Patients in the U.S. have been self-rationing medical care for many years, well before any of us knew what “PPE” meant or how to spell “coronavirus.”

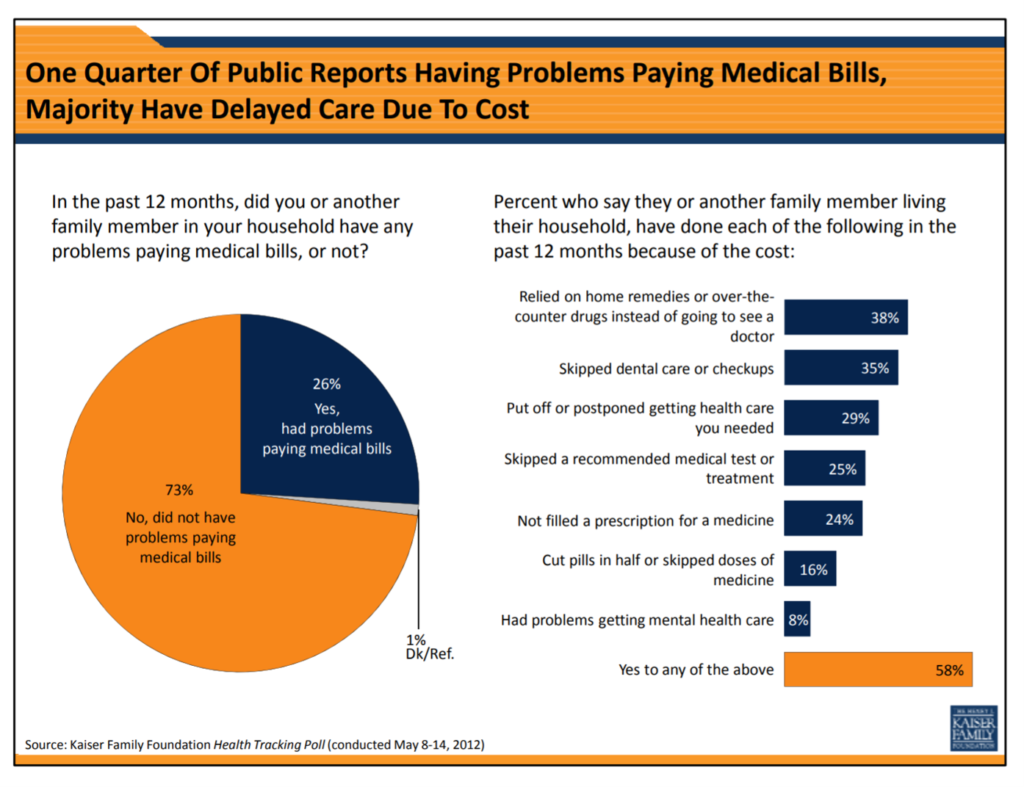

Nearly a decade ago, I cited the Kaiser Family Foundation Health Security Watch of May 2012 here in Health Populi. The first chart here shows that one in four U.S. adults had problems paying medical bills, largely delaying care due to cost for a visit or for prescription drugs.

Nearly a decade ago, I cited the Kaiser Family Foundation Health Security Watch of May 2012 here in Health Populi. The first chart here shows that one in four U.S. adults had problems paying medical bills, largely delaying care due to cost for a visit or for prescription drugs.

Fast-forward to 2020, a few months into the pandemic in the U.S.: PwC found consumers were delaying treatment for chronic conditions. In October 2020, The American Cancer Society explained that patients were postponing care, which also drove up peoples’ anxiety in dealing with their health and daily lives.

Several new studies converge to further tells us that Americans are self-rationing, delaying, or otherwise avoiding care nearly one year into the COVID-19 public health crisis.

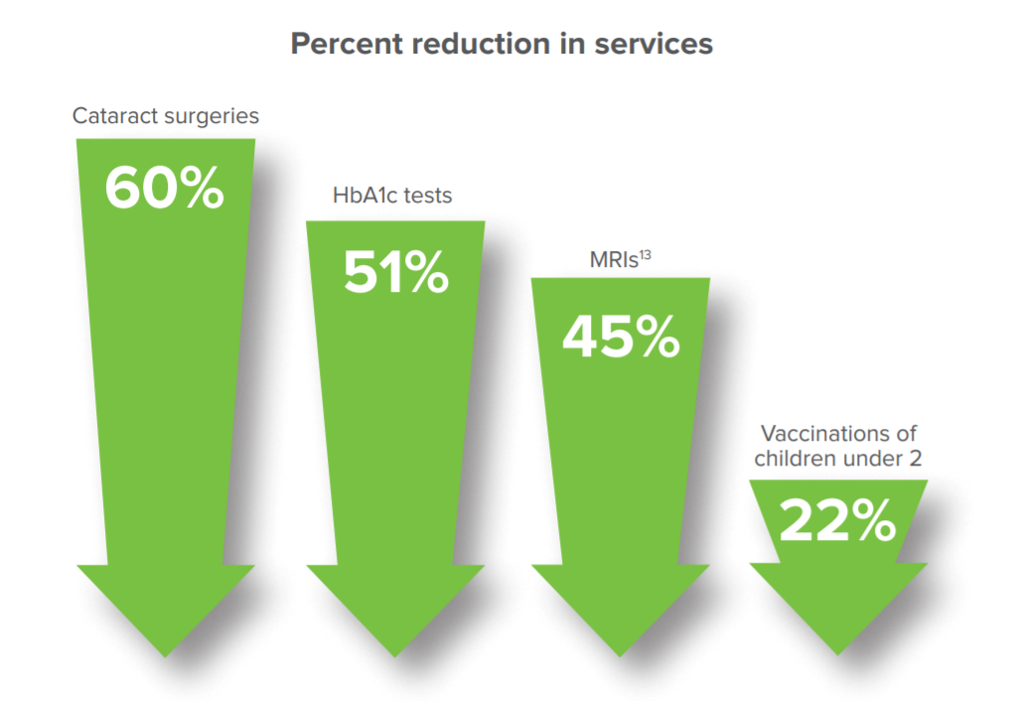

The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) partnered with Humana on a study to assess the pandemic’s impact on physician practices as patients avoided seeking medical care in the wake of the pandemic.

The study, No Time to Waste: Deferred Care and Pandemic Recovery, found that nearly 100% of doctors’ practices saw a drop in patient volumes by early April 2020, most of which were due to patients seeking safety avoiding exposure to the coronavirus.

The report synthesizes studies that documented patients avoiding seeking physician care, noting the phenomenon was “unlike anything the industry had seen:

The report synthesizes studies that documented patients avoiding seeking physician care, noting the phenomenon was “unlike anything the industry had seen:

- By June 30, 2020, 41% of U.S. adults delayed or avoided care based on a CDC report

- MGMA found physician productivity fell 45% in April versus the beginning of 2020, not rebounding much by July

- In May, only one-half of patients were interested in returning for an office visit with their primary care provider

- Larger practices have fared better than those with one to five physicians, possibly due to the bigger offices pivoting toward telehealth and remote health monitoring

- Patients return to pre-pandemic levels have lagged for certain specialties including pulmonology, otolaryngology, and cardiology.

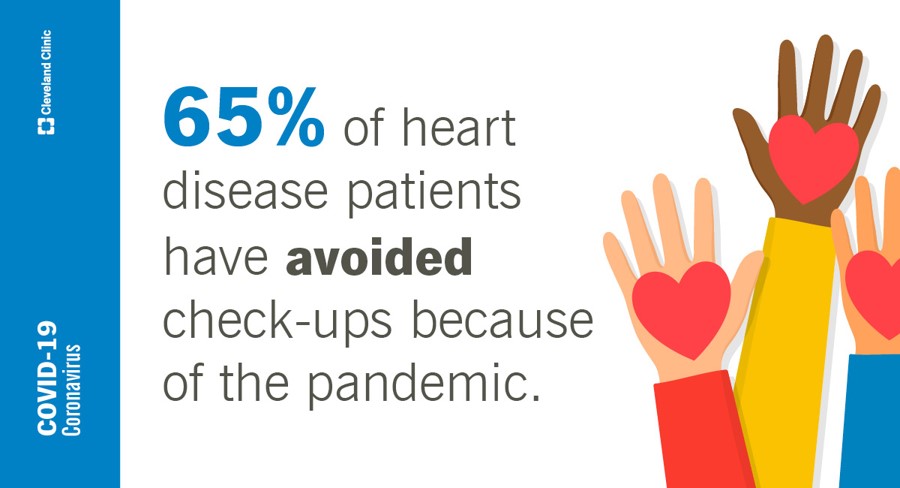

Speaking of cardiology, the Cleveland Clinic’s Heart, Vascular and Thoracic Institute looked into the pandemic’s impact on heart patients.

Their study found that one-half of Americans feeling heart symptoms have avoided seeking care for those concerns.

Furthermore, two-thirds of people already diagnosed with heart disease have avoided check-ups due to the pandemic. Worsening these patients’ wellbeing is that 47% of them report gaining weight during the pandemic, with 25% gaining over 20 pounds.

The Cleveland Clinic study did uncover some good news: some U.S. adults have adopted healthy habits over the past year, such as taking vitamins and supplements (35%), taking more exercise (32%), and eating a healthier diet (30%).

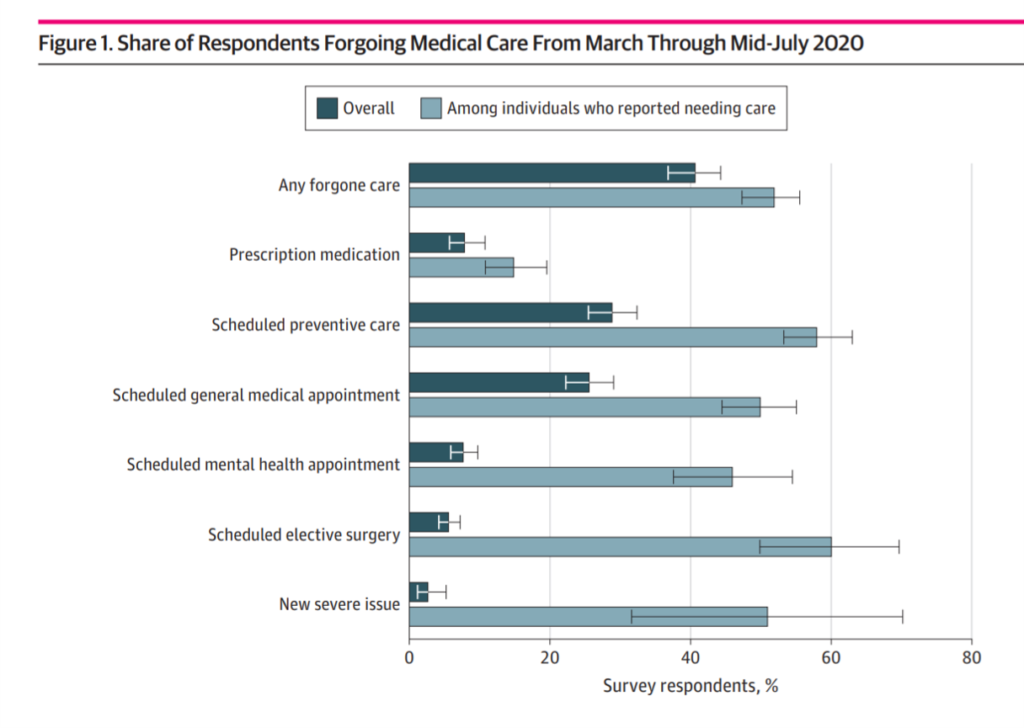

A JAMA Network Open study published January 21, 2021, looked into Reports of Forgone Medical Care Among US Adults During the Initial Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic.

The bar chart illustrates patients forgoing care between March and mid-July 2020 by reason: overall, four in ten patients avoided care, with over one-half reported needing that care. The most likely care avoided was scheduled surgery or preventive care, general appointments. Across all categories — note the mental health appointments avoided — a majority or large plurality of patients felt they needed to get that care.

The bar chart illustrates patients forgoing care between March and mid-July 2020 by reason: overall, four in ten patients avoided care, with over one-half reported needing that care. The most likely care avoided was scheduled surgery or preventive care, general appointments. Across all categories — note the mental health appointments avoided — a majority or large plurality of patients felt they needed to get that care.

The study found that patients’ avoidance of care fell into three categories: a practitioner’s office being closed, fear of exposure to the COVID-19 virus, or financial repercussions of the pandemic.

Financial concerns played into avoiding care for more patients dealing with missing doses of prescription medicines or missing schedule surgery.

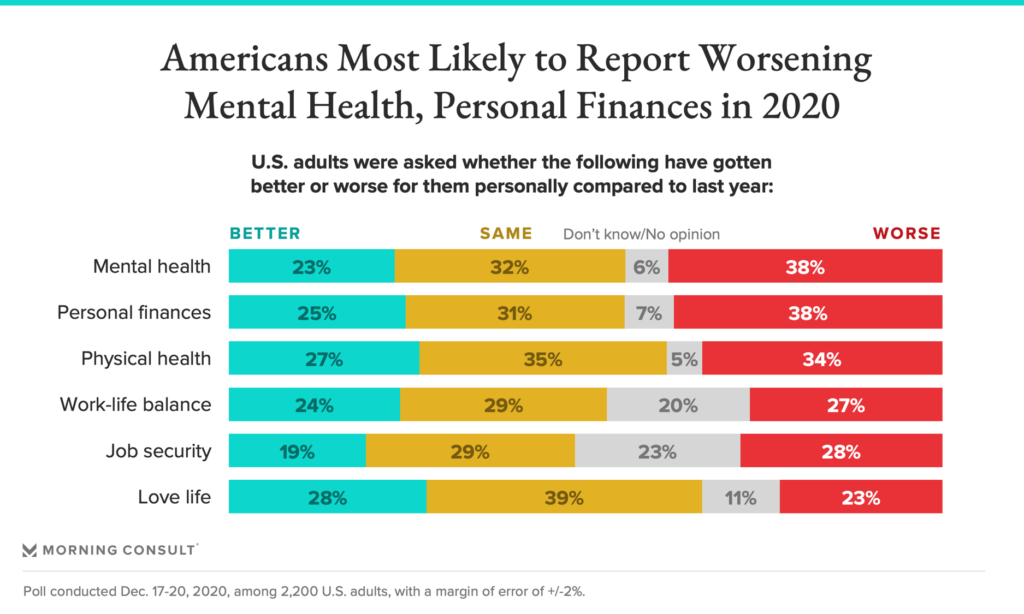

Health Populi’s Hot Points: By the end of December 2020, over one-third of Americans said their mental health, personal finances, and physical health had worsened over the past year, a Morning Consult poll found.

Another one in four people said their work-life balance, job security, and love life had fared worse, as well.

Another one in four people said their work-life balance, job security, and love life had fared worse, as well.

This study looked at more detail by demographics, learning that people the 11% of U.S. adults finding their lives got better in 2020 had postgraduate college degrees and earned over $100,000 a year.

Conversely, people who had less education earning lower incomes said lives and livelihoods got worse.

While income inequality was a feature of U.S. household economic lives before the pandemic, inequality has grown during the pandemic due to the growing chasm between “Main Street” and “Wall Street.”

The Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances found growing income disparity due to the disproportionate gains of the stock market, where people who save in 401(k) plans fared very well during the 2020 economy even during the public health crisis.

As we see to reimagine health and wealth in America post-pandemic, we must connect the dots in public policy between lives and livelihoods with the learning that COVID-19 worsened the lives of people who had lower incomes, less education, and unequal access to medical services and connectivity. The further adoption of telehealth and virtual care as a usual channel for medical services in an omni-channel approach to healthcare in our communities will help to ensure people have access to services post-pandemic. This, coupled with assuring health security for health citizens, can help to exacerbate the fiscal chasms worsening with the so-called “K-recovery” which has implications at the household and individual level for people needing and seeking health care.

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider

I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider  Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for