When you think “J.D. Power,” your mind probably imagines reviews of automotive performance, retail shopping experiences, or perhaps even health insurance plan customer service.

Expanding its report-card role in the health ecosystem. J.D. Power has undertaken a survey on consumer satisfaction with 31 telehealth providers across 15 measures, which will be published in November 2019. In advance of the full report, the organization released a summary on telehealth access and satisfaction, which I’ll discuss in this post. I’ll also weave in the latest insights from the ATA 2019 State of the States report updating legislative/regulatory telemedicine activity at the U.S. State level.

Expanding its report-card role in the health ecosystem. J.D. Power has undertaken a survey on consumer satisfaction with 31 telehealth providers across 15 measures, which will be published in November 2019. In advance of the full report, the organization released a summary on telehealth access and satisfaction, which I’ll discuss in this post. I’ll also weave in the latest insights from the ATA 2019 State of the States report updating legislative/regulatory telemedicine activity at the U.S. State level.

For this research, J.D. Power polled 1,000 consumers in June 2019.

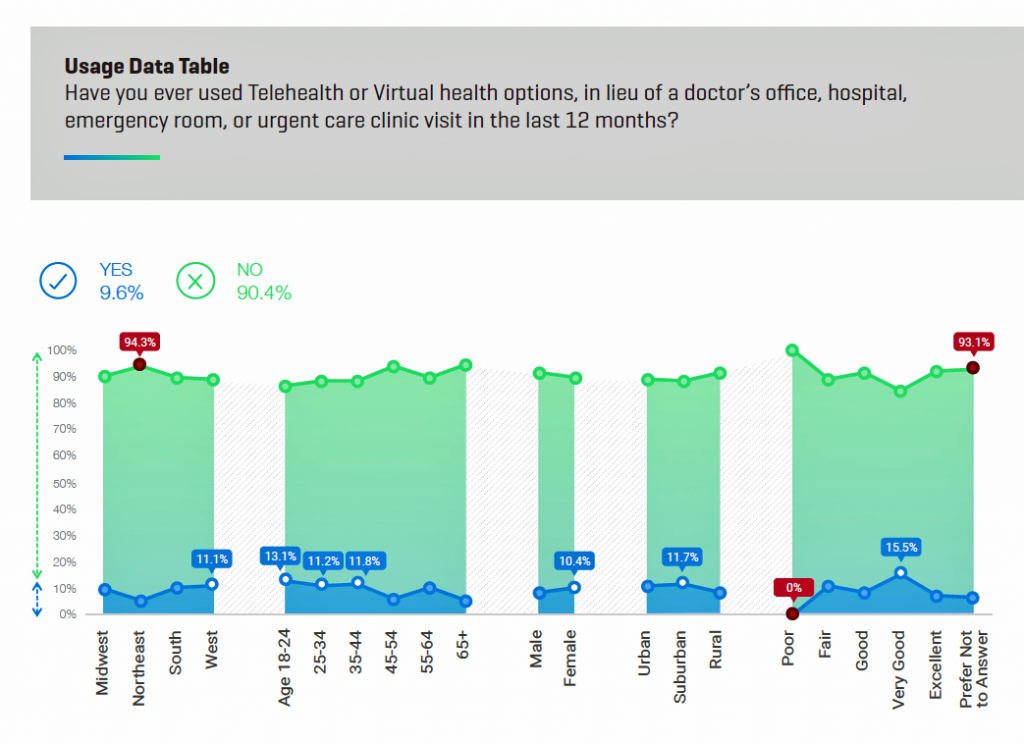

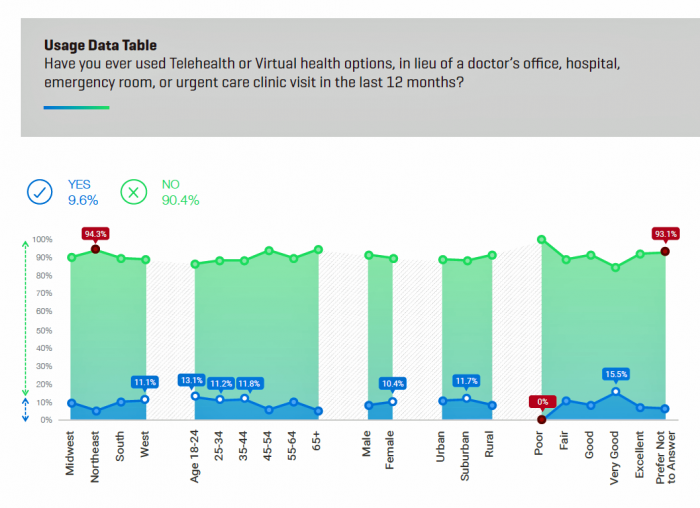

The top-line finding from J.D. Power is that only one in ten Americans have ever used telehealth or virtual health to substitute for an in-person visit to a doctor’s office, hospital, ER or urgent care clinic in the past year. Those who had a telehealth encounter more likely lived in the Western U.S., were under 44 years of age, women more than men (much of this driven by moms caring for children and pediatrics access during off-hours), and suburban dwelling.

It’s not for lack of availability that people don’t use telehealth services: people lack awareness of the availability of providers and health plans’ coverage of virtual care. Three in four people said their health system or health plan did not offer telehealth services or they were unaware of it. There was a markedly high level of unawareness of telehealth in rural areas, which are underserved by health care and a key focus of opportunity for virtual services.

17% of people were aware that their health system or insurance plan offered telehealth or virtual health to substitute for a visit to a hospital, doctor’s office, ER or urgent care site.

17% of people were aware that their health system or insurance plan offered telehealth or virtual health to substitute for a visit to a hospital, doctor’s office, ER or urgent care site.

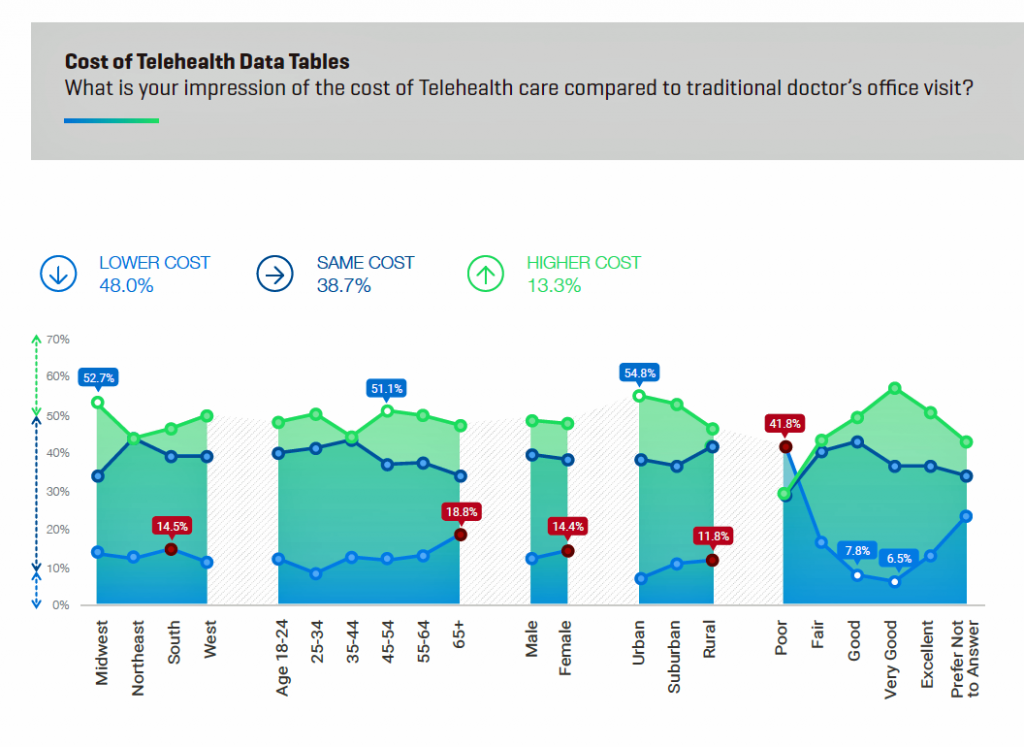

Cost is a key driver for patients seeking health care — often leading to self-rationing or postponing visits to a health care provider when care is needed. One-half of U.S. consumers view telehealth is the same or higher cost; one-half sees telehealth as being lower cost than a traditional doctor’s office visit, shown in the second chart.

One finding worthy of call-out from the second chart on telehealth costs is the data point of consumers who rate the telehealth visit as “very good” or “excellent” who also perceive the visit as higher cost. Here, those consumers are marrying the concept of higher cost with higher quality, which is a perception/myth that ATA and the telehealth industry have been working to debunk.

Now that we’ve looked at J.D. Power’s lens on the consumer/patient demand side for telehealth, let’s examine ATA’s latest read on payment and regulatory issues across the states.

ATA’s 2019 report profiles each state’s approach to telehealth policies by patient setting, payor type, and delivery models, along with providing specific legislation and policies that can dramatically vary state-by-state. In the words of the report, “our analysis reveals a mix of strides and stagnation in state-based policy despite decades of evidence-based research highlighting positive clinical outcomes and increasing telehealth utilization.”

All 50 state Medicaid agencies have adopted some coverage for telehealth, with 10 states not advancing coverage since 2017. There’s a move among state Medicaid programs to migrate from traditional hub-and-spoke models of care, with 29 states not specifying a specific patient setting for payment. Twelve states identify the home as an originating site, and 12 states and Washington DC look to schools as an originating site. Some states recognize both the home and school for telehealth payment.

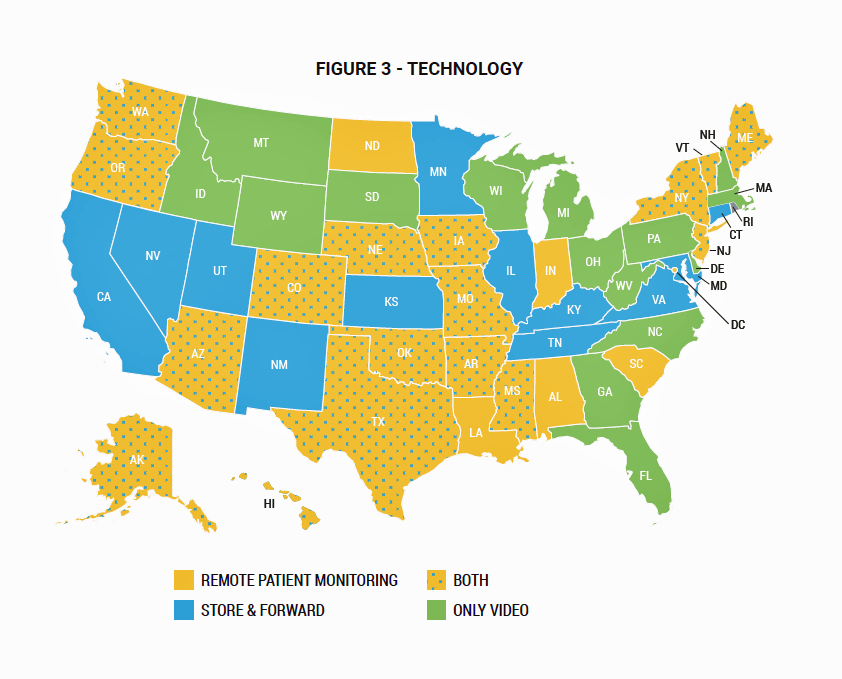

Twenty-two states are covering remote health monitoring and 29 states and the District of Columbia cover services via store-and-forward. One-third of the states cover telehealth via synchronous (real-time) channels, and a few for only video visits. These technology differences are shown in the map shown here from the ATA report.

Twenty-two states are covering remote health monitoring and 29 states and the District of Columbia cover services via store-and-forward. One-third of the states cover telehealth via synchronous (real-time) channels, and a few for only video visits. These technology differences are shown in the map shown here from the ATA report.

An important value of telehealth is its ability to channel care to people living in remote and health care under-served areas. Over half of the states and DC now cover telehealth services provided by a provider of any type beyond a licensed physician. Alabama is the only state that identifies physicians as a telehealth-eligible provider.

Coverage parity is an important issue: that is, whether a health plan or payer will treat telehealth visits as in-person visits in terms for payment. In 2019, 28 states have payment parity policies for Medicaid. Thirty-six states and DC have coverage parity policies for private payers.

As you read my summary of the ATA state-by-state analysis, you would be right to get the impression that telehealth policy in the U.S. continues to be a patchwork quilt based on the ZIP code where a person lives portending what kind of telehealth services will be reimbursed, what type of provider will be involved in the consultation, where the visit will occur, and who the third party payer is.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The reports from J.D. Power and the ATA illustrate the fragmented nature of telehealth in America in 2019. This, notwithstanding a private sector driving innovations and supply in telehealth services in pharmacies, in hospital systems, in schools, and via direct-to-consumer models to the home and smartphone.

There’s a growing trend in direct-to-consumer telemedicine companies recently noted in JAMA in a viewpoint titled, “Prescriptions on Demand.” Dr. Ateev Mehrotra, one of my go-to experts on retail health, and colleagues from Harvard, note that DTC telemedicine companies focus on delivering convenience to patients in a complex health care system as a value-add in the current “consumer-directed” environment. Other advantages offered by DTC telemedicine include standardized, efficient, and accessible care compared with traditional visits to doctor’s offices, hospital clinics, and ERs. And cost, to both the end-user patient and plan-sponsor, is clearly a potential advantage.

There’s a growing trend in direct-to-consumer telemedicine companies recently noted in JAMA in a viewpoint titled, “Prescriptions on Demand.” Dr. Ateev Mehrotra, one of my go-to experts on retail health, and colleagues from Harvard, note that DTC telemedicine companies focus on delivering convenience to patients in a complex health care system as a value-add in the current “consumer-directed” environment. Other advantages offered by DTC telemedicine include standardized, efficient, and accessible care compared with traditional visits to doctor’s offices, hospital clinics, and ERs. And cost, to both the end-user patient and plan-sponsor, is clearly a potential advantage.

But Dr. Mehrotra and team also note that these new treatment options that ensure convenience must, in their words, “not come at the expense of quality.”

Rite Aid is the latest among the retail pharmacy chains to announce a telehealth partnership with InTouch Health via the RediClinic Express kiosks. This service will enable consumers shopping in a Rite Aid store to speak with RediClinic clinicians in a two-way high-def audio/video network.

With the patient-as-payer in the current U.S. health ecosystem, cost/price of health care underpins how, when and where people seek care. FAIR Health’s paper on A Multilayered Analysis of Telehealth published in July 2019 found that telehealth usage has substantially grown since 2015 as more states implement laws for coverage.

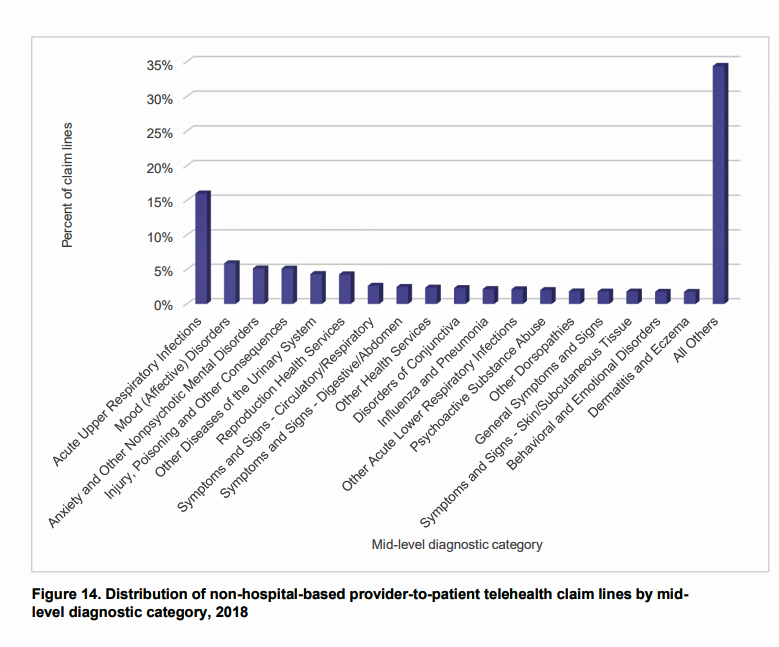

An intriguing data point comes in Figure 14 on the distribution of non-hospital-based provider-to-patient telehealth claim lines in 2018. I’ve copied the chart here.

After the most common patient diagnosis, acute upper respiratory infections (historically the most common complaint presenting in retail clinics), the second and third most frequent reasons for telehealth diagnoses were for mood/affective disorders and anxiety and other nonpsychotic mental disorder. That is, mental health issues.

This finding is a wake-up call, thanks to FAIR Health, illustrating the power of telehealth for mental health. I addressed this as an emerging opportunity in 2012 in The Online Couch, a report I wrote for the California Healthcare Foundation documenting the need and growing supply side for telemental health services. As we know that mental health should be baked into primary care, telehealth channels that demonstrate evidence-based approaches and credentialing can and should help foster that under-served demand in the currently, tragically fragmented U.S. health care system.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for