As large employers’ annual health care costs for an employee are expected to exceed $15,000 in 2020, companies are focusing in on managing the pharmacy line-item, we learn from the 2020 Large Employers’ Health Care Strategy and Plan Design Survey from the National Business Group on Health (NBGH).

I covered large employers’ perspectives and future plans to deal with health care services for workers in 2020 in Health Populi here earlier this week. In this post, I’ll dive deep into the study’s Section VII on Pharmacy Costs and Strategies.

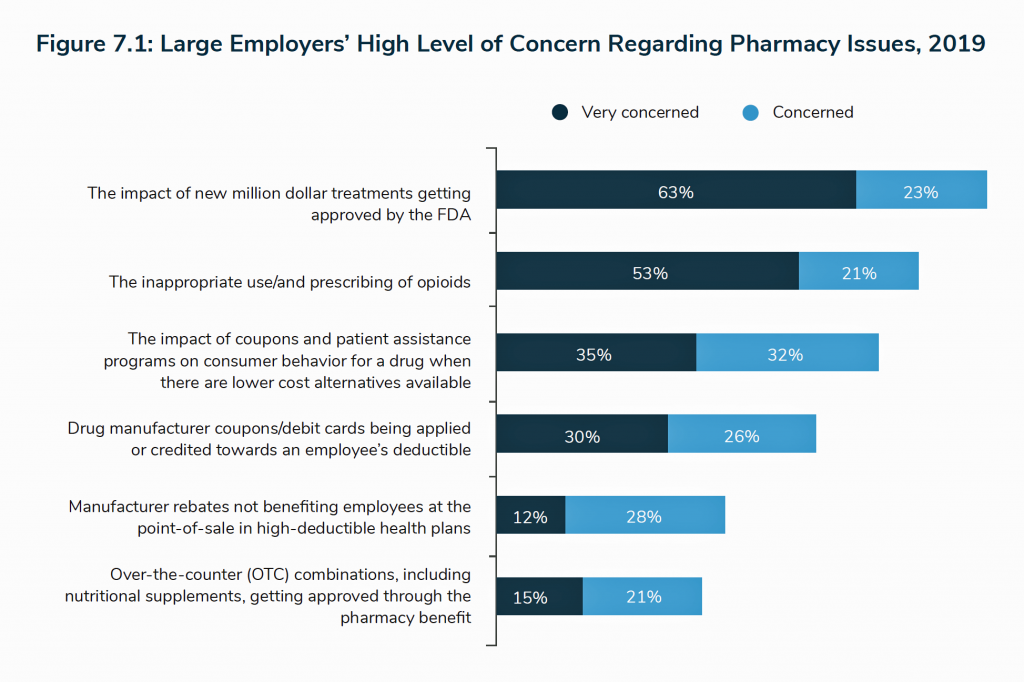

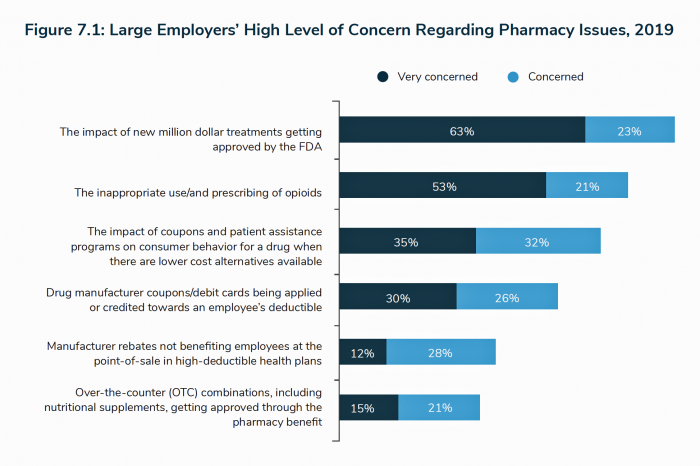

Employers’ most daunting challenge and uncertainty when it comes to dealing with pharmacy spending is the specialty drug impact — specifically, new million-dollar therapies getting approved by the FDA.

Examples of these in the current news cycle are Zolgensma, which is priced about $2 million to treat spinal muscular atrophy, and CAR-T therapy which can run as high as $1 million all-in for the treatment and hospital service costs for the patient.

Eight in ten employers are concerned about new high-cost therapies (generally considered “specialty drugs) that the FDA is expected to approve in the next few years as these medicines come out of the research pipeline into commercial launch phase.

Opiods are the second- most concerning pharmacy issue, for three-quarters of large employers, followed by the impamct of coupons and patient access programs on consumer behavior when lower-cost alternatives are available in the market.

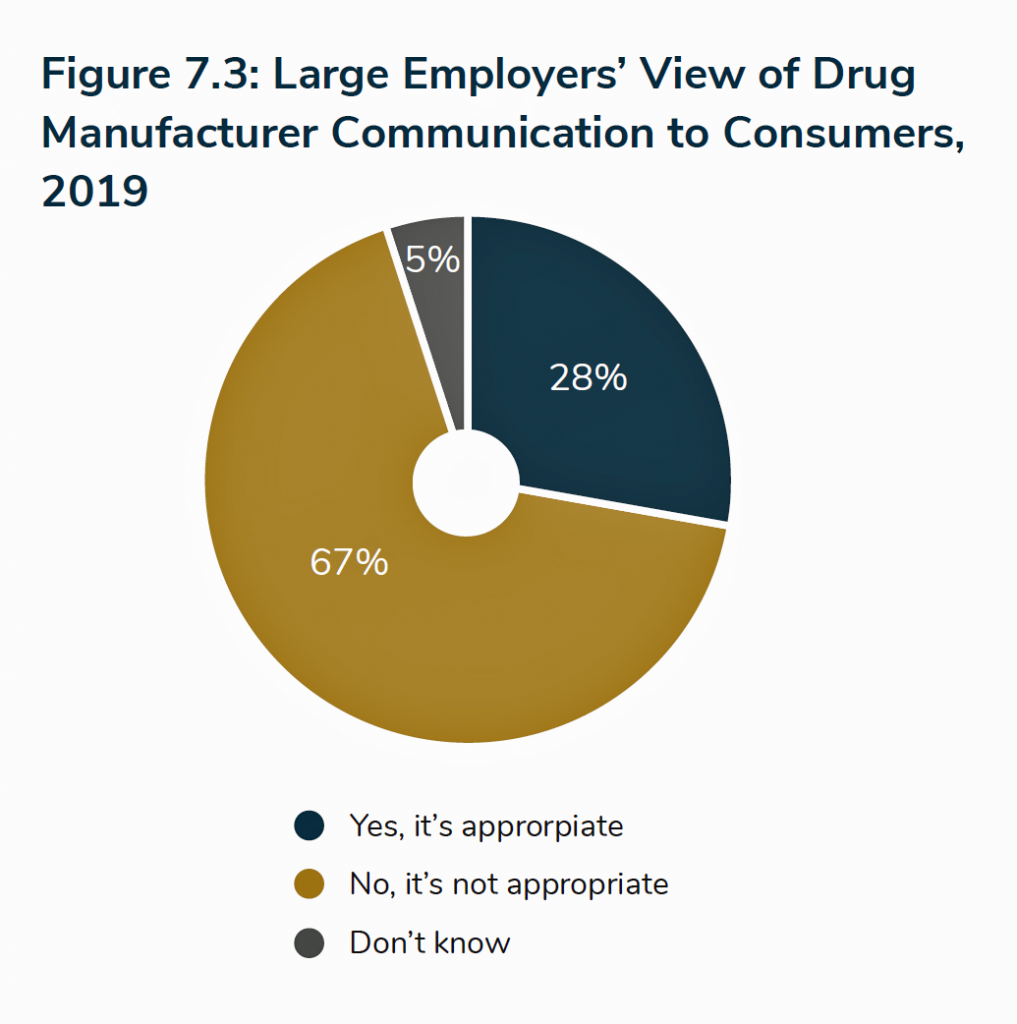

This third point brings up the finding in the second pie chart: that two in three large employers believe that direct-to-consumer advertising (DTC) is inappropriate. This is a huge issue for pharma companies because DTC ads for prescription drugs are legal only in the U.S., unique among all the developed countries in the world with the exception of New Zealand.

This third point brings up the finding in the second pie chart: that two in three large employers believe that direct-to-consumer advertising (DTC) is inappropriate. This is a huge issue for pharma companies because DTC ads for prescription drugs are legal only in the U.S., unique among all the developed countries in the world with the exception of New Zealand.

DTC promotion is a big industry in the American health care ecosystem: pharma companies spend over $6 billion on DTC ads for drugs, compared with half that amount (about $3 billion) by health care providers promoting health care services directly to consumers. Medical marketing, and particularly pharma marketing, is a major business in America and big slice of the “Mad Men” advertising industry.

Among large employers who fell into the 28% of companies that thought DTC communication was indeed appropriate, acceptable topics for comms were medication side effects and indications of the drug. What wasn’t seen as acceptable topics for communicating DTC were patient assistance programs.

After “costs” and “communication” was a third “C” of concern among large employers vis-a-vis prescription drugs: that was the impact of drug coupons. Employers cited several main tactics to address coupon cards looking forward from 2019 to 2022. The top tactic employers identified to manage their concerns about coupons was to review coupon utilization data with the company’s pharmacy benefit manager (PBM). One-third of employers were already doing this in 2019, with another 20% adding in 2020 and 16% considering for 2021-22.

34% of employers are already using a copay card accumulator program that does not allow manufacturer coupons or copay cards to count toward the employee’s dedutible and out of pocket maximum costs. Some 15% of companies will consider this tactic in 2021-22.

Several other areas for dealing with coupon cards will be considered in 2021-22 including education campaigns to help workers understand the costs and benefits of coupons; copay “maximizer” programs that work with patients to take advantage of manufacturer coupns for high-cost drugs, copay card accumulator programs for special drugs only; and, not covering medications that include a consumer coupon when a lower-cost therapy is available.

Co-pay accumulators are being discussed across health plan types, including government-sponsored plans like Medicare along with commercial health insurance programs. This mechanism prevents a co-pay card or funds from a patient assistance program that discount the patient’s drug(s) to be applied to a deductible. In the NBGH survey, 34% of large companies have adopted co-pay accumulator programs that don’t allow manufacturer coupons or copay cards to count toward the workers’ deductibel and out of pocket maximum; another 19% are either adding in 2020 or considering in 2021-22.

As you would imagine, there has been quite a lot of push-back against co-pay accumulators, particularly from patient advocates and organizations who say these programs are essentially a way to shift costs onto sicker people (in this case, the employees who are dealing with acute or chronic conditions).

In addition to co-pay accumulators, the topic of rebates is on the front-burner of large employers. Typically, rebates are paid by a pharmaceutical manufacturer to a pharmacy benefits manager (PBM), who shares a portion of the rebate monies with the health plan or employer (as a self-insured health plan).

Large companies have begun to view the rebate funds at the patient’s point-of-sale (POS), shown in the pie chart.

A POS rebate passes the rebate to a patient-consumer at the point-of-sale when filling a prescription — thereby sharing the incentive payment with the worker who is the end-user consumer of the prescription drug. (In contrast, employers have used rebate payments to defray premium costs).

18% of large eployers offered rebates at POS in 2019, and 40% are considering incorporating this patient-Rx payment tactic in 2021-22.

In addition to considering POS rebate programs, most employers like the idea of a “net price model” of drug costs to the patient. This is based on the net price of medicines with no rebates — and is part of a U.S. Federal government Blueprint for reducing prescription drug costs.

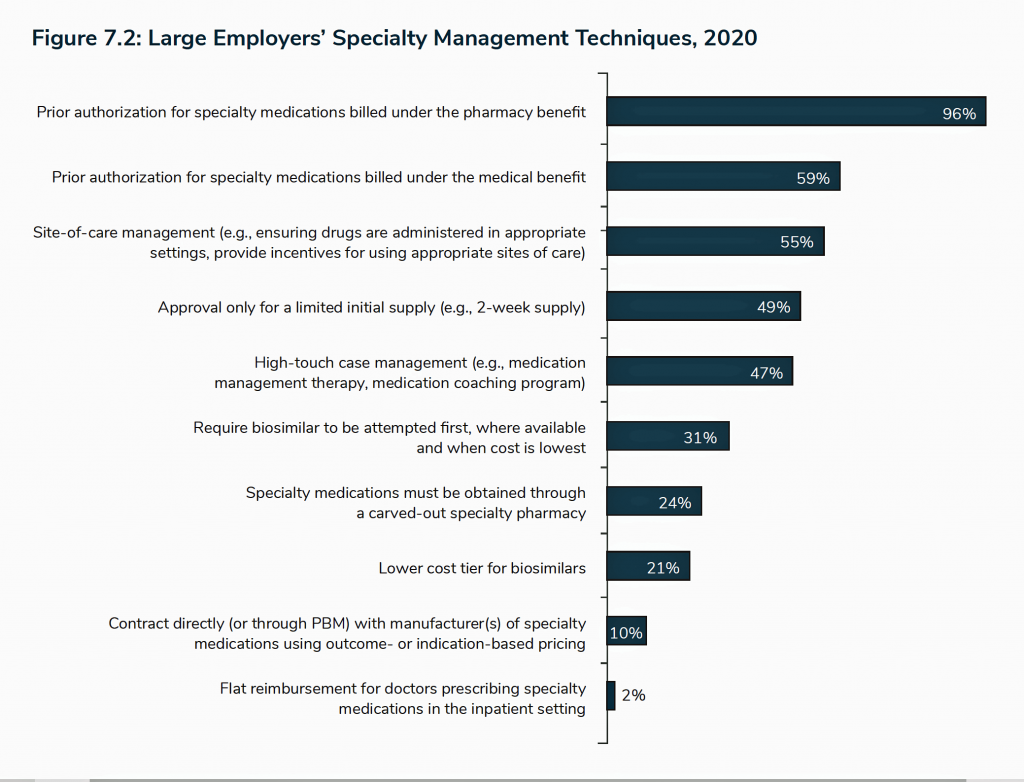

It’s specialty drugs that will be a significant wild-card for companies’ prescription drug spending: prior authorization, a time-tested tactic on the health services side of cost management, is the prevailing method among large companies looking to manage high-cost therapy spending. Virtually all large companies use prior authorization to consider coverage for specialty medicines billed under a worker’s pharmacy benefit.

The last chart details other strategies adopted for managing specialty drug costs, including site-of-care management which establishes protocols for where drugs are administered; limiting the supply of drugs; case management and medication management; and, requiring biosimilars to be used first as step therapy before approving the more expensive specialty therapy.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Prescription drug costs are a front-of-mind, kitchen table issue for Americans in 2019 and looking forward. Across party identification, U.S. health citizens favor government intervention to manage down drug prices, the Kaiser Family Foundation Health Tracking Poll found earlier this year which I discussed here in Health Populi.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Prescription drug costs are a front-of-mind, kitchen table issue for Americans in 2019 and looking forward. Across party identification, U.S. health citizens favor government intervention to manage down drug prices, the Kaiser Family Foundation Health Tracking Poll found earlier this year which I discussed here in Health Populi.

Fully 8 in 10 Americans say the government should be allowed to negotiate lower prices with drug companies for people enrolled in Medicare, shown in the bar chart from the KFF poll. Note, too, that 63% said the government should levy taxes on drug companies whose prices are “too high,” and over half of U.S. adults think the government should end the tax break on advertising spending for drugs.

As I wrote to @Cascadia (Sherry Reynolds) in a Twitter conversation on my first NBGH post discussing the 2020 employer survey, large companies are a political lobby when it comes to health care spending and services. As a major payor, with government and consumers, the largest employers’ operating structures depend on current tax policy regarding how healthcare spending is treated in the tax code. In addition, some industries heavily depend on attracting and retaining employees based on a carefully curated mix of benefits, of which health care in the current environment is a much-desired line item.

The NBGH data, on both health care services and prescription drugs, is useful information to mix into our forecasts on health care reform scenarios for the coming 1-3-5 years. Much now depends on the U.S. macroeconomy — signs of which this week point to a very real possibility of recession and economic downturn. The margins between voters’ demands for single payer versus Medicare4All versus public option/ACA update may become increasingly thin.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for