One-third of Americans are following a specific eating pattern, including intermittent fasting, paleo gluten-free, low-carb, Mediterranean diet, and Whole 30, among dozens of other food-styles in vogue in 2018.

One-third of Americans are following a specific eating pattern, including intermittent fasting, paleo gluten-free, low-carb, Mediterranean diet, and Whole 30, among dozens of other food-styles in vogue in 2018.

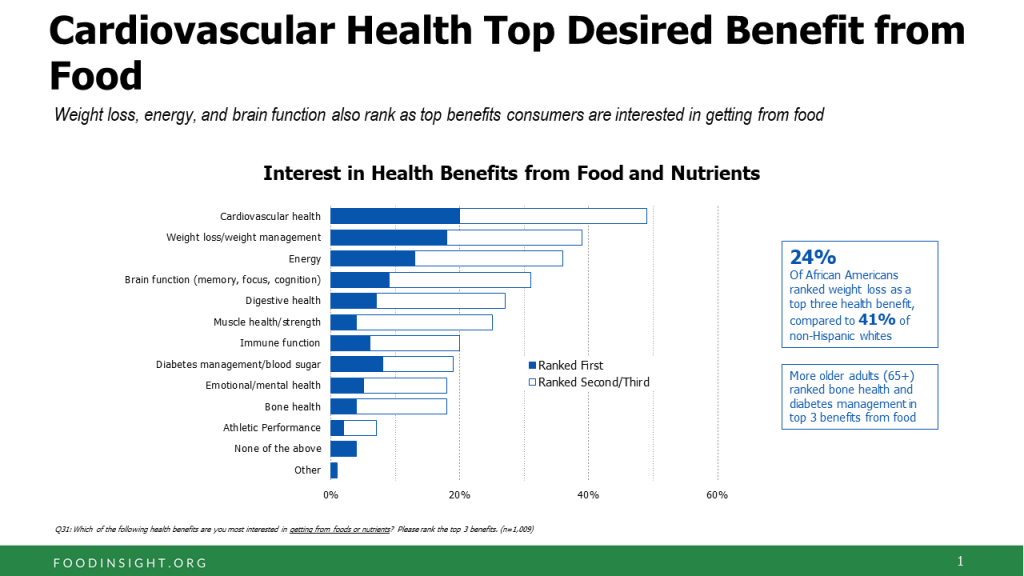

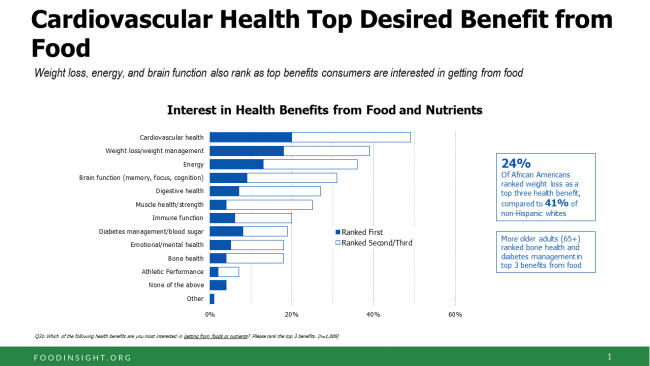

It’s mainstream now that Americans are shopping food for health, with eyes focused on heart health, weight, energy, diabetes, and brain health, according to the 2018 Food & Health Survey from IFIC, the International Food Industry Council Foundation.

But underneath these healthy eating intentions are concerns about the cost of nutritious foods, IFIC reports. And this aspect of home health economics can sub-optimize peoples’ health.

Consider the first graph on consumers’ interests in the health benefits accruing from food and nutrients. Cardiovascular health ranks at the top among one-fifth of people, followed closely by using food with the goal of weight loss and maintaining a healthy weight.

Weight loss, energy, and disease prevention are on a plurality of peoples’ minds when adopting a specific eating pattern like paleo or the DASH diet.

Consumers say the number one food factor is sugar, followed by carbohydrates which are increasingly blamed. 3 in four people are limiting or avoiding sugars in their diet, using tactics like drinking more water than soda or juices and no

Consumers say the number one food factor is sugar, followed by carbohydrates which are increasingly blamed. 3 in four people are limiting or avoiding sugars in their diet, using tactics like drinking more water than soda or juices and no

longer adding table sugar to beverages.

With these good intentions, most people could not connect a food to a health goal. Only one-third of consumers could name a food they would seek for a top

health issue. Among those who could connect these dots, they named protein, vegetables, fruits, and oils.

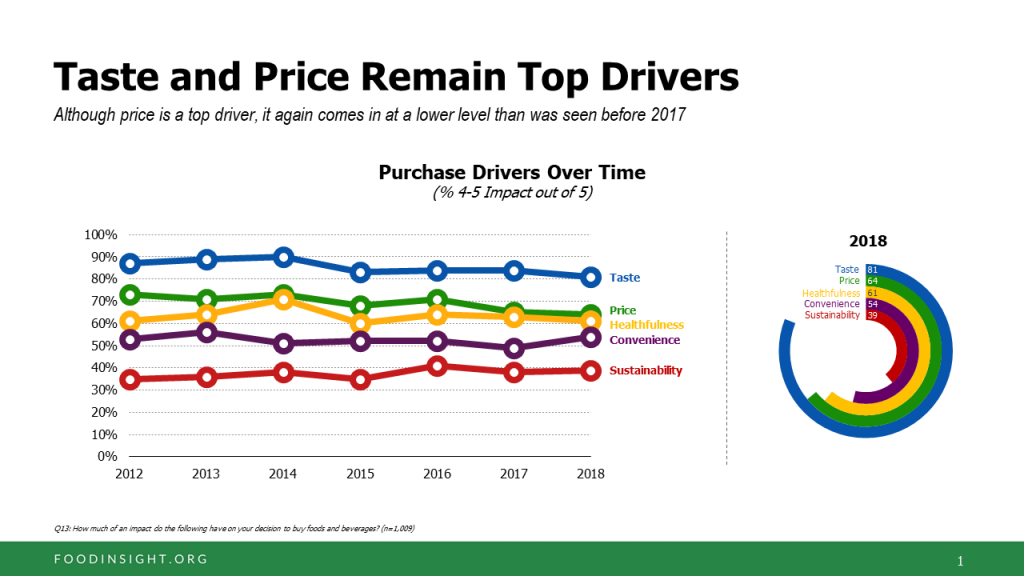

While taste ranks the top purchase driver for food shopping, price and health tie for second-place.

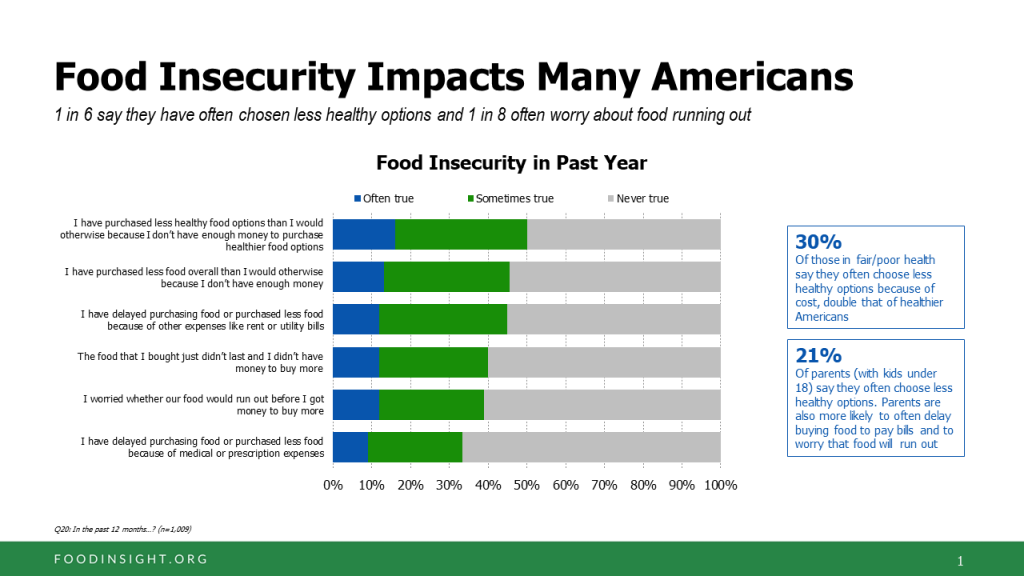

That price issue is central to consumers’ perceptions about their ability to afford healthy food. One-half of Americans have purchased less healthy food than they would otherwise do because they don’t have enough money to buy healthier food options. Nearly 1 in 2 people have also delayed grocery shopping due to other expenses in their household like utility bills and rent, or purchased less food overall because they didn’t have enough money in their budget.

As a direct result of medical or prescription expenses, one-third of Americans delayed buying food or purchased less food, the survey found. Look carefully at this chart on food insecurity.

To mitigate cost challenges for food buying, more than half of Americans use coupons, and nearly half purchase more products on sale. 40% of Americans have cut back on eating out in restaurants, and have shifting purchasing generic or store brands versus brand named products.

More women than men are taking on these cost-cutting strategies to manage food expenses.

IFIC surveyed 1,009 American online adults ages 18 to 80 in March 2018.

You can read my take on IFIC’s 2017 survey here on Health Populi – Shopping Food for Health is Mainstream, but Confusion is Super-Sized.

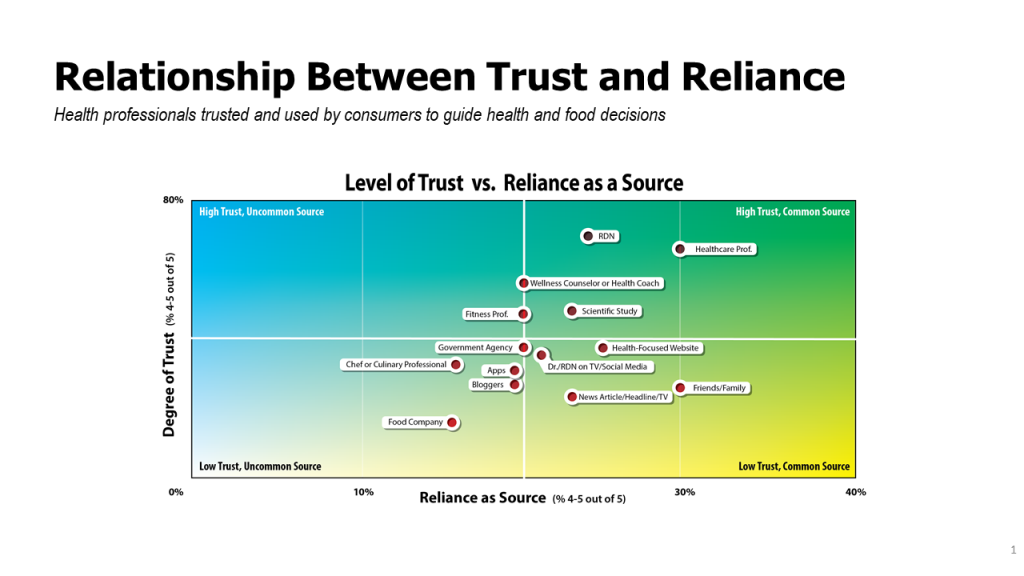

Health Populi’s Hot Points: With consumers focusing their food consumption in the context of their health, it’s important to note that most consumers trust clinical professionals first as sources for what foods to eat or avoid. Registered dietitians and nutritionists, personal healthcare professionals, wellness coaches and reading scientific studies rank at the top as trusted sources of healthy food information. This chart on the relationship between trust and reliance illustrates this issue, with the upper right quadrant of high trust coupled with reliance as a source capturing the evidence-based, clinical value in the eyes of healthy-minded consumers.

This is an opportunity for the legacy healthcare system, hospitals and physicians, to address the food-as-medicine gap that consumers (patients) want and need. IFIC found that 54% of consumers get information from their healthcare professionals, and when doing so, 78% of those consumers made a change like eliminating certain types of foods from their diets or increasing consumption of vegetables.

Clinicians can leverage their trust-factor with patients and in local communities to counsel patients on the food-health opportunity, and work with organizations in their towns to connect people to grocery stores and Big Box retailers as well as food pantries that go that last mile for convenient consumer touch-points.

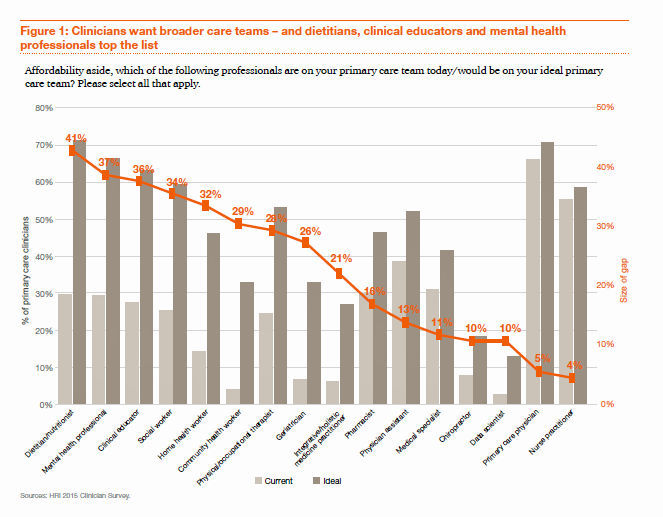

Be aware that primary care providers are already switched-on to this idea. The first employee-hat that primary care doctors would bring on staff if they had resources to do so wouldn’t be another doctor or nurse — that person would be a dietitian or nutritionist, based on a recent PwC survey on re-imagining primary care, Building the Primary Care Dream Team. That individual would be hired ahead of a mental health professional — recognizing that perhaps the obesity epidemic is top-of-mind for clinicians, coupled with behavioral health, as the bar graph suggests.

Be aware that primary care providers are already switched-on to this idea. The first employee-hat that primary care doctors would bring on staff if they had resources to do so wouldn’t be another doctor or nurse — that person would be a dietitian or nutritionist, based on a recent PwC survey on re-imagining primary care, Building the Primary Care Dream Team. That individual would be hired ahead of a mental health professional — recognizing that perhaps the obesity epidemic is top-of-mind for clinicians, coupled with behavioral health, as the bar graph suggests.

Innovative healthcare providers are already on this opportunity, like Geisinger who is working both the precision medicine/genomics technology angle as well as the social determinants of health approach to nutrition through the organizations Fresh Food Farmacy. In Albuquerque, the Presbyterian Kaseman Hospital recently launched a Food Pharmacy, as well, collaborating with the community’s Roadrunner Food Bank to help people better manage chronic conditions.

In October 2018, IFIC will publish a supplement to this report focusing on people enrolled in Medicaid, partnering with the Root Cause Coalition. I look forward to this research, which will be an important contribution to our understanding the cost-health trade-offs people make in daily life which can sub-optimize our individual and community health and wellness.

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a