Data security breaches, access challenges, and privacy leakages plague the current state of Americans’ personal health information (PHI).

HIPAA, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act that was legislated in 1996, isn’t sufficiently robust to deal with the nature of this health information 23 years after that law was first implemented.

HIPAA, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act that was legislated in 1996, isn’t sufficiently robust to deal with the nature of this health information 23 years after that law was first implemented.

That’s not a typo in the title: Ciitizen (spelled with two “i’s”) launched a The Patient Record Scorecard on 14th August. The Scorecard was developed to gauge the progress (and lack thereof) of patient information access afforded by peoples’ health care providers.

What did Ciitizen learn from this process? “The majority of medical record providers are not compliant with the HIPAA Right of Access,” Deven McGraw is quoted on the Ciitizen website. Deven’s observation is made based on Ciitizen’s study into some 3,000 medical record facilities between August 2018 and May 2019.

Deven McGraw is Ciitizen’s Chief Regulatory Officer. [In full transparency, I also consider her a long-time colleague and friend in healthcare. FYI, she was a valuable peer reviewer for the health care privacy chapter in my book, HealthConsuming. Deven was the ideal peer reviewer on patient privacy because she had joined Ciitizen following her tenure as Deputy Director for Health Information Privacy at the Office of Civil Rights, Department of Health and Human Services].

The patient scorecard portal allows us to access and compare information access scores and details by organization, gleaned from Ciitizen’s survey. Health care providers are rated on the basis of a five-star (*) score, where:

* = Non-HIPAA compliant

** = HIPAA compliant requiring substantial intervention

*** = HIPAA compliant with minimal intervention to gain access

**** = HIPAA compliant in a seamless process

***** = HIPAA compliant, patient-focused.

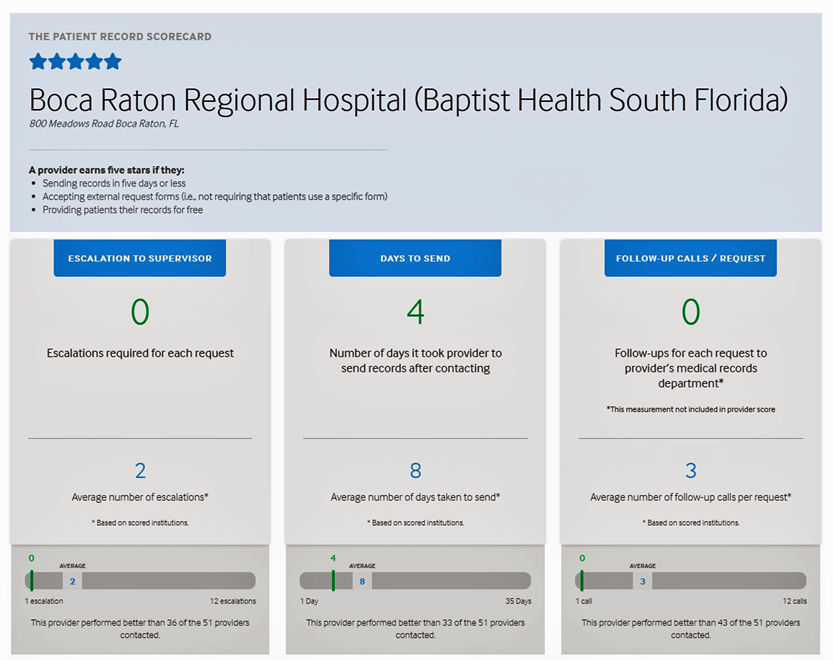

The scorecard website provides details for each of the medical record organizations reviewed. For example, here’s the snapshot of a five-star provider, the Boca Raton Regional Hospital (aka Baptist Health South Florida). [I selected this provider as it was the first provider on the alphabetical list with a five-star review]. Ciitizen’s review of the hospital found no escalations to supervisors were required for patients’ requests for personal information; the requests took 4 days to provide to the patients; and, no follow-up calls were received for the requests.

The scorecard website provides details for each of the medical record organizations reviewed. For example, here’s the snapshot of a five-star provider, the Boca Raton Regional Hospital (aka Baptist Health South Florida). [I selected this provider as it was the first provider on the alphabetical list with a five-star review]. Ciitizen’s review of the hospital found no escalations to supervisors were required for patients’ requests for personal information; the requests took 4 days to provide to the patients; and, no follow-up calls were received for the requests.

In contrast, average escalations would be 2, days to send 8, and follow-up calls 3.

Do visit the scorecard website to see providers with scores ranging from the low of one-star lacking HIPAA compliance 100%, through the stars up to five represented by Boca Raton’s leadership for being patient-centered when it comes to providing health consumers quick and efficient access to their information.

Why is this so important? As Deven asserts in her blog on the patient record scorecard, “I came to Ciitizen in 2017 to help enable patients…to use their HIPAA Right of Access to have their health records at the ready, so they can seek second opinions, determine eligibility for clinical trials, and donate their data for research. With the OCR Right of Access guidance front of mind, I was confident we could help our users gather their health information with little (if any) friction. Boy, was I wrong. Sadly, the guidance seems to have made little difference in helping patients easily exercise their HIPAA Right of Access in gathering records from their medical providers.”

A study published in the October 5, 2018, issue of JAMA Network Open found diverse and disappointing results for patient information access among 83 top-ranked U.S. hospitals based on the “top hospitals” list published by U.S. News & World Report in 2016-17.

The study assessed the type of information patients requested (test results, the entire medical record, etc.), request-receipt processing time, and costs to provide the information, among other measures.

The vertical bar chart here is excerpted from the study and illustrates the mean time to release of a requested record to the patient making the request ranged from under 7 days to as much as over a month. When it came to cost, the federal recommendation is $6.50 for a digital record; one hospital in this study charged as much as $541.50 for a 200-page record.

“Requesting medical records remains a complicated and burdensome process for patients despite policy efforts and regulation to make medical records more readily available to patients,” the authors of the JAMA research conclude.

Ciitizen’s business is to enable patients to gain ready access to their health records — something that’s clearly not so easy to do. And the implications of a patient or caregiver not being able to readily access their data can be dire: consider the bar chart and how you would deal with facing waiting over a week for your data so you could get a second opinion for an initial end-stage cancer diagnosis? This was one motivation of Ciitizen’s founder, Anil Sethi, whose sister succumbed to cancer. We are all shoemakers’ children with no shoes at some time in our life, that is something I-know-I-know.

Deven McGraw offers this counsel the patients, which is all of us: “If you’ve requested a copy of your health record and found getting a copy to be difficult, I have some good news for you regarding your rights. You have plenty of them.”

Health Populi’s Hot Points: There’s a huge irony and challenge I discuss in my book, HealthConsuming: From Health Consumer to Health Citizen. In the chapter of “Privacy and Health Data In-Security” (the one that Deven expertly reviewed), I detail the growing volume, variety and velocity of data each of us generates, daily, that mashed up together can paint a complete picture of our health. These are illustrated in the graphic here, which is a riff on the original concept drawn by Juhan Sonin of the Goinvo design studio.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: There’s a huge irony and challenge I discuss in my book, HealthConsuming: From Health Consumer to Health Citizen. In the chapter of “Privacy and Health Data In-Security” (the one that Deven expertly reviewed), I detail the growing volume, variety and velocity of data each of us generates, daily, that mashed up together can paint a complete picture of our health. These are illustrated in the graphic here, which is a riff on the original concept drawn by Juhan Sonin of the Goinvo design studio.

The irony is that, in the U.S., our medical records are held by folks we need to trust to be good stewards of that very personal information. We can’t readily access it, the Ciitizen and JAMA studies, among many others, have shown.

But there are plenty of data “leakages” of the bits of our digital dust we leave through apps and GPS check-ins and social networking posts that third parties scrape together. Many of these fall outside the purview of HIPAA and other U.S. privacy laws covering children online, genetic information, and agreements we sign with third-party mobile app developers.

Clearly, as the Ciitizen team knows and is working on, the HIPAA regulations need to be enforced and fully realized to both protect U.S. health citizens and enable people to gain access to their much-needed health information held by medical record organizations. That’s the “now” scenario.

Going forward, I argue for a more comprehensive form of privacy protection that recognizes the new world of data shown in Juhan’s concept, the kind of which are fellow health citizens in the EU enjoy through the GDPR. It’s an opt-in, not an opt-out, paradigm, with the right to be “forgotten” if we so choose to be.

When we are diagnosed with a condition, many of us want to share our information with researchers, other peer patients, and third parties based on our own values and goals. That’s our call, or should be.

The privacy chapter in my book concludes with a story about a conversation between Judith Faulkner, CEO of Epic (the health IT company) and Vice President Joe Biden. They’re at a meeting of the Cancer Moonshot in August 2017, and Faulkner asked Biden, “Why do you want your medical records? They’re a thousand pages of which you understand 10.”

To which Biden responded: “None of your business.” That story can be found here in POLITICO.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for