There’s a shortage of medical providers in the United Kingdom, a nation where healthcare is guaranteed to all Britons via the most beloved institution in the nation: The National Health Service. The NHS celebrated its 70th anniversary in July this year.

There’s a shortage of medical providers in the United Kingdom, a nation where healthcare is guaranteed to all Britons via the most beloved institution in the nation: The National Health Service. The NHS celebrated its 70th anniversary in July this year.

The NHS “supply shortage” is a result of financial cuts to both social care and public health. These have negatively impacted older people and care for people at home in Great Britain. This article in the BMJ published earlier this year called for increasing these investments to ensure further erosion of population and public health outcomes, and to prevent further health disparities in the UK.

Along with this provider-supply shortage, the UK recognizes a national social stress for which Prime Minister Theresa May created a Minister for Loneliness post. This initiative resulted in a strategy for tackling loneliness in the United Kingdom.

Here is a snippet from the UK government’s press release last week on the extent of the nation’s social isolation challenge:

“Loneliness is one of the greatest public health challenges of our time, Theresa May said today as she launched the first cross-Government strategy to tackle it.

The Prime Minister confirmed all GPs in England will be able to refer patients experiencing loneliness to community activities and voluntary services by 2023.

Three quarters of GPs surveyed have said they are seeing between one and five people a day suffering with loneliness, which is linked to a range of damaging health impacts, like heart disease, strokes and Alzheimer’s disease. Around 200,000 older people have not had a conversation with a friend or relative in more than a month.

Three quarters of GPs surveyed have said they are seeing between one and five people a day suffering with loneliness, which is linked to a range of damaging health impacts, like heart disease, strokes and Alzheimer’s disease. Around 200,000 older people have not had a conversation with a friend or relative in more than a month.

The practice known as ‘social prescribing’ will allow GPs to direct patients to community workers offering tailored support to help people improve their health and wellbeing, instead of defaulting to medicine.

As part of the long-term plan for the NHS, funding will be provided to connect patients to a variety of activities, such as cookery classes, walking clubs and art groups, reducing demand on the NHS and improving patients’ quality of life.”

This topic set the context for my conversation with Maneesh Juneja, digital health futurist and global speaker on health, technology and people.

I spent time with Maneesh while in London this week. On his way walking to meet me, he shared the above image from his Apple iPhone sent to him through the Hugging Faces chatbot, texted via our WhatsApp connection. I wasn’t surprised that Maneesh was revealing this private message with me, because he is very transparent via social networks on his personal tests and hacks with wearables and apps. Maneesh goes well beyond tracking steps and heart rate: for example, air quality in his immediate environment. [On the morning we met in the café in Covent Garden, the data from his personal air pollution sensor showed very high levels of indoor pollution].

This moment was a different flavor: the Hugging Faces chatbot was speaking about friendship, and Maneesh texted me, “I’m just chatting with my new BFF.”

Now you know something important about this man. He studies digital health passionately, personally, viscerally. He wears many devices at once, putting the techs to his tests, and figuring out just what works well, and for whom.

“For whom” more often than not means those who have been long-overlooked by healthcare providers, technology developers, and public policy: the sicker, the frailer, the disenfranchised, the less affluent, the less educated, the geographically isolated, and folks without broadband access.

“For whom” more often than not means those who have been long-overlooked by healthcare providers, technology developers, and public policy: the sicker, the frailer, the disenfranchised, the less affluent, the less educated, the geographically isolated, and folks without broadband access.

None of these factors is independent of the others for people who may obviously fit into one of them.

That’s why PM May’s public policy prescription has the potential to be so powerful: because the strategy is weaving in loneliness policy across many Ministers’ portfolios along with engaging private sector and NGO involvement.

Tackling loneliness touches on all aspects of daily life: economic, social, environmental, transportation, and to be sure, health and nutrition.

Here’s just one real-life scenario about baking health and social connection into public policy, across government siloes. In the same week as the UK government issued the loneliness strategy, the BBC (Britain’s public service broadcaster, and the world’s oldest national broadcasting organization) said they were evaluating whether to charge people who are over 75 years of age for a TV license. Since 2000, the BBC has offered a free TV license to over-75s which amounts to a £150 subsidy for some 4.5 million people in Britain.

Ironically — and this is where the right hand (call that the BBC idea) doesn’t know what the left hand (the loneliness strategy) is doing.

Here is a UK report from Ofcom (the UK’s communications regulatory agency, akin to America’s FCC) that found that two-thirds of Britons 75 and over would most-miss a TV set versus a mobile phone, radio, or computer.

Thus, the BBC policy of charging elders £150 for the right to watch television — when a TV could be that person’s major social connection to her outside world — would be counter to the isolation policy objectives.

Thus, the BBC policy of charging elders £150 for the right to watch television — when a TV could be that person’s major social connection to her outside world — would be counter to the isolation policy objectives.

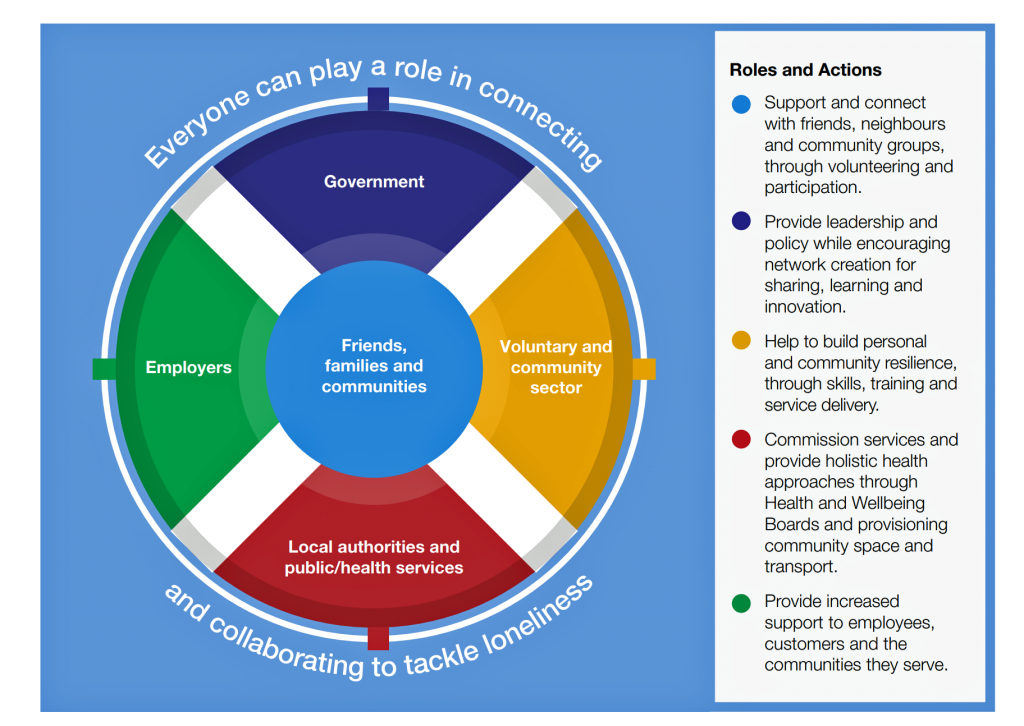

“Everyone can play a role in connecting and collaborating to tackle loneliness,” the circle chart asserts. This graphic is reproduced from the strategy report, and represents the policy’s multi-stakeholder approach to addressing loneliness in the UK: government, employers, local authorities and health services, and community organizations are all named in the report in playing roles. At the center of this convergence are friends, families and peoples’ communities.

These policy recommendations are rooted in a tragedy: the murder of Jo Cox, the Labour MP who was murdered in 2016. Jo had campaigned about loneliness, and had worked with Oxfam for many years. Jo had set up the Commission on Loneliness before she was killed. You can learn more about Jo Cox and the loneliness agenda here.

For further information on loneliness in the UK, here was the New York Times’ take on the appointment of the Minister for Loneliness published in January 2018.

And here is an important essay, quite timely to revisit from 2016, from The New Yorker on Jo Cox, the Brexit Vote, and the Politics of Murder.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Maneesh snapped this photo of us as we were about to say so long, for now, in Covent Garden. In our conversation, we covered a lot of ground — starting and ending with “Cordelia” (the name that the Hugging Faces app chose to name Maneesh’s personal chatbot), AI, virtual friends, friendship, and what it means to be human in the 21st century. And, we talked about the fact that Nigeria will be the third most populous nation in the world by 2050 after China and India.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Maneesh snapped this photo of us as we were about to say so long, for now, in Covent Garden. In our conversation, we covered a lot of ground — starting and ending with “Cordelia” (the name that the Hugging Faces app chose to name Maneesh’s personal chatbot), AI, virtual friends, friendship, and what it means to be human in the 21st century. And, we talked about the fact that Nigeria will be the third most populous nation in the world by 2050 after China and India.

How can we scale health and well-being in a scarce resource world?

We talked about the potential for AI and data (the right data, not just all “Big Data,” to include linked and longitudinal data) to augment healthcare providers in terms of both sheer supply and geographic access. The NHS is always resource-constrained as it operates on a budget; for Americans, think about how difficult and/or painful the migration from volume-based payment to value has been. The NHS has never known about volume-based payment, which I learned on a steep learning curve when I worked in London and through the UK NHS regions over two decades ago. That’s when, here in the UK, I cut my own professional teeth on the role of health IT to help measure and manage health care resources, quality and patient outcomes under severe resource constraints.

With technology enablers like the cloud, wearable tech, and broadband, we have the potential to scale health and care to people who haven’t benefited from access to mental health and social services, tertiary and specialist care, and social connectivity via online patient groups.

With technology enablers like the cloud, wearable tech, and broadband, we have the potential to scale health and care to people who haven’t benefited from access to mental health and social services, tertiary and specialist care, and social connectivity via online patient groups.

I leave you with a sentence from May’s introduction to the loneliness strategy report: “For one of the best ways of tackling loneliness is through simple acts of kindness, from taking a moment to talk to a friend to helping someone in need.”

Building mental models and sharing perspectives with Maneesh was a moment of both learning and of kindness. It will take a village to help us make healthcare better, and to address loneliness. I’m so grateful and comforted to know Maneesh is on the march with me.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for