“It’s not about shiny new technologies but about designing relationships to truly impact the patient at the center of the disconnected ecosystem,” asserted Amy Cueva, Founder and CXO of the design consultancy Mad*Pow. That patient is a consumer, a caregiver; it’s you and me, Cueva explained.

To reconnect the fragmented pieces of healthcare delivery, Cueva said, mantra-style, “collaboration is the new innovation.” And collaboration with patients, caregivers — the people for whom that healthcare is aimed — is the optimal workflow for effectively, enchantingly designing healthcare.

In a talk she delivered at the Innovation Summit in a preconference meet-up at the annual 2018 HIMSS conference, Cueva took us back to design’s roots through the eyes of John Norman, author of the book The Design of Everyday Things.

Norman tells us to look beyond the aesthetic beauty of everyday things to how intuitive things are to use, Cueva suggested. “Design isn’t about a single object but how many objects can work together as system to impact peoples’ lives.”

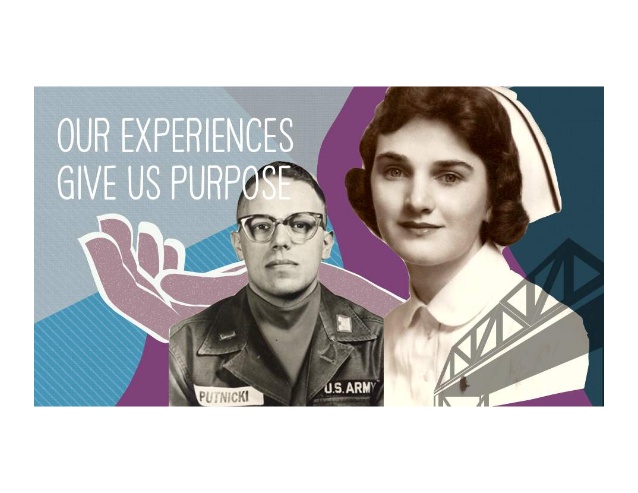

In addition to seeking system-ness in design, there’s a deeper human instinct that should inform design: purpose. “Our experiences give us purpose. Empathy and design are hardwired into our DNA,” Cueva has learned. Connecting the dots between DNA and human-centered design, Cueva shared a very personal perspective with us about her parents, whose pictures are in this image.

Cueva came to intimately appreciate what person-centered design means for healthcare.

Nine months ago, this because “crystal clear” to her she said, via a call from Dad – the kind of call none of us wants to receive from a loved one. Cueva’s mother had been diagnosed with glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer. Dad didn’t know how much longer Mom would live.

”Mom’s situation taught me about empathy. Only when we’ve really experienced a system on the first day first-hand can we begin to understand how far we need to go to change the situation,” Cueva shared. “When you experience a doctor who is desensitized and jaded versus a doctor getting to know the whole person,” you come to learn, as a caregiver of a loved one, how abusive and difficult the U.S. healthcare system can be on both the patient and her family.

Here’s what real life looks like. A patient might want a Dove ice cream bar in the moment of the bad news of a tough diagnosis. Two sisters argue about therapy options that could save mom’s life, but have toxic side effects. You comb the Internet for research on a disease you can barely pronounce to find information on how to save the life of your loved one, while coming to terms that you might lose her. You get lost in the system.

So many people have been there, Cueva empathized. “We are trying to humanize the health system with greater sense of empathy, purpose and inclusion for people dependent on us to create solutions that will bring positive benefit to their lives.”

We must think about moving beyond human-centered design to purpose-driven design, aligning the mission of healthcare organizations with their greater sense of purpose. Doing so can give the organization a helpful filter for decision making, inform rational investment choices, address corporate social responsibility, and eventually develop services that patients and caregivers might come to love.

Ultimately, empathic design must address a person’s sense of:

- Autonomy, responding to our human need to have control over ourselves and make meaningful choices

- Competence, reinforcing our need to learn, grow, and succeed; and,

- Relatedness, where we feel like we’re part of something bigger than ourselves.

“We are the design,” Cueva concluded. That is we the people, the person, the patient.

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a