“Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and the most inhuman because it often results in physical death,” Martin Luther King, Jr., asserted at the second meeting of the Medical Committee for Human Rights in Chicago on March 25, 1966.

“Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and the most inhuman because it often results in physical death,” Martin Luther King, Jr., asserted at the second meeting of the Medical Committee for Human Rights in Chicago on March 25, 1966.

This quote has been shortened over the five+ decades since Dr. King told this truth, to the short-hand,

“Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.”

Professor Charlene Galarneau recently enlightened me on Dr. King’s original statement in her seminal essay, “Getting King’s Words Right.” Among her many roles, Dr. Galarneau teaches at Harvard Medical School’s Center for Bioethics.

There are 3 major differences in the long-hand versus the short-hand of Dr. King’s observation:

There are 3 major differences in the long-hand versus the short-hand of Dr. King’s observation:

- Health is broader than “health care;”

- “Inhuman” isn’t the same thing as “inhumane;” and,

- “Human lives end because of this injustice,” Dr. Galarneau underscores.

It’s Juneteenth 2020 in the United States of America, and we find ourselves at a moment of convergence of these three issues.

First, what we in public health circles have been coining the social determinants of health have revealed themselves to be the “moral determinants of health.” This is the title of a new Viewpoint by Dr. Donald Berwick, published in JAMA on 12th June 2020. Dr. Berwick enumerates the circumstances outside of healthcare can nurture or impair health, listing Michael Marmot’s conditions of birth and early childhood, education, work, the social circumstances of elders, community resilience factors (like transportation, housing, security, and community self-efficacy), and ultimately “fairness,” addressing income inequality.

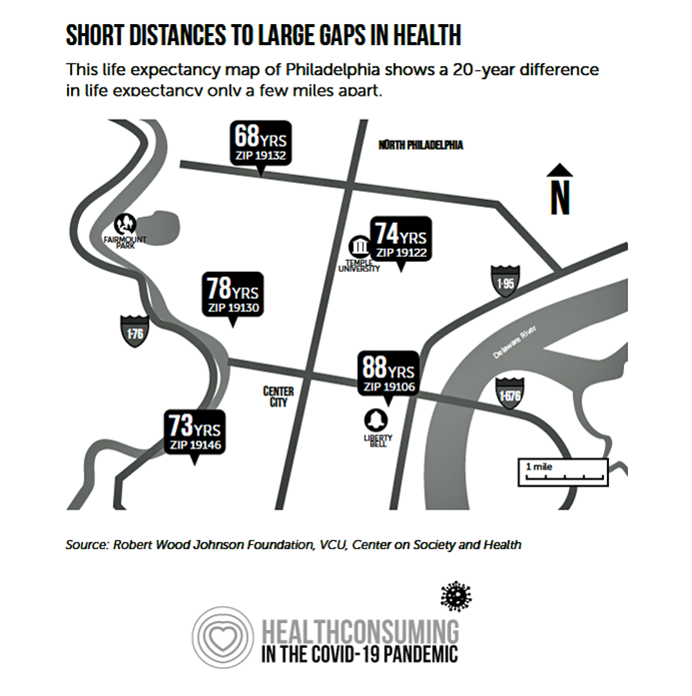

For an individual person, these factors generally occur in groups, which is why the phrase, “your ZIP code is a better predictor of health than your genetic code” has mainstreamed. The map shown here illustrates a portion of Philadelphia, my town, pointing to the stark life expectancy differences between 19106, the Society Hill neighborhood by the Liberty Bell in Center City, where people can live to 88 years on average; and, the ZIP code 19132 in North Philadelphia, where life span can be cut down to 68 years.

This 20-year difference happens within just a few miles of two people living in the City of Brotherly Love.

Why “moral” determinants of health? Because, Dr. Berwick explains, “The angry despairing victims of inequity, and their supporters, marching in the streets of the US despair in part because they and their parents and their grandparents and generations before have been waiting far too long. They find no moral law in evidence, no social contract bilaterally intact. They do not believe in promises of change, because for too long people remain hungry and homeless, with the doors of justice so long closed.”

Ultimately, he is hopeful: “Improving the social determinants of health will be brought at last to a boil only by the heat of the moral determinants of health.”

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I grew up in suburban Detroit. In 1967, the city erupted in what was called “riots.” The city “billowed in smoke,” one news report described, the photo here one of many taken in the moment of “boil-over,” to take a phrase from Dr. Berwick’s last sentence.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I grew up in suburban Detroit. In 1967, the city erupted in what was called “riots.” The city “billowed in smoke,” one news report described, the photo here one of many taken in the moment of “boil-over,” to take a phrase from Dr. Berwick’s last sentence.

I was a little girl, and my father made sure his children knew what happened and why. He was a Kennedy-Humphrey-Johnson Democrat, committed to the growing civil rights movement. Our dinner table conversations were as much about politics of the time as what we learned at school on the day, or what we were listening to on the record player. I have two older sisters who played 45s: the Billboard Hot 100 singles that summer included Aretha Franklin’s Respect, Sam & Dave’s Soul Man, and Ain’t No Mountain High Enough by Marvin and Tammi (yes, we lived in Motown and danced to Motown). But at the same time, so-called protest music like For What It’s Worth from Buffalo Springfield, San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair) by Scott McKenzie, and Jefferson Airplane’s White Rabbit were also in the Top 100 that year as we approached the full-protest-boil of 1968 in Chicago, Paris, and around the world.

As the Detroit historic analysis describes (linked above), sympathetic to my Dad’s viewpoint, “The events in late July were an outgrowth of years of protest. To use the contested language of the 1960s, black Detroiters engaged in an uprising against a racially unequal status quo, a rebellion against brutal police and exploitative shopkeepers.”

On Juneteenth 2020, there are people coming together in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, model of, “direct action and creative nonviolence to raise the conscience of the nation.” In this moment, which feels more like a movement, people are younger and older, black and white and brown, native and immigrant, richer and poorer, out in the streets and online from coast to coast, in large cities and small towns.

On Juneteenth 2020, there are people coming together in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, model of, “direct action and creative nonviolence to raise the conscience of the nation.” In this moment, which feels more like a movement, people are younger and older, black and white and brown, native and immigrant, richer and poorer, out in the streets and online from coast to coast, in large cities and small towns.

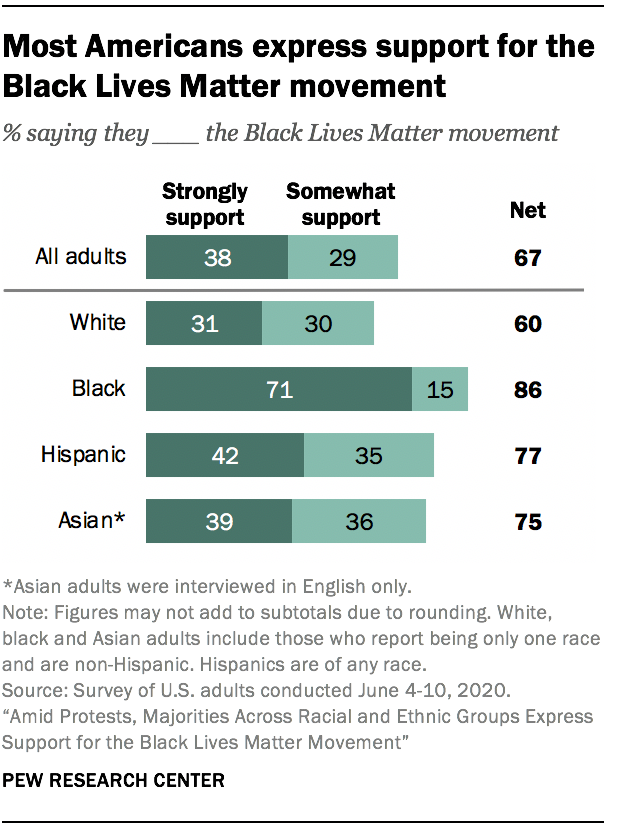

It wouldn’t be the Health Populi blog if I didn’t gift you with a data point and insight from it. Amid the protests following the murder of George Floyd, the Pew Research Center polled U.S. adults and on 12th June 2020 published the findings: majorities across racial and ethnic groups expressed support for the #BlackLivesMatter movement, this bar chart shows us.

On this Juneteenth, I’m encouraged by my fellow Americans, and I know my father would be, as well.

On this Juneteenth, I’m encouraged by my fellow Americans, and I know my father would be, as well.

I leave you with a few lines from another Billboard Top 100 hit from 1967: All You Need Is Love from The Beatles:

Nothing you can sing that can’t be sung

Nothing you can say, but you can learn how to play the game

It’s easy

Nothing you can make that can’t be made

No one you can save that can’t be saved

Nothing you can do, but you can learn how to be you in time

It’s easy

All you need is love

All you need is love, love

Love is all you need

Nothing you can see that isn’t shown

There’s nowhere you can be that isn’t where you’re meant to be

It’s easy

All you need is love

All you need is love, love

Love is all you need…

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider

I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider  Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for