“How should we define ‘health?'” a 2011 BMJ article asked. The context for the question was that the 1948 World Health Organization definition of health — that health is, “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”– was not so useful in the 21st century.

“How should we define ‘health?'” a 2011 BMJ article asked. The context for the question was that the 1948 World Health Organization definition of health — that health is, “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”– was not so useful in the 21st century.

The authors, a global, multidisciplinary team from Europe, Canada and the U.S., asserted that by 2011, human health was marked less by infectious disease and more by non-communicable conditions that could be highly influenced, reversed and prevented through self-care by the individual and public health policy that promotes social and financial wellness.

Eight years later, in May 2019, I read Reimagining Health – Flourishing in the 7th May 2019 issue of JAMA with some feelings of déjà vu.

In this essay, three faculty members from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health adopt a patient lens on personal health, observing that: “a patient cares not only about physical health and test results ‘within normal limits’ but also more broadly about being happy, having meaning and purpose, being ‘a good person,’ and having fulfilling relationships.”

That means that meaningful outcome measurements in healthcare should include metrics that people value beyond the raw statistics of, for example, life expectancy at birth and BMI.

The authors make the case for adopting the context of “flourishing” to reframe how we track the peoples’ well-being. Flourishing by definition means “to grow” or “to prosper.” These verbs buttress a new approach known as the flourishing index, developed by Dr. Tyler VanderWeele, one of the report’s authors. Dr. V wrote up the concept in a 2017 article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS).

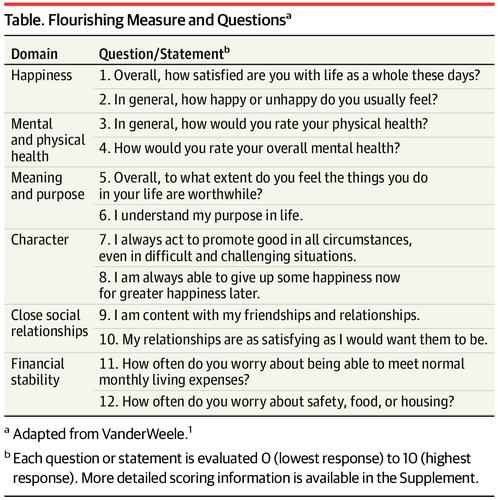

The flourishing index, detailed above in the boxed graphic from the JAMA Viewpoint, looks at six areas that together paint a holistic picture of a person’s wellness: happiness, mental and physical health, meaning and purpose, character, close social relationships, and financial stability.

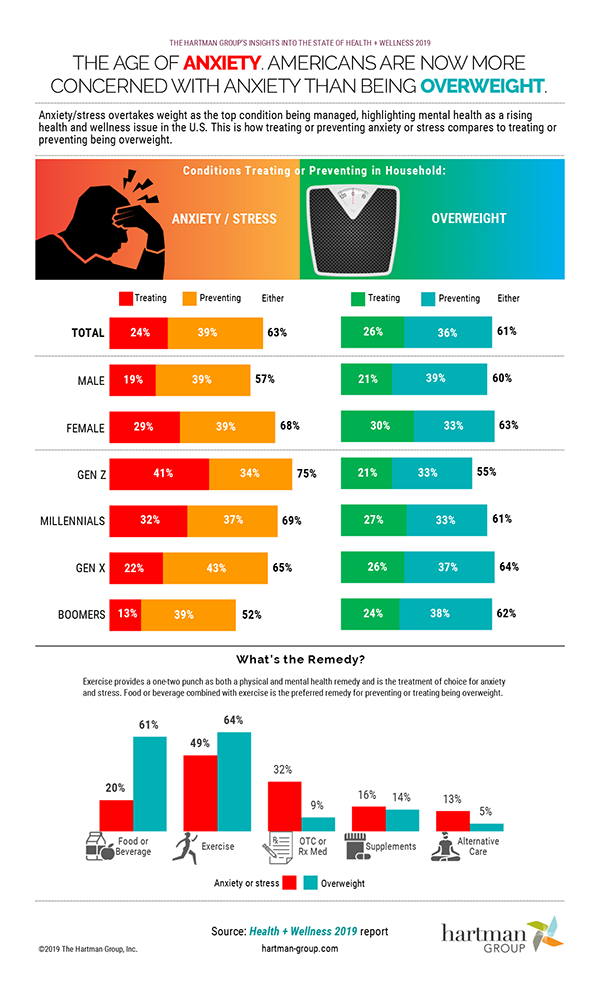

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Two top-of-mind health issues Americans prioritize in 2019 are weight management and anxiety (and other mental health conditions). An infographic from the Hartman Group published in May 2019 examines consumer households’ treatment of anxiety and stress compared to overweight.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Two top-of-mind health issues Americans prioritize in 2019 are weight management and anxiety (and other mental health conditions). An infographic from the Hartman Group published in May 2019 examines consumer households’ treatment of anxiety and stress compared to overweight.

Note that marginally more Americans were dealing with anxiety and stress (63%) than overweight (61%) based on Hartman’s research from their 2019 Health + Wellness report. Hartman unveiled some important demographic differences between the two conditions: more women than men, as well as more younger people, are treating or trying to prevent anxiety/stress. Overweight treatment and prevention demographics are less differentiated, except for younger people relatively less inclined to be concerned about weight.

With this in mind, now consider the disconnect Kaiser Family Foundation focus groups identified in the past week between how Americans feel about “their” health care versus how inside-the-Beltway Capitol Hill legislators and Democratic Presidential candidates stand on health reform proposals.

In this brief Axios explanation, Kaiser Family Foundation’s Drew Altman noted that voters in focus groups (conducted in Florida, Pennsylvania and Texas) see health care as a key voting issue for 2020.

But KFF’s bottom line from these focus groups was that none of the proposals people have heard about truly touched folks and their daily lives.

In that same JAMA issue as the “Flourishing” essay, you’ll find a piece by Andy Slavitt on Doing Health Reform Better: Listening to the Public.

“Most of people’s health care concerns are basic and existential….it’s a far more primal topic than what taxes they pay….When listening to people, one should avoid the temptation of simply clustering their responses and instead pay attention to how specific and idiosyncratic people’s concerns are,” Slavitt recommends.

With that in mind, the JAMA “Flourishing” authors’ last sentence resonates so well: that the flourishing approach, “could open a national conversation that reframed and reimagines traditional concepts of health.”

And I daresay, health reform. As I write in HealthConsuming: From Health Consumer to Health Citizen, “public health is personal at the ZIP code level.” That national conversation on how we can bolster health is also a profoundly personal and community one, as well.

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a