In terms of income, U.S. households entered 2020 in the best financial shape they’d been in years, based on new Census data released earlier this week.

However, the U.S. Census Bureau found that the level of health insurance enrollment fell by 1 million people in 2019, with about 30 million Americans not covered by health insurance.

In fact, the number of uninsured Americans rose by 2 million people in 2018, and by 1.9 million people in 2017.

The coronavirus pandemic has only exacerbated the erosion of the health insured population.

What havoc a pandemic can do to minds, bodies, souls, and wallets. By September 2020, about 36 million people in the U.S. lacked health insurance.

What havoc a pandemic can do to minds, bodies, souls, and wallets. By September 2020, about 36 million people in the U.S. lacked health insurance.

Losing health insurance in the pandemic: a financial toxic side effect. Nearly 7 million Americans lost health coverage due to COVID-19, a national survey from Civis Analytics found, in The State of Health Insurance in COVID-19 America.

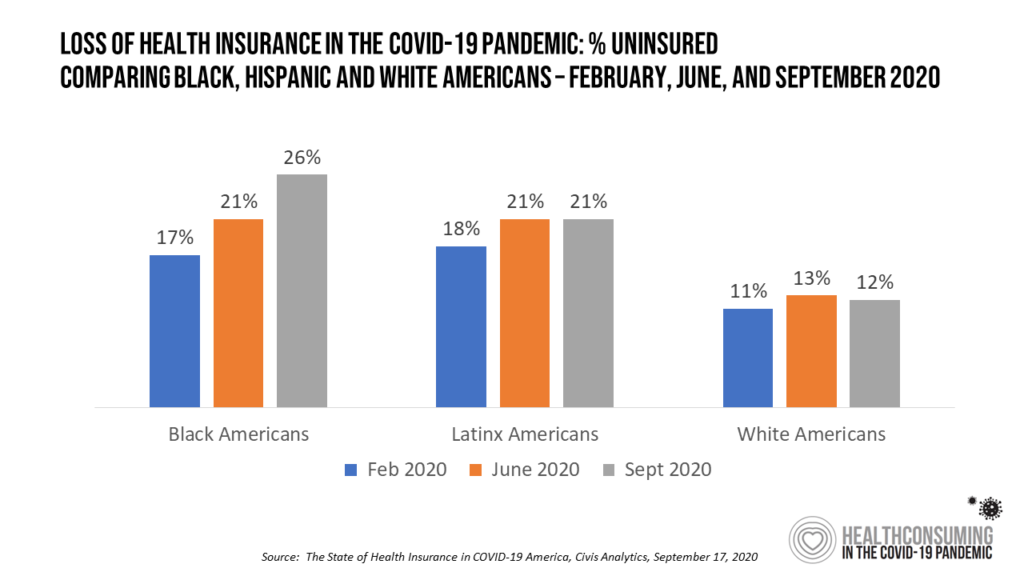

Civis Analytics polled 13,000 U.S. adults in February, June, and September 2020 to gauge peoples’ perspectives on health insurance, knowledge about purchasing health plans, and intent to purchase health insurance if lost during the pandemic.

Gil Bashe, Managing Partner Global Health at Finn Partners, organized a diverse group of industry stakeholders including me to discuss the implications of this timely and impactful study. Our Zoom-based conversation is being held today at noon Eastern time.

Only in America is health insurance tied to the workplace and our jobs. So only in America in the coronavirus pandemic have millions of people lost their health security just when folks would be most needful of access to health care services: during a public health crisis.

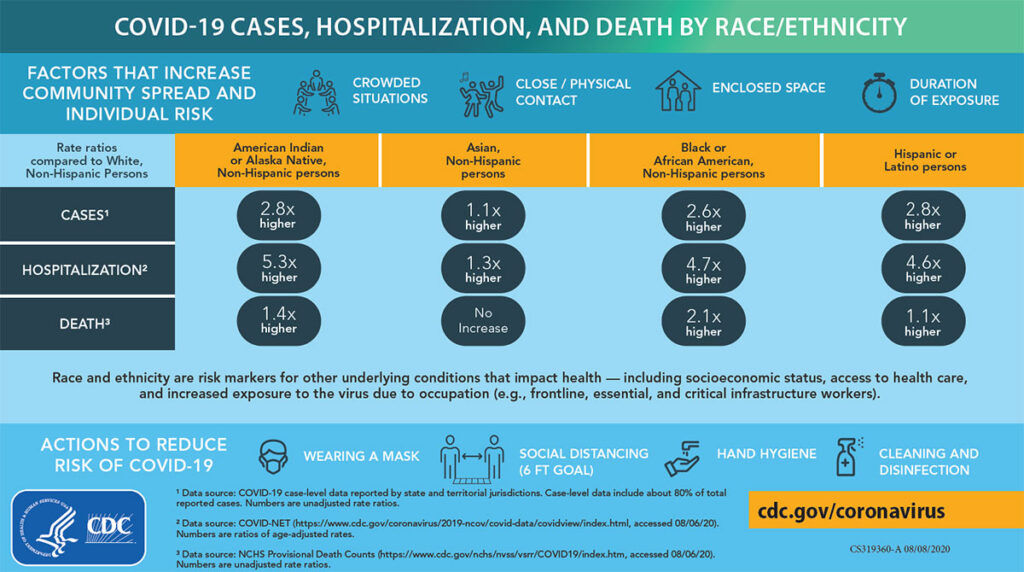

Race matters for health insurance in America. Just weeks into the COVID-19 pandemic, cracks in the U.S. health system in terms of access to medical care and differences in mortality rates emerged. In particular, while roughly equal percentages of White and Black health citizens knew people who had contracted the coronavirus, twice as many Black people in the U.S. knew someone who died from COVID-19.

The loss of health insurance hit communities of color harder than among White Americans. In the Civis Analytics study, one-in-four Black Americans (26%) was uninsured by September 2020, up from 17% in February. In contrast, 12% of White Americans were uninsured in September 2020, just one percentage point higher than in February.

The loss of health insurance hit communities of color harder than among White Americans. In the Civis Analytics study, one-in-four Black Americans (26%) was uninsured by September 2020, up from 17% in February. In contrast, 12% of White Americans were uninsured in September 2020, just one percentage point higher than in February.

Civis Analytics’ finding that Black and Latinx Americans in the U.S. were disproportionately at-risk of losing health insurance builds on other studies conducted in the context of COVID-19’s financial side effects on communities of color. Early in the pandemic, a team of physicians estimated that 18 million U.S. adults at increased risk of severe COVID-19 were inadequately insured and at-risk of delay in seeking care because of cost concerns. This at-risk population was more likely to be Black, earning low-incomes, or living in rural areas. In addition, people living in states that failed to expand Medicaid as part of the Affordable Care Act provisions were also at greater risk of inadequate coverage.

The CDC addressed the issue of social determinants of health disproportionately impacting people of color in July, noting that people from racial and ethnic minority groups were more likely to be uninsured than non-Hispanic Whites. Furthermore, some people in racial minority groups distrust the government and health care systems responsible for inequities in treatment, a sad legacy of the systemic racism in U.S. health care represented by, for example, the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the African American Male” and the treatment of Henrietta Lacks.

The CDC addressed the issue of social determinants of health disproportionately impacting people of color in July, noting that people from racial and ethnic minority groups were more likely to be uninsured than non-Hispanic Whites. Furthermore, some people in racial minority groups distrust the government and health care systems responsible for inequities in treatment, a sad legacy of the systemic racism in U.S. health care represented by, for example, the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the African American Male” and the treatment of Henrietta Lacks.

Civis Analytics’ survey results also comport with other research on health insurance impacts in the pandemic from Avalere, The Commonwealth Fund, the Kaiser Family Foundation, and the Gallup Poll, among others.

Onward, health citizens. In 2003, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published the book, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care.

This was nearly twenty years ago, when the IOM reviewed a large body of research to find that,

This was nearly twenty years ago, when the IOM reviewed a large body of research to find that,

“Racial and ethnic minorities experience a lower quality of health services and are less likely to receive even routine medical procedures than are White Americans. Relative to Whites, African Americans — and in some cases, Hispanics — are less likely to receive appropriate cardiac medication or to undergo coronary artery bypass surgery, are less likely to receive hemodialysis and kidney transplantation, and are likely to receive a lower quality of basic clinical services such as intensive care…These differences are associated with greater mortality among African-American patients.”

I highly recommend you visit the link for Unequal Treatment above to review at least the Executive Summary, which includes this top-line recommendation so relevant all these years later:

Recommendation 2–1: Increase awareness of racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare among the general public and key stakeholders.

Underneath that recommendation is this explanation:

“It is important to note that racial and ethnic disparities are found in many sectors of American life. African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, and Pacific Islanders, and some Asian-American subgroups are disproportionately represented in the lower socioeconomic ranks, in lower quality schools, and in poorer-paying jobs. These disparities can be traced to many factors, including historic patterns of legalized segregation and discrimination.”

With the Civis Analytics study, we uncover a data point in 2020 that the IOM would incorporate into what Hollywood scriptwriters might title, “Unequal Treatment — The Sequel.” Sadly, we’re not living in a sequel: the continued health disparities and inequities that continue to plague American health care are a persistent reminder of systemic racism the nation must cure, making Unequal Treatment not so much a “Part 2” but a continuation of the original plotline.

The Civis Analytics data indeed increases our awareness, consistent with IOM’s Recommendation 2–1.

The remedy is, surely, to expand health care access to quality health care to all people in America. But to get to the root of the root problem, we must also attend to embedding public policies with health for insurance (say, to guarantee pre-existing conditions and ban community rating) along with attending to those social determinants of health that underpin our overall well-being in areas that the health care system can’t address on its own.

The remedy is, surely, to expand health care access to quality health care to all people in America. But to get to the root of the root problem, we must also attend to embedding public policies with health for insurance (say, to guarantee pre-existing conditions and ban community rating) along with attending to those social determinants of health that underpin our overall well-being in areas that the health care system can’t address on its own.

Ultimately, we must move toward full-on health citizenship in America, restoring trust, and inspiring mutual respect for our fellow Americans. We have the perfect opportunity to do this with the tough learnings from a public health crisis that has attacked our bodies, our collective body politic, our minds, and our financial well-being.

My book, Health Citizenship: How a virus opened hearts and minds, went live on Amazon Kindle this week. Connect the dots between how the COVID-19 pandemic changed us as consumers, workers, students, home cooks, self-care patients, and even faith-based people — and how in the Great Lockdown, our minds, wallets, and bodies — personal and that entire body politic — have transformed in the public health crisis. This has ushered in the clear need for Americans to embrace full-on health citizenship in a new social contract for health, health care, privacy, and trust.

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a