not proud or optimistic. By far, the most serious issues facing American healthcare consumers are the lack of (1) affordable care, (2) affordable insurance, and (3) affordable drugs, shown in the bar chart.

Over the past few weeks, there have been several signs that the prescription drug industry has several eagle eyes focused on lowering the price of medicines. I’ll point to three key moments: first, during the hearing of Alex Azar II, President Trump’s appointee to lead the Department of Health and Human Services, testified to the Congressional committee that he would be keen to enact tactics that lower drug prices, such as allowing Medicare to negotiate directly with drug companies. Note that Azar was once President of Eli Lilly, among the world’s largest pharma companies and marketer of products that treat diabetes, among other conditions. During the hearing, Senator Patty Murray (D-WA) challenged Azar, “As a pharmaceutical executive, you raised drug prices year after year. Eli Lilly is currently under investigation for working, under your tenure, with other drug companies to needlessly raise the price of insulin.”

Second, the National Academy of Science published a well-researched report supporting government prescription drug price negotiation. The Academy convened a team with experience and gravitas to inform this report. In parallel with the publication of this report were also dissenting opinions from two participants who came out of the pharma industry: Michael Orsenblatt, formerly President and Chief Medical Officer at Merck, and Henri Termeer, former CEO of Genzyme. “Allowing all government health plans to negotiate as a single block would establish a near monopoly,” the document asserted.

Third, pharmacists in the state of Michigan launched a campaign to educate Michiganders about the high price of medicines in the state and potential solutions to the challenge.

CVS/pharmacy rebranded itself as CVS/health three years ago when the company quit the tobacco-selling business and doubled-down on health-focused investments. The Economist (whose art is shown in the third image), asked on November 4, 2017 whether this merged organization could deliver “the right dose” for U.S. healthcare. Clearly, CVS needs to grow behind the retail pharmacy and come out in front of the counter as part of its growing health/care focus as the company’s sale of prescription drugs has recently slowed and prospects for pricing and disruption via Amazon loom close.

CVS/pharmacy rebranded itself as CVS/health three years ago when the company quit the tobacco-selling business and doubled-down on health-focused investments. The Economist (whose art is shown in the third image), asked on November 4, 2017 whether this merged organization could deliver “the right dose” for U.S. healthcare. Clearly, CVS needs to grow behind the retail pharmacy and come out in front of the counter as part of its growing health/care focus as the company’s sale of prescription drugs has recently slowed and prospects for pricing and disruption via Amazon loom close.

Aetna’s business, too, needs to scale in new ways, as the health insurance business seeks certainty, business models, and scale economies.

Considering the CVS + Aetna combination through health consumers’ eyes, vertical integration can be a good thing for patients and caregivers if the company can streamline and artfully design delightful experiences while serving up value-based care in terms of both cost-value and patients’ own values with greater skin-in-the-healthcare-payment-game.

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a