Physicians in the U.S. are experiencing “death by 1,000 cuts,” according to the 2021 Medscape Physician Burnout & Suicide Report.

Medscape polled 12,339 physicians representing over 29 specialties between late August and early November 2020 to gauge their feelings about work and life in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic.

Medscape researched its first Physician Lifestyle Report in 2012. That research focused on physician “happiness” and work-life satisfaction.

Medscape researched its first Physician Lifestyle Report in 2012. That research focused on physician “happiness” and work-life satisfaction.

In 2013, the issue of burnout was called out on the cover of the report, shown here with the question, “does burnout affect lifestyle?”

In 2015, the Physician Lifestyle Report was titled, Health-Wealth-Weed Burnout.

By 2018, Medscape conducted a separate study from the Lifestyle report, titled the National Physician Burnout & Depression Report.

Then in 2019, Medscape added the word “suicide” to the title of the annual assessment.

For the descriptive, sobering title of the 2021 study, Medscape quoted one physician’s response who, when asked what is causing burnout and depression, replied, “It’s all of these causes; it’s death by 1,000 cuts.

In the second half of 2020, about 4 in 10 U.S. doctors felt burned out, with the specialties detailed here. This proportion of clinicians feeling burnout was roughly the same percentage as physicians who felt burnout before the pandemic emerged.

In terms of severity, nearly one-half of clinicians told Medscape that burnout had a “strong/severe impact” on their life, and another 1 in 4 said the burnout had a “moderate” impact on life.

Before the pandemic, 19% of physicians said they were somewhat or very unhappy in their work-life; after COVID-19, this rose to 34%.

The specialty-mix at the top-end of un-wellbeing shifted toward critical care, rheumatology, infectious disease, and pulmonary medicine which hadn’t featured as prominently in 2019/20.

Last year, urologists, neurologists, and nephrologists were the top 3 most burned-out specialists.

Many more women physicians than males felt burned out at a rate of 51% of women to 36% men.

And 8 in 10 doctors felt burnout before the start of COVID-19.

What factors contributed most to clinician burnout in this year’s survey? At the top of the list of stressors was the same issue hurting physician well-being last year: too many bureaucratic tasks, felt by 58% of the surveyed doctors. This issue has ranked high in the Medscape study for a while, exacerbated during the implementation of electronic health records and other administrative burdens like prior authorizations.

Following administrative hassles, working too many hours, lack of respect from staff and colleagues, and insufficient compensation and reimbursement are closely ranked in second place.

Together, we can classify these top burnout factors as time, money, and respect.

Note that “stress from treating COVID-19” was a key stressor for burnout cited 16% in terms of social distancing and societal issues, and COVID-19 stress from treating patients was cited by 8% of physicians.

Most physicians (69%) said they felt “colloquial depression” versus 20% who self-diagnosed with clinical depression — several depression lasting some time, not caused by a normal grief event.

How does that depression affect patient relationships? One in 3 doctors said they get easily exasperated with patients, and one-fourth report being less motivated to be careful with taking patient notes.

If there is good news here in the immediate moment, it’s that only 1% of physicians said they attempted suicide; but 13% has had thoughts of suicide.

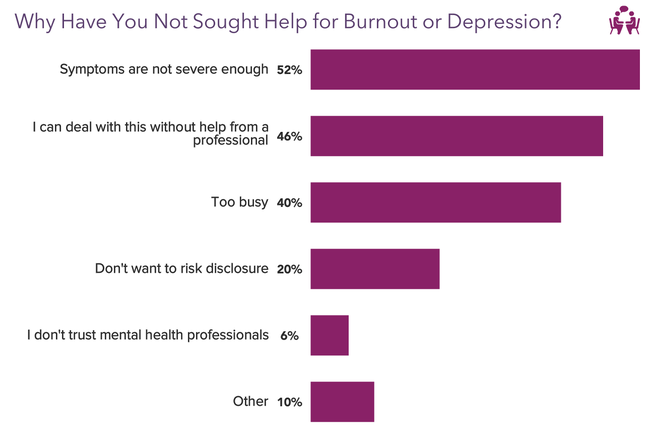

Most doctors have not sought help for burnout or depression because they either thought symptoms were not severe enough, or they could deal with the feelings without help from a professional.

But there may be stigmatization in seeking help.

And it’s also complicated in that only one-third of doctors reported their workplace offered a program to reduce stress or burnout.

FYI, here’s my last year’s 2020 take on the Medscape study: Physicians in America – Too Many Burned Out, Depressed, and Not Getting Support.

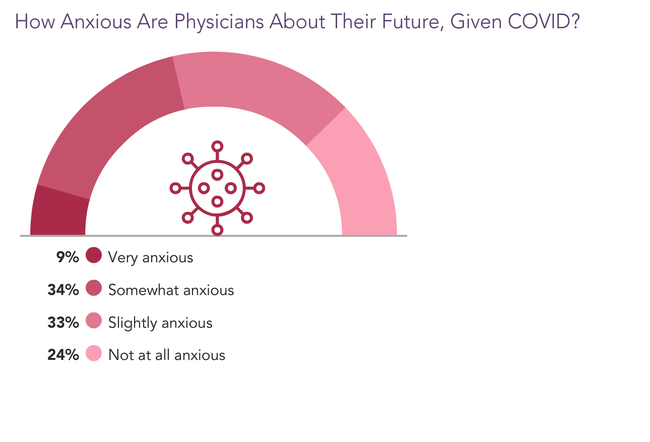

Health Populi’s Hot Points: In Medscape’s complementary report on Lifestyle & Happiness for 2021, physicians were asked how anxious they felt about their future in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, shown in the chart here from the report.

Four in ten U.S. doctors were somewhat or very anxious, and another one-third of physicians felt slightly anxious.

When the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the concept of the Triple Aim in 2007, it was founded on three pillars: enhancing patient experience, improving population health, and lowering per capita health care costs.

When the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the concept of the Triple Aim in 2007, it was founded on three pillars: enhancing patient experience, improving population health, and lowering per capita health care costs.

By 2014, Dr. Thomas Bodenheimer and Dr. Christine Sinsky called out a fourth aim — improving the work-life balance of clinicians and staff, re-coining the IHI’s concept as The “Quadruple” Aim with the fourth pillar of clinician well-being.

In their seminal article published in the Annals of Family Medicine. Bodenheimer and Sinsky wrote,

“Professional burnout is characterized by loss of enthusiasm for work, feelings of cynicism, and a low sense of personal accomplishment and is associated with early retirement, alcohol use, and suicidal ideation.”

In their anecdotes gathered through primary research, the authors quoted one doctor who would be cited in the 2021 Medscape survey on burnout:

“I am no longer a physician but the data manager, data entry clerk, and steno girl…I became a doctor to take care of patients. I have become the typist.”

Administrative burdens and hassles continue to rank top-of-mind in stressors driving physician burnout.

Add in the lengthening pandemic, growing variants of the virus, and supply constraints of inpatient settings in many health care markets, and this already-shaky pillar of the Quadruple Aim is weakened by the public health crisis.

As we consider re-investing in the U.S. health care system in the current discussions (and negotiations) of the American Rescue Act, part of the pandemic response must be targeted to medical providers at the front-line of COVID-19 care across several fronts: shoring up hospital finances is key, but ensuring the well-being of clinicians must be part of our Rescue strategy, as well.

Our clinicians’ well-being is not a future strategic forecast data point. This is a current threat to the quality and sustainability of health care in America for all patients in and beyond COVID-19.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for