As more mobile app users — consumers, patients, and caregivers — use these handy digital health tools, much of the data we share can be re-identified and monetized by third parties well beyond those we believe we’re sharing with.

As more mobile app users — consumers, patients, and caregivers — use these handy digital health tools, much of the data we share can be re-identified and monetized by third parties well beyond those we believe we’re sharing with.

This compromised health data privacy scenario comes out of research published this month in the BMJ, Data sharing practices of medicines related apps and the mobile ecosystem: traffic, content, and network analysis.

The researchers, faculty from the University of Toronto (Canada) and the University of Sydney (Australia), come from nursing, pharmacy, and computer science expertise — a sound combination of disciplines to ask the question, “how are consumer data shared by top rated medicines related mobile apps,” and to assess the privacy risks to app users. The authors look through both clinician and consumer lenses.

The research identified top-ranked health-related apps for Android mobile platforms available in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the U.S. The analysis started with 821 apps found through a crawling program and expert sources, and narrowed that app universe down to 24 unique apps for the analysis: 10 targeting health professionals, 11 focused on consumers, and 3 targeting both user-types.

The researchers then looked into the data transmitted to third parties among these apps, including the type of consumer data, volume of those transmissions, and the identities of the third parties with whom consumer data were shared.

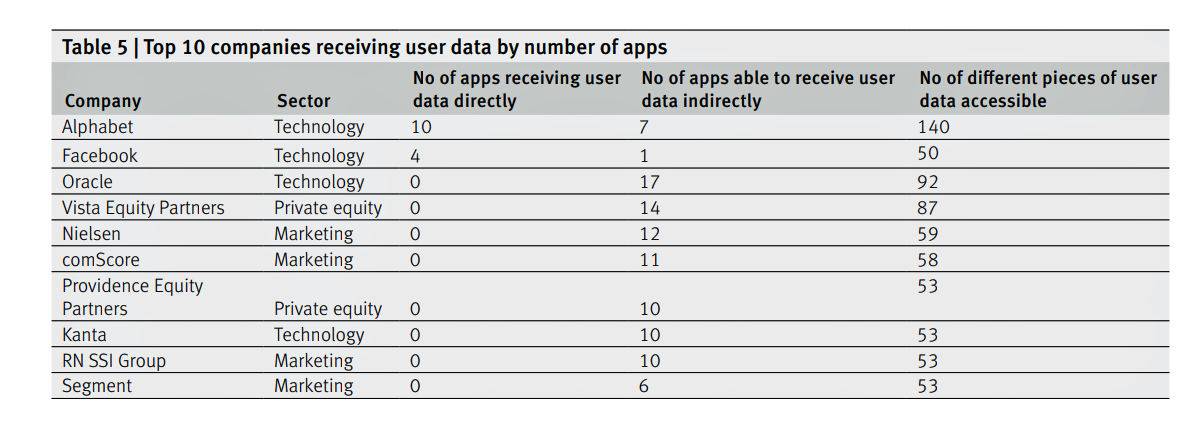

The first chart summarizes the top ten companies that received user data by the number of apps and pieces of user data. By far, the most active third party receiver was Alphabet/Google. Other companies trailed behind Google including Facebook, Oracle, Vista Equity Partners, Nielsen, and comScore.

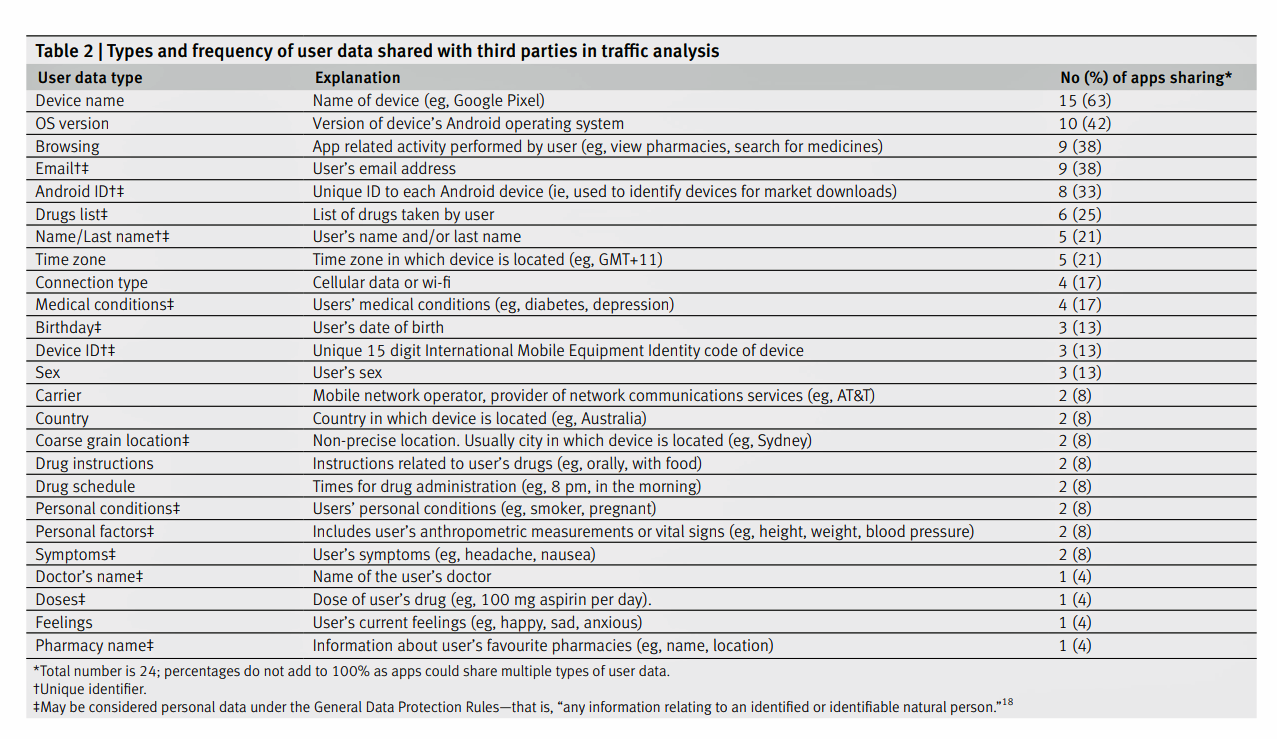

The second chart inventories the types and frequency of user data shared with third parties. The most common data types were device names, version of the operating system used, browsing history (e.g., pharmacies, prescription drugs), email addresses, and drug lists. User names were identified by one in five apps studied.

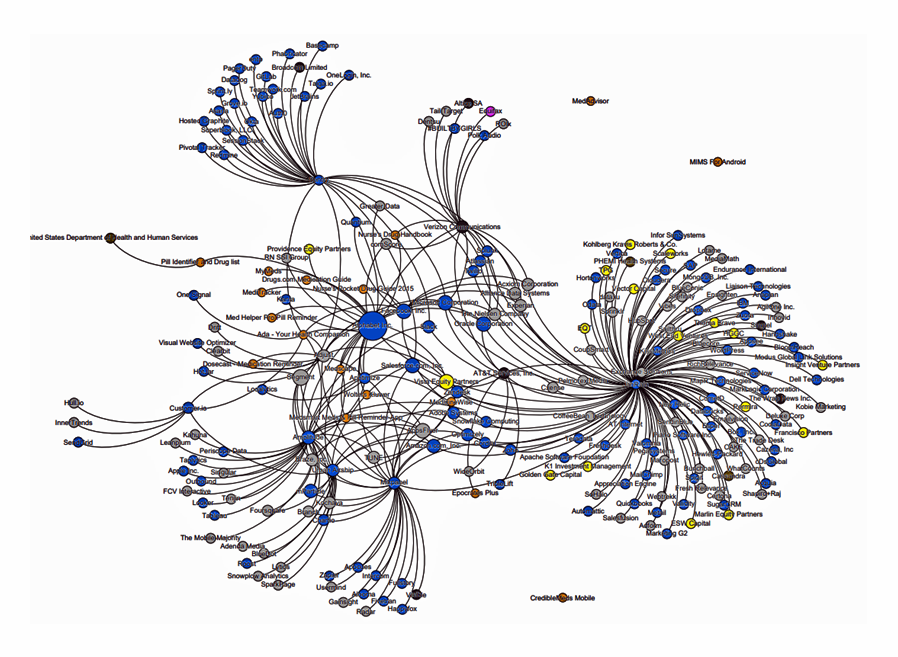

Beyond this third-party data analysis, the research identified fourth-party sharing in the mobile app ecosystem. Companies in the fourth party network receive consumer data for behavior analytics and advertising, among other applications, the article notes. The third graphic represents the fourth party data network of 237 entities — 17 app families, 18 third parties, and 216 fourth parties. The blue dots are typically software and technology companies (about 55% of the entities); the grey dots are digital advertising companies. Only three entities were related to healthcare (the brown dots).

Beyond this third-party data analysis, the research identified fourth-party sharing in the mobile app ecosystem. Companies in the fourth party network receive consumer data for behavior analytics and advertising, among other applications, the article notes. The third graphic represents the fourth party data network of 237 entities — 17 app families, 18 third parties, and 216 fourth parties. The blue dots are typically software and technology companies (about 55% of the entities); the grey dots are digital advertising companies. Only three entities were related to healthcare (the brown dots).

The prevalence of Google in this ecosystem is a key finding from the study. The authors call out that Alphabet, the parent company of Google, owns the third parties Crashlytics, Google Analytics, and AdMob By Google which were all in the ecosystem studied. In the company’s privacy policy Google reports data sharing partnerships with Nielsen, comScore, Kanta and RN SSI Group.

Beyond Google (Alphabet), the authors identify Facebook and Verizon Communications as “having received monopoly positions within the mobile ecosystem.”

The bottom-line conclusion: the collection of app users’ data is a business, but the lack of transparency and less-than-tenacious approach to securing users’ consent doesn’t benefit the consumer, the authors assert. They believe that users can be easily identified.

“Currently, within the ‘big data’ industry, users do not own or control their personal data,” the researchers conclude. “Regulators should focus on full transparency, requiring sharing as opposed to privacy policies…privacy will become an important social determinant of health.”

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I wrote Here’s Looking at You on behalf of the California Healthcare Foundation (CHCF) in July 2014, highlighting how third parties could access and mash-up data generated through digital tools — both consumer apps and health-focused ones, along with retail receipts and social network check-in’s.

The BMJ study is a welcome update to my work, especially as more consumers download and use mobile apps in daily life-flow, for managing both everyday life and, increasingly, to support their own and loved ones’ health. Consider the growing Internet of Things for health/care, connected car concepts baked with wellness, and the advances in voice tech that Alexa and her cousins from Google and Samsung are making to support our health at home and in that automobile. All of these new-new “things” are connected devices, generating personal data that can be scraped for our health profiles.

While California will implement a broad consumer-protective privacy law on January 1, 2020, the remainder of the U.S. remains covered by a patchwork quilt of laws that done comprehensively cover American health citizens. Congress is, currently, wrestling with creating an updated privacy law after more than a decade of Americans’ ubiquitous smartphone and social network adoption. Europe’s GDPR is widely recognized as the gold standard for privacy law. Will Americans benefit from a U.S.-style GDPR? Our digital life- and health-styles require that level of personal data ownership, control, and stewardship.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for