Older people are re-framing their personal images and definitions of aging, from continuing to work past typical retirement age, Skyping and texting with grandchildren, and traveling to destinations well beyond the “snowbird” locales of Florida and Arizona to more active and often charitable/volunteer situations in developing economies.

And so, too, are older folks re-imagining how and where their health care services could be delivered and consumed. Most people over 50 years of age are cautious but open to receiving health care virtually via telehealth platforms, according to the National Poll on Healthy Aging from my alma mater, the University of Michigan.

U-M’s Institute for Healthcare Policy & Innovation conducts the monthly Healthy Aging Poll, sponsored by AARP and Michigan Medicine, the university’s medical school.

This month’s October 2019 study finds a cohort of Boomers and older peers few of whom have actually used telemedicine — only one in seven people over 50 said their providers offered care via telehealth, and only 4% of people had a telehealth visit in the past year.

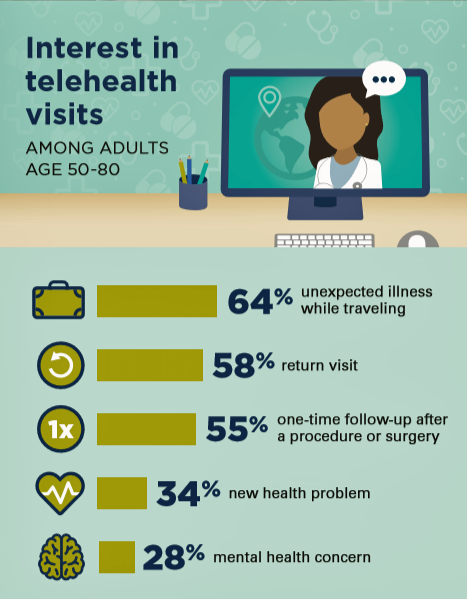

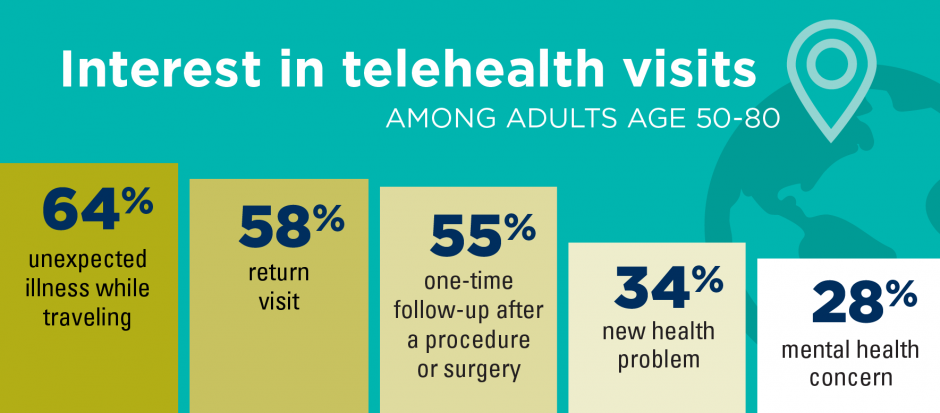

But if they were offered telehealth services, most people over 50 would be interested in care when traveling, for follow-up visits (say, to manage previously-diagnosed chronic conditions like heart disease or diabetes), and after surgeries.

Convenience is the overwhelming advantage of virtual care among older people, with most folks concerned about the quality of the visit citing concerns about feeling “cared for,” (less) time spent with the doctor, and ability to communicate with the doctor.

In addition, worries about privacy, not feeling “connected” to the provider, and concerns about using the technology and one’s ability to see and/or hear the clinician were also cited.

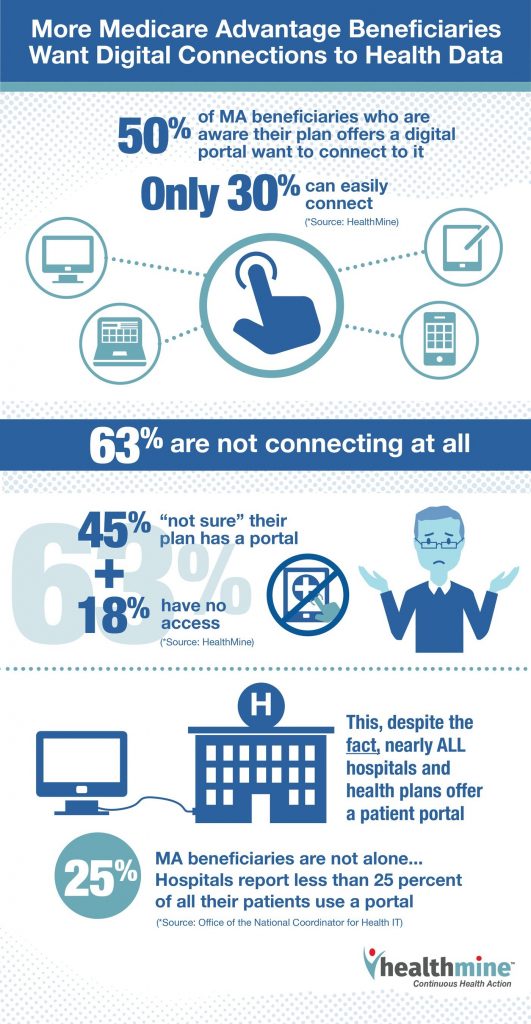

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I recently collaborated with HealthMine on a survey looking into Medicare Advantage members’ views of health and digital technology. In our report, A Call for Care That’s Personal, Accessible and Social, we identify older patients as “digital immigrants,” newer to mobile platforms and digital health tools…but learning how to speak this new ”language” and work-flows of telehealth, mobile health apps, and patient portals.

The U-M Poll bolsters this persona of older people keen to access health in convenient, accessible ways — especially when traveling, going to follow-up visits with clinicians, and following up after a surgical procedure.

We’re in the Field of Dreams moment in telehealth, especially for older people. There’s a chasm and lag between the supply side among providers vis-a-vis the demand side of consumers and, specifically, older patients. Clinicians and health systems have begun to offer and scale up telehealth programs now that these can be coded and reimbursed — together factors that were the biggest obstacles to telehealth provision in the community.

On the demand-patient side, and especially for older people, there’s clearly a lack of awareness of this care platform being available when it is. The HealthMine study found folks largely unaware of patient portals, for example.

It’s not enough to build/offer digital health tech to patients. Putting on our design-thinking hats, we must work through patients’ work- and life-flows for health care in a 360-degree way to understand how people actually live, prioritize health care in their lives (or not), schedule appointments, ask for and take advice, and follow up with self-care or referred visits.

This is a health behavior-and-education approach requiring team players in the larger health/care ecosystem. Retail health channels, whether via Best Buy, CVS/health and Walgreens, or direct-to-consumer services we see via GoodRx and Hims/Hers, for example, are emerging to fill this gap on the supply side of this equation.

But remember that the trusted relationship — for “now” — remains between the patient and the doctor, nurse and pharmacist. There’s a window of opportunity and near-term time for providers to bridge this gap building on and leveraging that trust-relationship.

As a proud Big Ten alum, I'm thrilled to be invited to

As a proud Big Ten alum, I'm thrilled to be invited to  I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming CES 2025 Innovation Awards in the category of digital health and connected fitness. So grateful to be part of this annual effort to identify the best in consumer-facing health solutions for self-care, condition management, and family well-being. Thank you, CTA!

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming CES 2025 Innovation Awards in the category of digital health and connected fitness. So grateful to be part of this annual effort to identify the best in consumer-facing health solutions for self-care, condition management, and family well-being. Thank you, CTA! For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,