New research points out that real people live real lives, and our assumptions about social determinants of health (SDOH) may need to be better informed by those real lives. I read three reports in the past week sobering up my bullish #SDOH ethos dealing with food deserts, transportation, and health service access — three key social determinants of health.

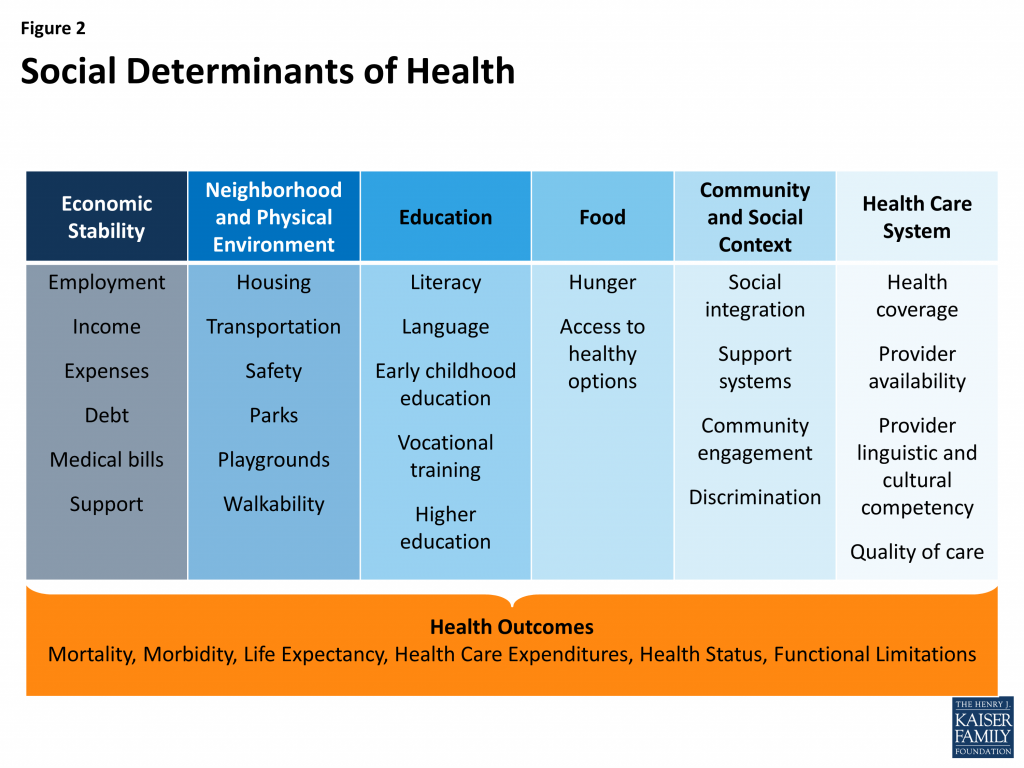

To remind you about the social determinants, here’s a graphic from Kaiser Family Foundation that summarizes the key pillars of SDOH.

To remind you about the social determinants, here’s a graphic from Kaiser Family Foundation that summarizes the key pillars of SDOH.

Assumption 1: Food deserts in and of themselves diminish peoples’ healthy nutrition lifestyles. Low-income households who are exposed to the same food-buying opportunities as higher-income households reduce nutritional inequality by only 9%, based on research from the NBER. Geography of Poverty and Nutrition: Food Deserts and Food Choices Across the United States found that nutritional disparities have more to do with peoples’ demand for healthier foods than the nature of the supermarket supply in their neighborhoods. NBER concluded that education, nutritional knowledge, and regional food preferences are strong influences in consumers’ food selection on the demand side, versus a supply side of greener, fresher or more nutritious choices. The Study also found that consumers who move to areas where other people tend to eat more healthy foods do not change their own eating patterns.

Assumption 2: Providing transportation to/from health care services will bolster patients’ appointment-making. About 3.6 million U.S. adults miss medical appointments each year due to transportation challenges, many of whom earn lower incomes. A study in JAMA Internal Medicine learned that providing shared transportation through, for example, Lyft or Uber, does not in itself increase appointment show-ups. Patients’ missed-appointment rates were roughly equal between those offered a ride service and those who were not: 36.5% versus 36.7%.

Assumption 2: Providing transportation to/from health care services will bolster patients’ appointment-making. About 3.6 million U.S. adults miss medical appointments each year due to transportation challenges, many of whom earn lower incomes. A study in JAMA Internal Medicine learned that providing shared transportation through, for example, Lyft or Uber, does not in itself increase appointment show-ups. Patients’ missed-appointment rates were roughly equal between those offered a ride service and those who were not: 36.5% versus 36.7%.

Assumption 3: Peoples’ access to health care services boosts outcomes. Just because a patient has access to health services doesn’t mean their outcomes will improve. In the Effect of High-Deductible Insurance on High-Acuity Outcomes in Diabetes, researchers found that overall, patients’ use of health services declined and led to 3.8% lower costs. However, among patients that lived in low-income neighborhoods, “large concerning” high-acuity emergency department visits and inpatient hospital days significantly increased. The study was published in the January 2018 issue of Diabetes Care, the journal of the American Diabetes Association.

In each of these studies, making the typical SDOH assumptions providing a single solution didn’t yield the intended outcome.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: These studies point to our ongoing need to be ruthlessly focused on user-centered design — in this case, patient- and consumer-centered design, based on and respecting peoples’ values and life-flows.

Take the example of patients with diabetes and high-deductible health plans. New research from Roche, partnering with Alexa Von Tobel of LearnVest, a personal financial planning firm, found that Americans with diabetes are more concerned about their financial future than people without the condition. To cover the costs of their diabetes care, nearly 1 in 2 people with diabetes accrued credit card debt (22%), borrowed money from family or friends (21%), and/or withdrew money from a retirement or savings account (19%).

In this case, people managing diabetes are not only at-risk for managing the many daily work-flow components of their condition, such as mindful nutrition and blood glucose testing: they’re also at financial-risk with its own stresses and household challenges.

The authors of the transportation study sum up the SDOH challenge as follows: “We need to be thoughtful about how we design and test new programs that address social barriers to health care….While we want hospitals and health systems to address patients’ social challenges that impact health — we need to rigorously evaluate new programs to make them successful. In this case, addressing transportation alongside other barriers could make a difference or doing a better job identifying who needs the services.” In the case of providing a Lyft or Uber to drive someone to an appointment scheduled at 3 pm, the healthcare provide might not realize the patient works an hourly job until 5 pm weekdays, so cannot get to an appointment during typical “office hours.”

Those other barriers the transport research calls out can include financial — a top consumer health issue with which regular Health Populi readers will be well aware — along with cultural preferences, job and work commitments (limiting time to seek care inside of “regular” operating hours), and institutional barriers such as racial and ethnic factors that prevent some people trusting healthcare institutions.

Those other barriers the transport research calls out can include financial — a top consumer health issue with which regular Health Populi readers will be well aware — along with cultural preferences, job and work commitments (limiting time to seek care inside of “regular” operating hours), and institutional barriers such as racial and ethnic factors that prevent some people trusting healthcare institutions.

When doing the important work with social determinants, let’s make sure we address and embrace the wholeness and richness of people’s 24×7 lives. To that end, here’s a helpful report to help us on our journey toward whole-person care.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for