The Coronavirus has impacted every aspect of human life: first, the direct biological impact of COVID-19 on people, as of today the cause of over 63,000 deaths in the U.S. along with unquantifiable morbidity among millions of Americans who are surviving the virus and the toll on family caregivers.

Beyond the direct physical impact of the virus, social and emotional health impacts are emerging now due to physical distancing, mandates to #StayHome, and telecommuting to jobs when possible. Mental health impacts will persist as a pandemic after the Coronavirus pandemic, I’ve previously detailed here in Health Populi.

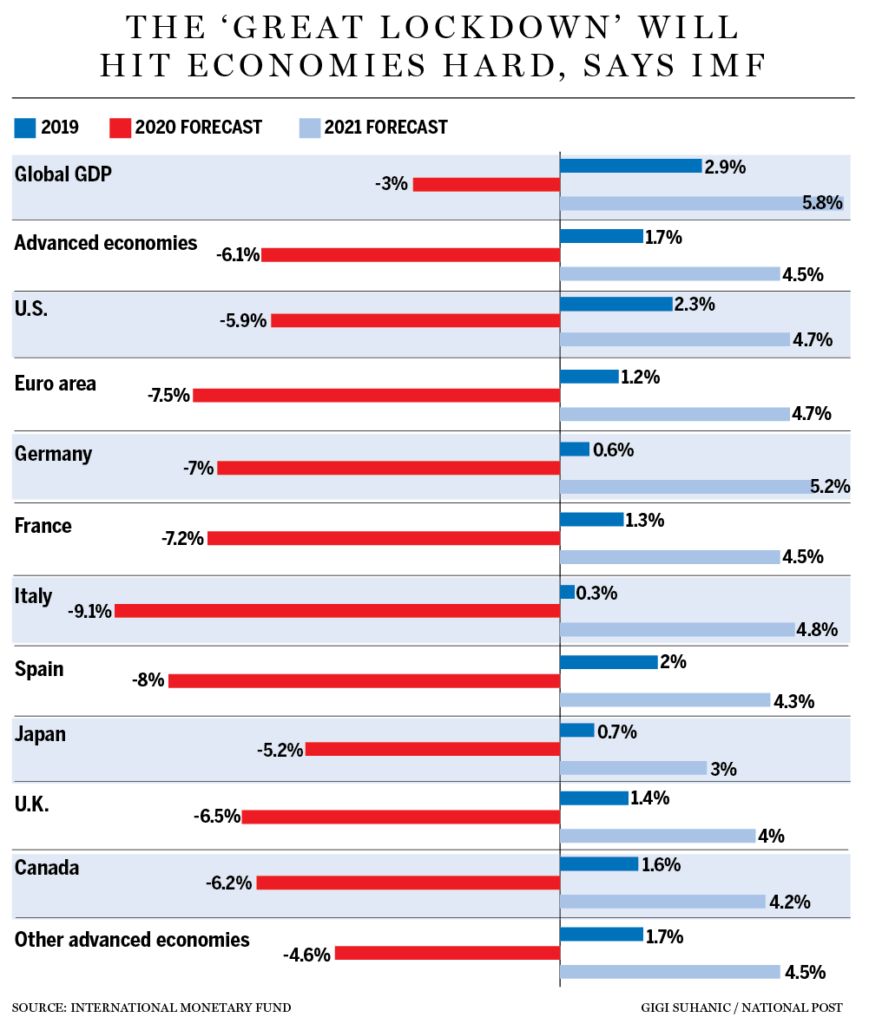

On a global basis, COVID-19 has also forced a global economic shock in The Great Lockdown, as the International Monetary Fund coined the current state of negative growth around the world. The IMF forecasted that the U.S. economy would decline in 2020 by 5.9%, shown in the bar chart.

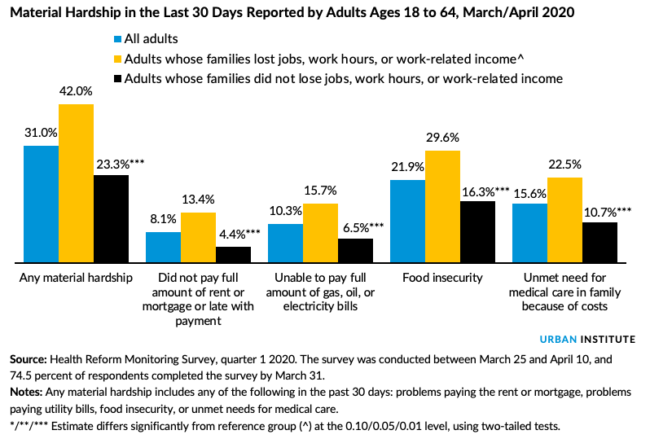

On a household level, 30 million jobs were lost based on unemployment claims filed between mid-March and April 25, COVID-19 is exacting material hardships, according to an Urban Institute report on families’ abilities to afford basic needs during the pandemic.

By April 10th, four in ten working people age 18 to 64 had felt one or more of these impacts in the past 30 days; those hardships included food security, medical care, ability to pay for energy (gas, oil or electric bills), or pay for housing (rent or mortgage).

These impacts, of course, have more severely hurt people whose families lost jobs, had work hours cutback, or lost work-related income.

Among the hardships, food security was the most-felt, by one in three working adults.

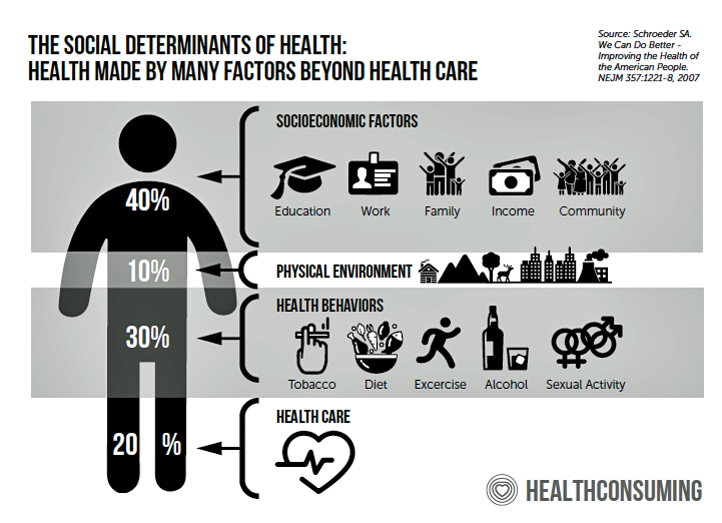

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The material hardships quantified by the Urban Institute are basic needs that make up social determinants of health. Food and housing have been recognized as core factors underpinning health and well-being, recently embraced by health care providers and health plans.

There’s a growing list of programs provided by health system stakeholders, as well as private sector companies, to address food and housing security. Kaiser Permanente and Geisinger have been providing access to produce and healthy food for years, and last year Microsoft began to invest in housing programs.

There’s a growing list of programs provided by health system stakeholders, as well as private sector companies, to address food and housing security. Kaiser Permanente and Geisinger have been providing access to produce and healthy food for years, and last year Microsoft began to invest in housing programs.

There’s a point of view (with which I concur) that social determinants of health are really part of public health and a larger concept of health citizenship I called out in USA Today on February 7, 2020.

Brookings Institution’s analysis of the Urban Institute data notes that food insecurity disproportionately affects low-income Hispanic and African-American people, a statistic found both in Urban’s study as well as borne out in the higher impact of COVID-19 deaths in communities of color.

“How can we keep families fed?” Brookings asks. The answer lies in national, scaled federal nutrition programs like SNAP benefits, waivers for schools and community organizations to provide food, broader implementation of Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT), and blocking rules that would restrict access to SNAP benefits such as reinstating work requirements especially while unemployment is high.

The top line of the SDoH graphic is socioeconomic factors, which have to do with education and jobs — which in the U.S., tie to health insurance coverage. With the loss of 30 million jobs also comes loss of health insurance for millions of those families dependent on the workers losing employment. COVID-19 reveals many cracks in the current U.S. health care system: in the Urban Institute study, we see food security, housing, and health care social determinants eroding in the pandemic era. Addressing the larger role of health citizens, engaging in health and the right to vote, coupled with addressing income inequality and living wages, is one of the “gifts” that the pandemic gives us as we re-build the public health infrastructure to be better positioned for future pandemics in a more civil society.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for