In the US, when it comes to life and death, it’s good to live in Hawaii, Utah, Minnesota, North Dakota, and Iowa — the top five states with the greatest life expectancy and healthy life expectancy at birth in 2016.

For health and longevity, sorry to see the lowest five ranked states are Washington DC which ranks last, along with Mississippi, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Alabama.

This sober geography-is-health-destiny update was published this week in JAMA, The State of US Health, 1990-2016: Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Among US States.

The first chart illustrates states down the left column and across the top, the 20 diseases that most likely kill Americans: ischemic heart disease, lung cancer, road injuries, self-harm, cerebrovascular disease, COPD, drug use disorders, Alzheimer disease and other dementias, colon and rectum cancer, interpersonal violence, lower respiratory tract infections, diabetes, congenital birth defects, neonatal preterm birth complications, chronic kidney disease, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, cardiomyopathy, cirrhosis and chronic liver diseases due to alcohol use, and endocrine, metabolic, blood and immune disorders.

In this chart, green is good for health, signifying lower rates of years of life lost to the disease compared to the mean US rate. Red means the rate of years of life lost is significantly higher than the US mean.

There’s lots of red on the bottom, among the following ten states from the bottom up, Mississippi, West Virginia, Alabama, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Kentucky, Tennessee, South Carolina, and New Mexico,

Green dominates, from the top down to tenth, in Minnesota, California, Connecticut, Hawaii, New York, Massachusetts, Washington, New Jersey, Colorado, and Vermont.

What’s underneath these health outcomes are state and local differences in factors that make health: first, access to quality health care services, complemented by environmental factors and lifestyle behaviors — those social determinants that influence our health more than our genetic code at birth.

The top 20 causes of life-years lost listed above show that lifestyle and environment have so much to do with mortality and quality of life: tobacco use, dietary risks, high body mass index, alcohol and drug use, air pollution, activity all shape individual and public health — the heaviest disease burdens in heart disease, diabetes, and lifestyle-influenced cancers (most notably lung). Then note road injuries, self-harm, drug use disorders, and interpersonal violence — deaths related to safe driving, mental health, physical and personal pain.

The second chart covers years lived with disability — the quality of life stuff, like pain which dominates the list via low back, migraine, and neck. Depression and mental/behavioral health conditions also feature prominently in years lived with disability.

The second chart covers years lived with disability — the quality of life stuff, like pain which dominates the list via low back, migraine, and neck. Depression and mental/behavioral health conditions also feature prominently in years lived with disability.

How to deal with these challenges? The researchers recommend three strategies: first, address key modifiable risks like diet, tobacco, alcohol and drug use, activity, and obesity; then improve access to quality of care in specific areas to address chronic kidney disease and substance use disorders; and, address social determinants of health. The authors have calculated a 74% of overall variation of life expectancy based on socioeconomic and race/ethnicity factors combined with behavioral and metabolic risk and healthcare factors.

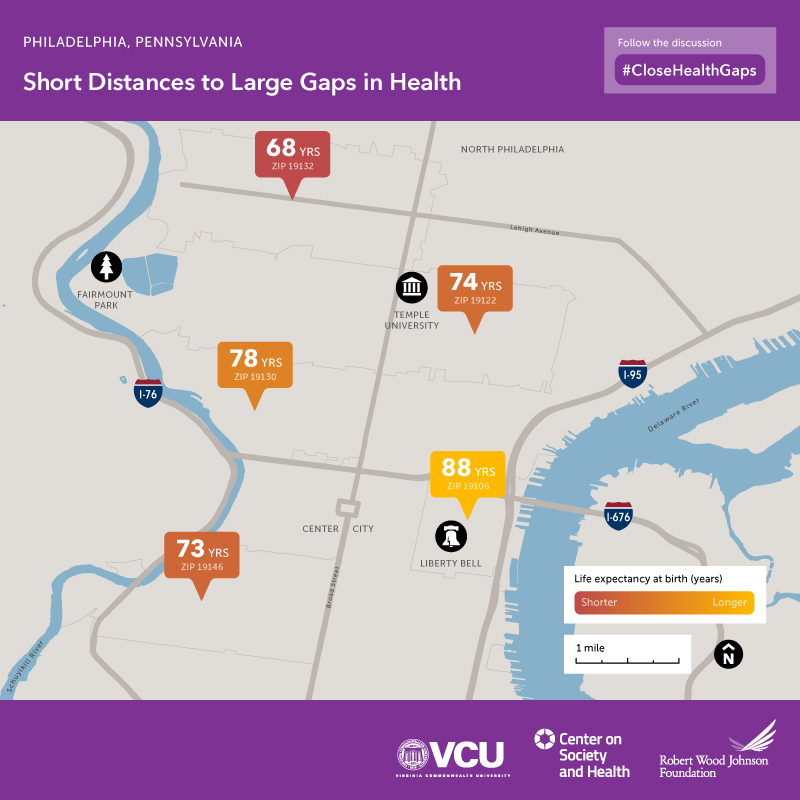

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Public health is personal health at the ZIP code level. Here’s a map of life expectancy in my town of Philadelphia, illustrating that if you live in Philadelphia northeast of Temple University, you are likely to live 20 fewer years than residents who live in Olde City near the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall.

Independence Hall is where the Founding Fathers convened to get to a consensus about Life, Liberty, Pursuits of Happiness, and all Men being Created Equal. Do Americans today believe these concepts extend to health and healthcare?

The evidence in terms of outcomes and the burden of disease by US state demonstrates, “no,” we do not.

The evidence in terms of outcomes and the burden of disease by US state demonstrates, “no,” we do not.

While health care services (both in terms of access and quality) can address some of the variation between health/life have’s and have-not’s in America, those complicated and multivariate social determinants profoundly influence American lives. “To increase the likelihood of prevention to succeed, it has to be a priority for all stakeholders — physicians, nurses, hospital systems, policy makers, health insurance companies, patients and their families, and advocacy groups.”

To succeed, strategies from bake in the notion of accountability broadly beyond “care” to address risk reduction in partnership with patients and communities, the report asserts in its conclusion.

And so back to Independence Hall and the Founders: as Benjamin Franklin said at the time, “You have a Republic…if you can keep it.” The chasm between health have’s and have-not’s threatens the unity, health and wellbeing of the nation.

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a