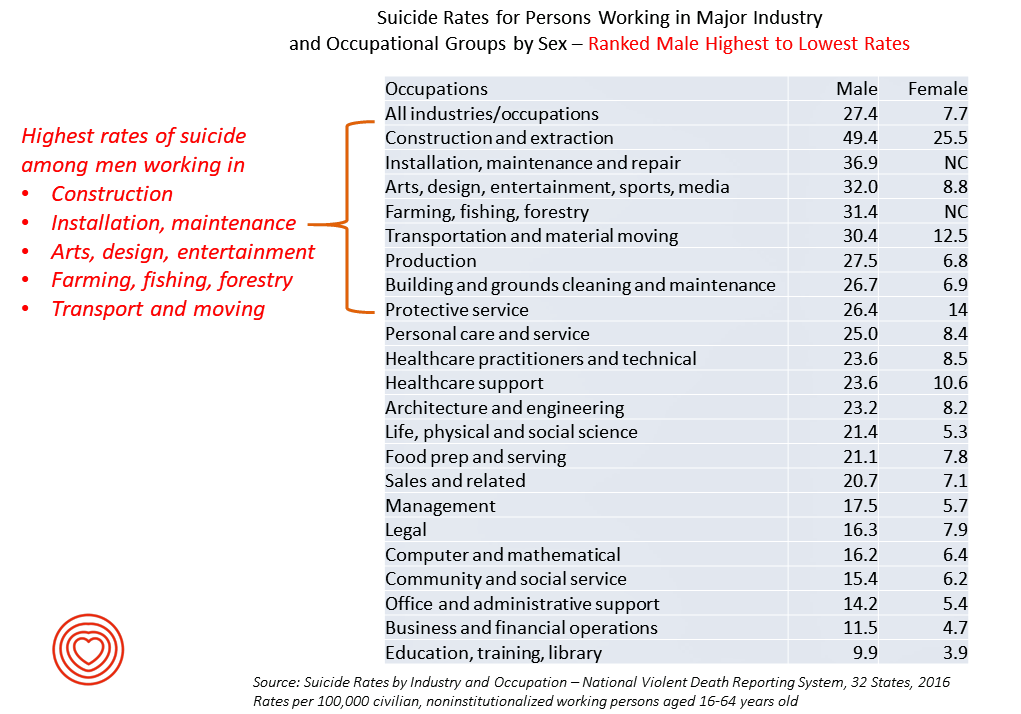

The rate of suicide in the U.S. rose from 12.9 per 100,000 population to 18.0 between 2000 and 2017, a 40% increase. Those workers most at-risk for suiciding were men working in construction and mining, maintenance, arts/design/entertainment/sports/media, farming and fishing, and transportation.

The rate of suicide in the U.S. rose from 12.9 per 100,000 population to 18.0 between 2000 and 2017, a 40% increase. Those workers most at-risk for suiciding were men working in construction and mining, maintenance, arts/design/entertainment/sports/media, farming and fishing, and transportation.

For women, working in construction and mining, protective service, transportation, healthcare (support and practice), the arts and entertainment, and personal care put them at higher risk of suicide.

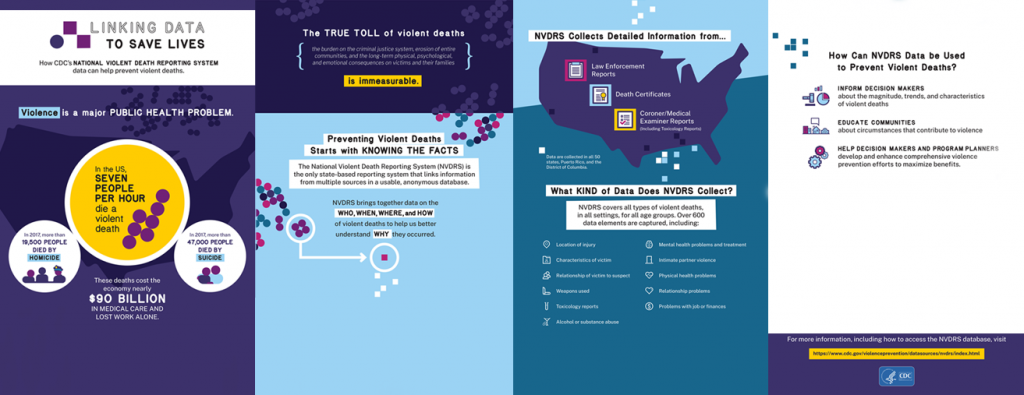

The latest report from the CDC on Suicide Rates by Industry and Occupation provides a current analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System which collects data from 32 states, this data set from 2016.

The reporting system is one of the world’s largest databases on deaths due to violent causes. The program collects information from death certificates, coroner/medical examiner reports, law enforcement reports, and toxicology reports into an anonymous database. The data can be quite granular with information on mental health diagnoses and treatments, toxicology tests, and stressors such as health problems, relationship-, financial- or work-related challenges.

The reporting system is one of the world’s largest databases on deaths due to violent causes. The program collects information from death certificates, coroner/medical examiner reports, law enforcement reports, and toxicology reports into an anonymous database. The data can be quite granular with information on mental health diagnoses and treatments, toxicology tests, and stressors such as health problems, relationship-, financial- or work-related challenges.

The national average suicide rate for men in 2016 was 27.4 per 100,000 males; for women, the suicide rate was 7.7 per 100,000 females. Thus, men were nearly 4 times more likely to commit suicide in 2016 than women were.

Underneath that sobering median statistic is the undeniable fact that more people in blue collar jobs are more at-risk of committing suicide than people in service or professional careers. For example, for men, the lowest rates of suicide were found among workers in education, business and finance, office and administration, social service, computers, legal, management and sales.

For women, the least risky occupations were education, business, life/physical/social science, office and admin, management, community and social service, computer and math work.

CDC’s bottom line recommendation is that, “All industries and occupations can benefit from a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention,” including strategies such as,

- Promoting help-seeking

- Integrating workplace safety and health and wellness programs to advance the overall well-being of workers

- Referring workers to financial and other helping services

- Facilitating time off and benefits to cover supportive services

- Training personnel to detect and appropriate respond to suicide risk

- Creating opportunities for employee social connectedness

- Reducing access to lethal means among persons at risk

- Creating a crisis response plan sensitive to the needs of coworkers, friends, family, and others who might themselves be at risk.

Finally, strengthening economic supports, access and delivery of care, teaching coping and problem-solving skills were among CDC’s community-based recommendations.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: One of my jobs is forecasting likely futures, and one of the likelihoods will be more jobs lost to automation, robotics, and mobility. This was a big theme at CES 2020 this year, and I explored that content to add into my tea-leaf-reading.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: One of my jobs is forecasting likely futures, and one of the likelihoods will be more jobs lost to automation, robotics, and mobility. This was a big theme at CES 2020 this year, and I explored that content to add into my tea-leaf-reading.

We’ve seen the loss of jobs in the mining and extraction industries, manufacturing, and other so-called blue-collar jobs in America over the past two generations. The pace of this change will quicken as AI, machine learning, and autonomous cars come to make our lives (potentially) easier, more informed streamlined in this current generation and ongoing.

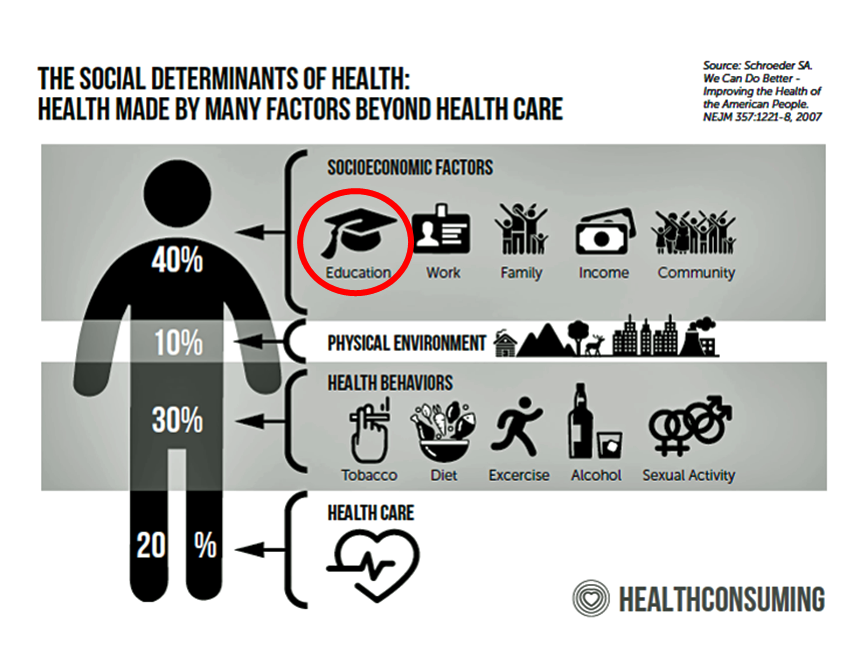

As jobs are lost to these innovations, the role of education is so central to mitigating the negative future scenarios, and education on many levels — for new job training and up-skilling, for mental health and health care, for financial health, and so on.

The great irony in the data is also the opportunity: that the lowest-risk category for suicide among all career paths is….education. Among men in education, the suicide rate was 9.9 per 100,000 (compared with male risk of 27.4 across all jobs). For women educators, the suicide risk was 3.9 per 100,000 compared with 7.7 across all women working.

The great irony in the data is also the opportunity: that the lowest-risk category for suicide among all career paths is….education. Among men in education, the suicide rate was 9.9 per 100,000 (compared with male risk of 27.4 across all jobs). For women educators, the suicide risk was 3.9 per 100,000 compared with 7.7 across all women working.

The opportunity is to continue to educate the educators, reward them for the great ROI they can co-create with their students — whether kids, adults, workers, older people seeking connections, all of us. We know from Deaton and Case’s research into Deaths of Despair that the lack of education is a high risk for dying from accidents, suicide and drug overdose. The CDC report bolsters this, compelling us to re-invest and commit to education as the macro social determinant of health it is.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for