The U.S. spent nearly twice as much as other wealthy countries on healthcare, mostly due to higher prices for both labor and products (especially prescription drugs). And, America spends more on administrative costs compared to other high-income countries. What do U.S. taxpayers get in return for that spending?

Lower life spans, higher maternal and infant mortality, and the highest level of obesity and overweight among our OECD peer nations.

These sobering statistics were published in Health Care Spending in the United States and Other High-Income Countries this week in JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The study analyzes healthcare spending and outcomes across eleven countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the world’s wealthiest nations.

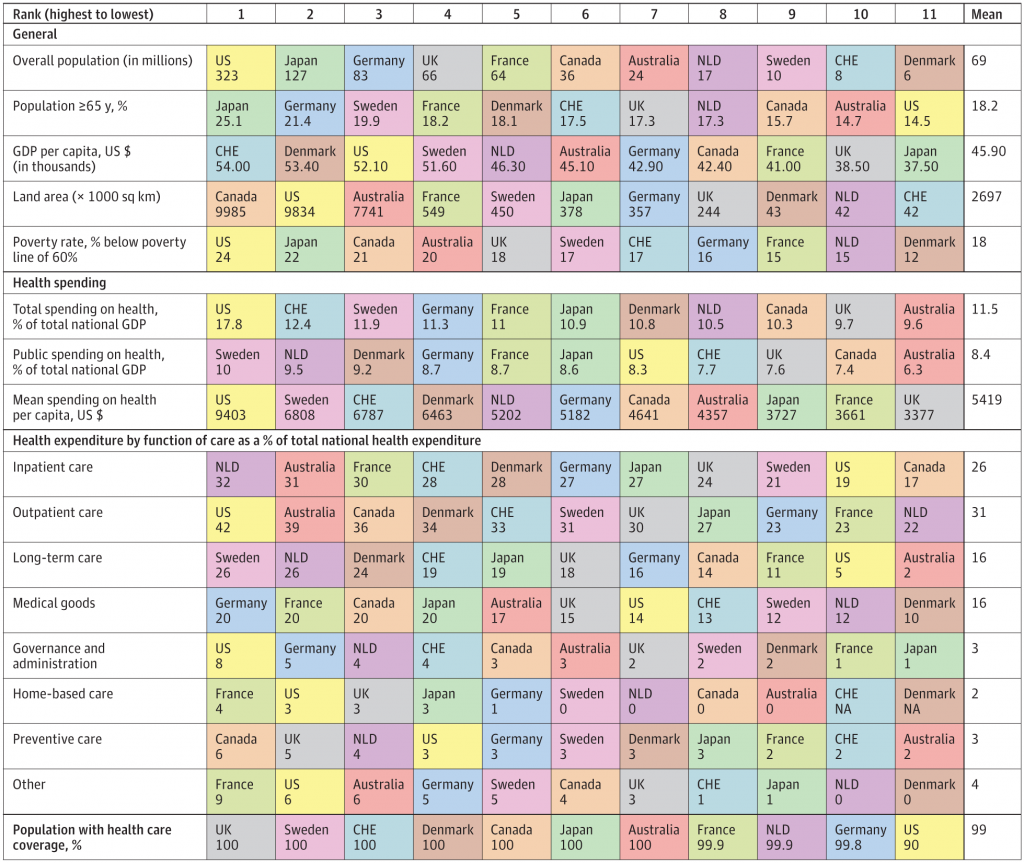

The first chart shows the data on “inputs:” spending on healthcare overall, and split into categories of inpatient care, outpatient care, long-term care, and other categories. U.S. data are shown in yellow.

Some important line items stand out. Note the last line of that matrix, population with health care coverage: the U.S. ranks lowest on that, at 90%. [It’s important to realize that this statistic is based on data from 2016 at a historic high, when the Affordable Care Act was in full implementation].

“Relative to comparison countries, US performance varied on quality and access measures. Of the other countries examined, the United States was the only one in which a sizeable minority (approximately 10%) of individuals lacked coverage for basic health care services,” the report calls out.

Also see the poverty rate, percent of the population below poverty, is highest in the U.S. across the OECD nation-peers.

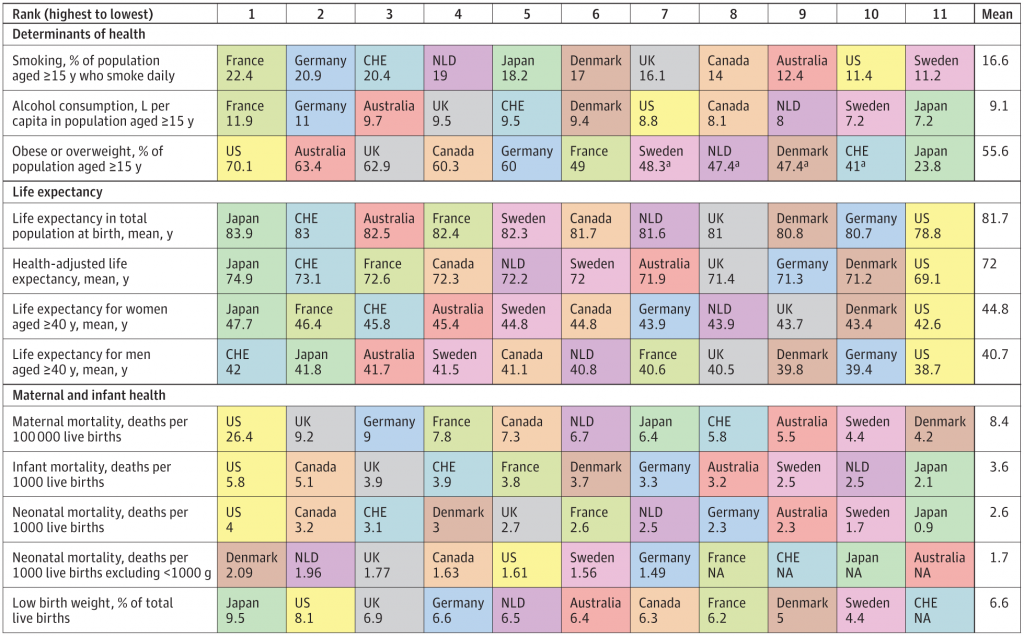

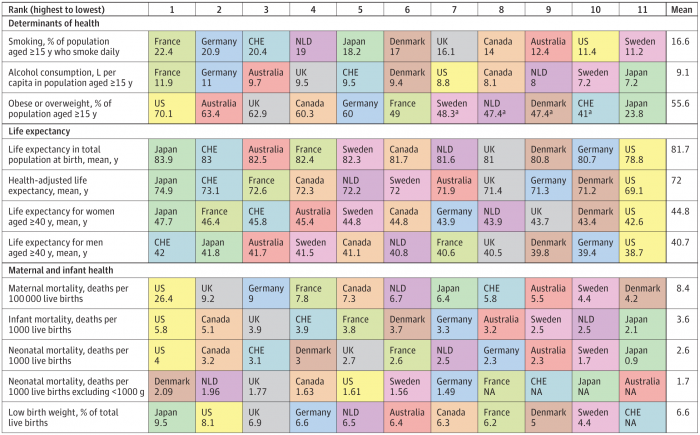

Now turn your eyes to the second chart, which  is titled “Population Health” in the report. This matrix ranks the wealthy nations on determinants of health, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and obesity; life expectancy; and maternal and infant health.

is titled “Population Health” in the report. This matrix ranks the wealthy nations on determinants of health, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and obesity; life expectancy; and maternal and infant health.

Some of the key findings on America’s higher costs/poorer outcomes are that:

- The U.S. spends more than double the average costs on administration at 8% of GDP compared with 3% of GDP across the OECD nations.

The U.S. had the highest pharmaceutical spending per capita of $1,443 versus $749 for the other nations, roughly double.

Access and quality of care in the U.S. varied, with that 10% of health citizens lacking coverage for basic health care. On quality, the U.S. had a higher avoidable hospitalization rate for diabetes and asthma compared with other countries.

Finally, people in the U.S. rated the lowest satisfaction with their health system, where only 19% said the health system works well.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: One of the first books I read as a young economics student, before diving into the microeconomics of healthcare, was Victor Fuchs’ book, Who Shall Live? Health, Economics, and Social Choice. The tagline of the book explains the plot: how we allocate resources is a conscious choice that impacts individual and collective health.

That the U.S. spends roughly the inverse on social care versus health care compared with peer wealthy nations is a key reason for America’s poor outcomes on so many metrics: life expectancy, maternal mortality, infant mortality, and obesity which drives greater utilization of health care services and prescription drugs.

It’s all about prices, this study concludes, where the cost of our inputs — hospital beds and labor rates, and administrative cost/waste — drive up spending as well as ration peoples’ access to those services when they need them…often causing greater spending downstream when a condition can worsen or get more complicated.

The study points to salaries of generalist and specialty physicians in the U.S. being “markedly higher” than in other countries, with specialists paid twice as much in the U.S. as in the U.K. and Germany. Overall, it’s a greater than $200,000 difference between U.S. and other nations’ doctors — who may be underpaid overseas, the study points out.

The report hints at the different (read: lesser) emphasis on primary care in the U.S. compared with most other OECD countries which have stronger and more accessible primary care backbones than America’s. While data in this study didn’t connect social care spending to lower performance on social determinants, the primary care on-ramp may be where America’s health care rubber should hit the road with greater spending there — on accessible primary care in the community, in retail settings, in schools, in pharmacies, and at home by bolstering self-care. Move care to the home via telehealth, enabled through net-neutral broadband, can help if we treat connectivity as a social determinant/public utility the way public health looks at clean air and clean water.

Consumers who use more primary care can lower healthcare costs, as this blog in Health Affairs pointed out this week. This phenomenon has been known for many years through the seminal work of Dr. Barbara Starfield.

I return to Fuchs as I often do, asking the question: “Who Shall Live” in America? If healthcare in the U.S. continues on its unaffordable pathway, then it will be those who can afford care and services who will be more likely to live.

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider

I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider  Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for