“Covid-19 exposes America’s racial health gap,” asserts The Economist, the weekly news magazine based in London, UK, in an advanced essay dated 11 April 2020. The subtitle of the piece: “African-Americans appear more vulnerable to the virus.”

The phrase, “your ZIP code is more important than your genetic code” has become the common mantra for public health people communicating the concept of the social determinants of health: those factors outside of medical services that shape peoples’ overall health and well-being.

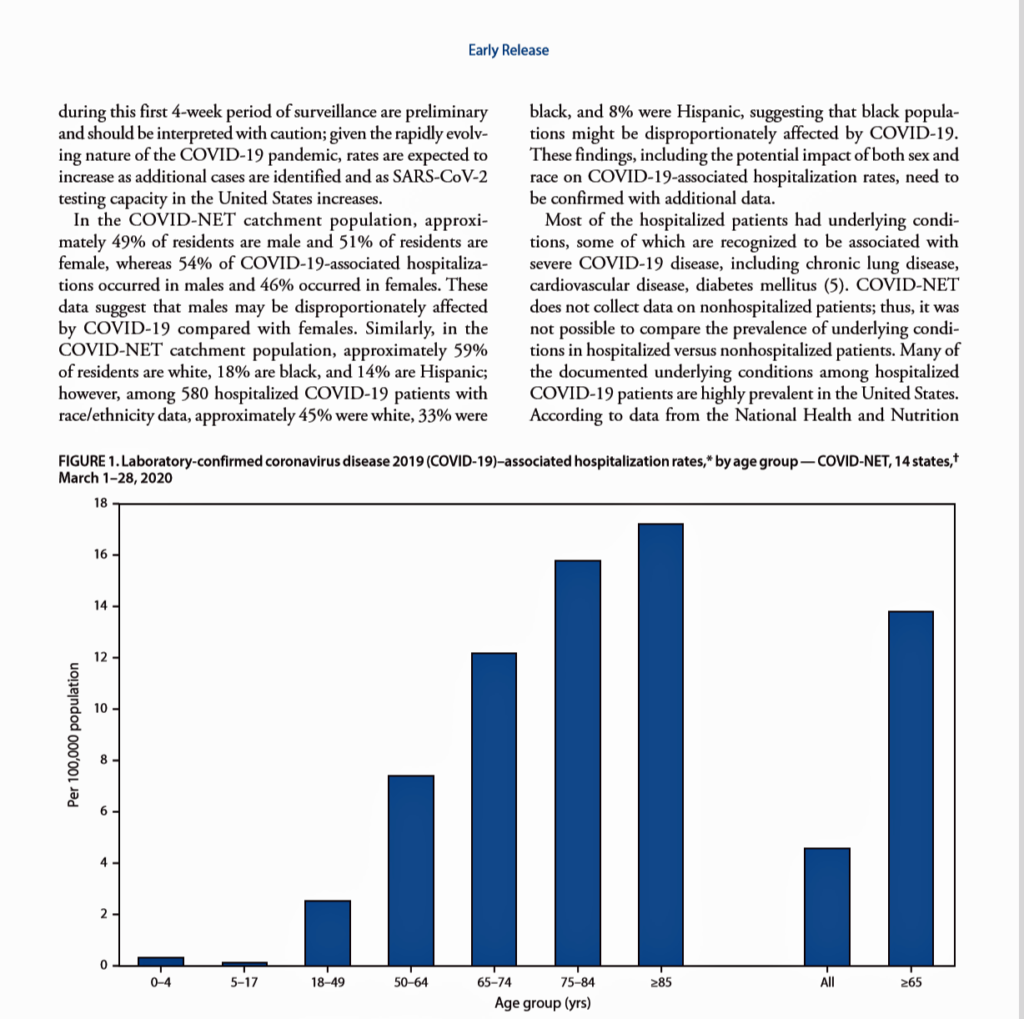

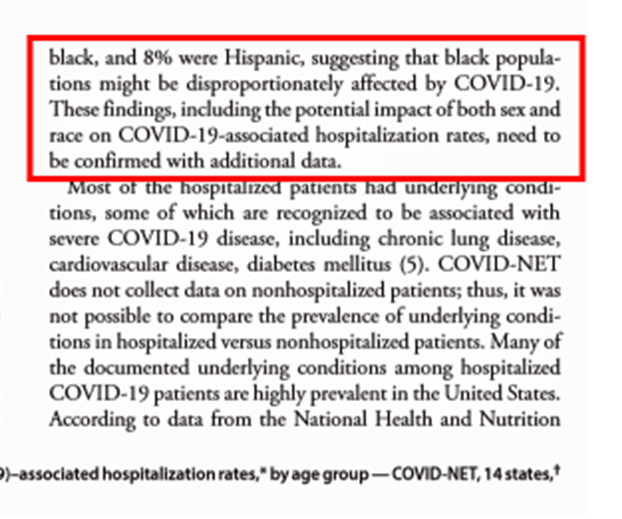

Two days ago, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) published data that showed African-Americans were dying from complications of the coronavirus (C19) at a much higher rate than white Americans.

Two days ago, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) published data that showed African-Americans were dying from complications of the coronavirus (C19) at a much higher rate than white Americans.

State-level data revealed that in Louisiana, black people comprised 70% of COVID-19 deaths even though they are only 32% of the state’s population.

In Michigan, African-Americans made up 40% of deaths from C19, but only 15% of the state’s residents.

And, in Illinois, black people make up 14% of the state’s population but represented 40% of deaths from the coronavirus.

The mass media and the President of the United States grabbed onto this data point in a collective way, everyone on broadcast TV and newsprint calling this out.

During the White House Coronavirus Task Force briefing the day of the published CDC report, President Trump said: “We’re seeing tremendous evidence that African-Americans are affected at a far greater percentage number than other citizens of our country. But why is it that the African American community is so much, numerous times more than everybody else? We want to find the reason to it.”

Newspapers reported on the CDC statistic:

The New York Times wrote, “Rate of Deaths, Illness Among Black Residents Alarms Cities.”

The Los Angeles Times noted for its town, “L.A. releases first racial breakdown of coronavirus fatalities; blacks have higher death rate.”

Fox45 News in Baltimore reported, “COVID-19: African-Americans impacted the most in Maryland.”

And, Alabama’s ABC News channel noted, “COVID-19 killing more African Americans in Alabama, data shows.”

Dr. Anthony Fauci, American’s favorite COVID-19 fact-checker, further explained in the White House Briefing, “We’re very concerned about that. It’s very sad. It’s nothing we can do about it right now except to try and give them the best possible care to avoid those complications.”

Health Popuil’s Hot Points: “There’s a 15-year difference in the life expectancy between the richest and poorest Americans. That gap is largely attributable to geography. Place matters for a person’s health,” I wrote in Chapter 7 of my book, HealthConsuming: From Health Consumer to Health Citizen.”

Health Popuil’s Hot Points: “There’s a 15-year difference in the life expectancy between the richest and poorest Americans. That gap is largely attributable to geography. Place matters for a person’s health,” I wrote in Chapter 7 of my book, HealthConsuming: From Health Consumer to Health Citizen.”

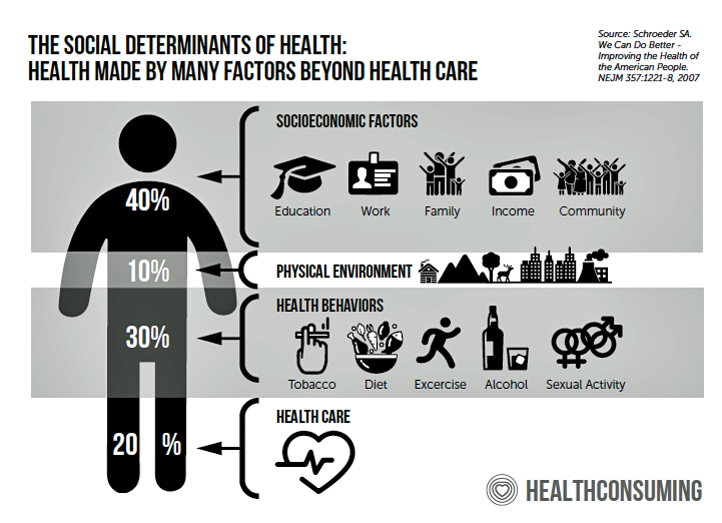

The social determinants of health are conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live and age. This chart, from the book, illustrates these as socioeconomic factors like education and income, our physical environment (think: clean water in Flint or Newark, clean air in Los Angeles), and our health behaviors like smoking, nutrition and how much alcohol we consume.

“There are places where you pay a price in the loss of life because of your address,” Dr. Anthony Iton wrote back in 2008 when he was health director of Alameda County, California.

Dr. Iton may have been the first person to coin the phrase about our ZIP codes pre-determining our health outcomes.

So this week’s finding by the CDC of that tragic statistic — that the coronavirus is killing more black people than white people, per capita, in America — was very sad to me. But not a surprise.

The health disparities and health inequities in the United States among people of color stem from social determinants and decades of institutional barriers like racism — which translates into people of color often not receiving modern standards of care and clinical protocols, and higher risks for chronic conditions like diabetes, heart disease and obesity.

As African-American patients have been admitted to U.S. hospital emergency rooms with symptoms of COVID-19, a greater number of these patients per capita haven’t been discharged from hospitals.

They’ve passed away.

In this moment, doctors and nurses and respiratory therapists, and peer clinicians on their teams, are fighting hard to save all C19 patients on COVID wards and in ICUs, in field hospitals and nursing homes. These heroes are attending to the immediate crisis of caring for patients fighting C19, some still needing sufficient personal protected equipment even these many weeks in this so-called “wartime” battle.

But we must be capable, in the U.S., of holding more than one thought in our minds as the Great Coronavirus Battle continues for many weeks, and months, to come. That second idea is what comes after this specific pandemic in terms of the U.S. health care system.

As The Economist clearly observed, correctly, the coronavirus has exposed America’s health gap. The gifts of going through crises is that we can learn from them and inform decisions to make things better.

In this case, it’s our opportunity to re-form, re-inform, and re-imagine the U.S. health care system and how scarce resources get allocated to medical care and social care. The U.S. has a thinner and poorly distributed primary care backbone compared with other wealthy countries who spend far less and achieve far greater health outcomes than American health citizens enjoy for that hefty medical spend.

For the latter social care line item, we “can” bake health into broader public policies of education, agriculture for food and nutrition security, infrastructure and environmental investments that help people be healthy and “make health” at home and in our communities. “Can” doesn’t mean we will — it’s our opportunity to make that choice as a nation of health citizens, and not merely health consumers.

One pillar of “health citizenship” is for a nation to ensure that all residents have access to health care as a civil right. Another is privacy protection.

Those are the rights-side of health citizenship. But there are responsibilities, too — to care about our neighbors, as we are doing right now by #StayingHome and covering our faces with DIY masks en masse. Another responsibility is voting — one person, one vote, our right and responsibility that, come November, is part of our overall health citizenship in taking back our health care system for the benefit all Americans — including our doctors, nurses, allied health professionals, and our selves.

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider

I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider  Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for