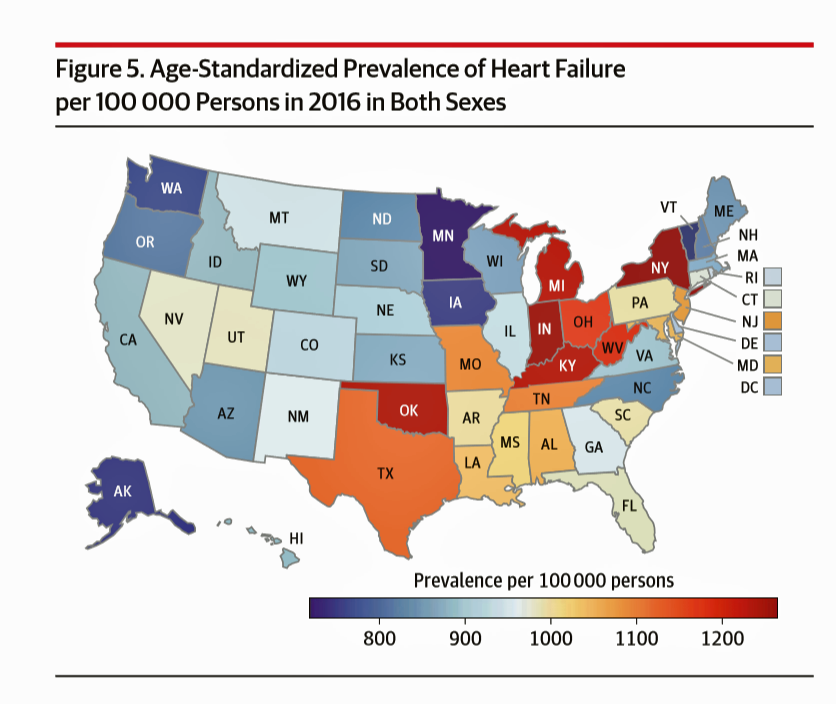

If you live in one of nine U.S. states, your chances of having heart disease are greater than living in the 41 others.

This geography-as-destiny for heart conditions is examined in The Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases Among US States, 1990-2016 published in JAMA Cardiology.

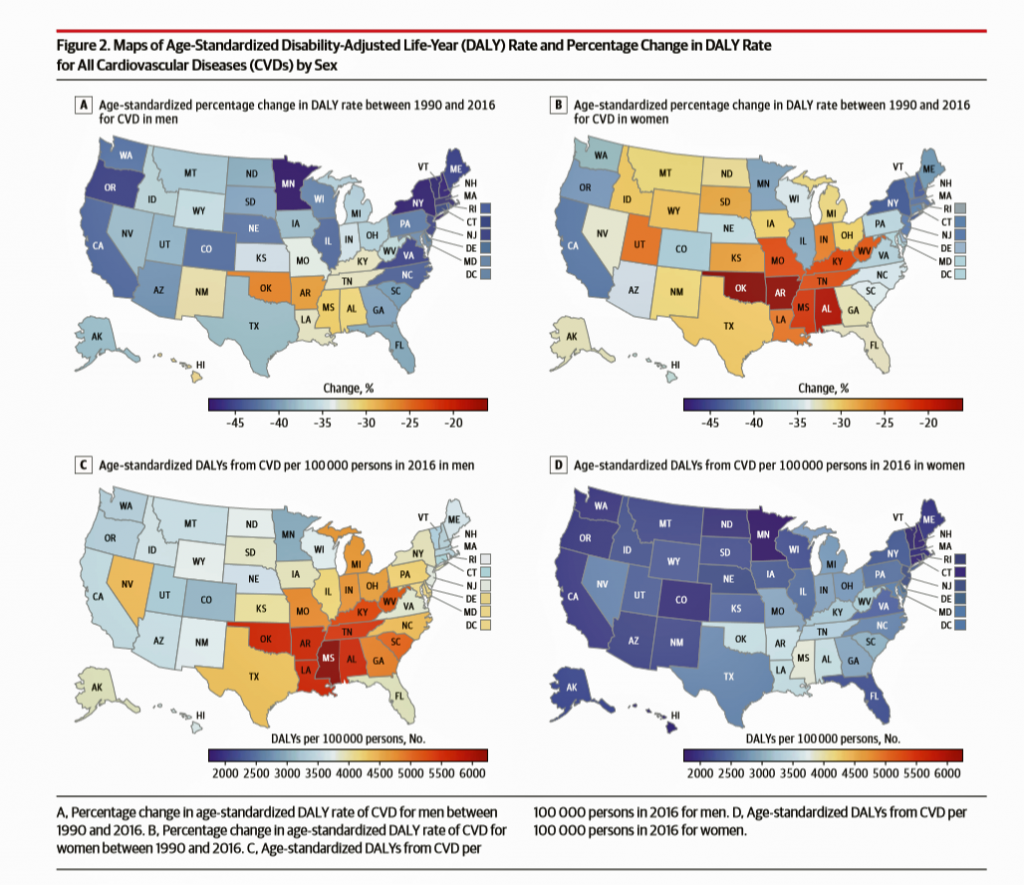

Researchers analyzed data on cardiovascular disease mortality, nonfatal health outcomes, and risk factors by age, sex, and year from 1990 to 2016 for the U.S. population. The outcome used to measure health by state was cardiovascular disease disability-adjusted life-years, or DALYs (FYI, “DALYs” are a commonly used metric in health economics research). Pennsylvania

While overall cardiovascular disease DALYs decreased between 1990 and 2016, nine states’ results increased: Arkansas, Oklahoma, Alabama, Kentucky, Missouri, Indiana, Kansas, Alaska, and Iowa.

Men’s DALY’s for heart disease were twice as great as women’s.

Twelve risk factors were key to CVD DALYs — in particular, dietary risk exposures, high blood pressure, high body mass index (BMI), high total cholesterol, high fasting plasma glucose level, tobacco smoking, and low levels of physical activity.

The study concluded noting that differences in cardiovascular disease are amenable and responsive to behavior change based on the key risk factors.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: We know that geography can be destiny when it comes to understanding peoples’ health status. Look at the Blue Zones project, the Gallup-Healthways Wellbeing Index, the Aetna Healthiest Communities study, et al. Each of these research studies, and others, appreciate the multiple factors that help a person make health. These are the so-called Social Determinants of Health (SDOHs).

”Make health,” indeed, because these factors lie outside of the healthcare system. The JAMA Cardiology study found a deadly dozen risk factors contributing to the rise of cardiovascular disease in nine states. And we know that many of these states have other factors that can negatively influence their health citizens’ health status, like education attainment, lack of Medicaid expansion (for health care services access), and food deserts.

It is encouraging to see new tech efforts emerging to address SDOHs – such as the use of Lyft and Uber to transport patients to healthcare appointments, Amazon extending rime discounts to clients enrolled in Medicaid and SNAP benefits, and good food-as-medicine channeled to folks who need it, such as Geisinger’s Food Pharmacy.

Each of these, in themselves, are good things. But were I Health/care Queen of America, I would rule for a broader, more health-effective, cost-efficient context, embedding health into public policies for a greater and more holistic impact on the public’s health so that, state-by-state, it wouldn’t much matter if I was Alaskan, a Michigander, a New Yorker, or Texan. I’d just be an American Health Citizen.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for